Back when he was a Peace Corps volunteer in Bolivia in the mid-to-late 1990s, Thaleon Tremain found himself wanting to help farmers, the kind of people who might grow coffee beans that could fetch a good price in a U.S. cafe — but not necessarily bring that profit back to the country of origin.

“Coffee, unlike most commodities, has incredible value to the retail customers,” Tremain says. “There’s a huge amount of value to coffee, so it has potential to have an enormous international development impact for people that are really poor. But the sad thing about it is so little of that money makes it back to the farmer.”

Tremain is CEO and co-founder of Pachamama Coffee, a cooperative founded in 2006 that’s owned by coffee producers in five countries: Nicaragua, Peru, Guatemala, Mexico and Ethiopia. The cooperative now operates three stores in the Sacramento area and a new, 4,100-square-foot roastery in El Dorado Hills. It’s an unusual business model: farmers own Pachamama, and Tremain and his cafe and roastery staff are employees paid by the cooperative.

From left, Carlos Reynoso, Merling Preza, Ed Alagozian, Thaleon

Tremain, Ruben Zuñega and Alejandro Gutierrez share

ribbon-cutting duties at the grand opening of Pachamama Coffee’s

El Dorado Hills roastery.

Tremain and some of Pachamama’s coffee producers, including Merling Preza of Nicaragua and Alejandro Gutierrez Zuniga of Mexico, participated in a ribbon cutting for the new roastery March 17. “I’m really proud and this is an honor to be here, just to see the work,” Zuniga says through an interpreter. “The scale that Pachamama has grown is directly going to impact our small-scale producers at origin.”

“Our business model is so unique,” says Preza, also via interpreter. She has been doing business with U.S. coffee concerns for 30 years, has been president of Pachamama since 2013, and is general manager of Prodecoop, a Nicaragua-based cooperative. “It’s the actual coffee producer that’s putting the coffee here, and they own the company.”

Pachamama pays farmers 70 cents a cup for coffee — much more than the 6 cents per cup they would get for conventional coffee or 9 cents for Fair Trade Certified. Still, it’s not necessarily an easy life for small-scale producers like Zuniga, who typically farm 2 hectares at 12 to 15 tons of coffee per hectare. “The small-scale producers have a harder time having a larger income,” Preza says.

A lot of people in the world qualify as small-scale coffee producers; according to Fairtrade International, 25 million smallholders produce 70-80 percent of the world’s coffee. In Nicaragua, a country known for its coffee agriculture, there are about 44,000 coffee producers, 97 percent of whom own 14 hectares or less, according to a 2017 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Cooperatives like the one Preza heads up have introduced more sustainable methods for these farmers to make a living. She says selling higher-quality coffee via the fair trade market allows farmers to invest back in their fields. It’s delicate work to cultivate specialty beans: The farms must be adapted to grow organic plants and the fertilizer must be all natural.

Nick Brown, a co-founder and advisor for the business who also served in the Peace Corps with Tremain, says he was interested in creating something that helped small-scale farmers earn a better living. “It was more about the people and the work rather than just the coffee,” Brown says.

The majority of the United States’ coffee shops are corporate offerings — in 2019, the market research firm Allegra found that 78 percent belong to Starbucks, Dunkin’ or JAB Holding Company (which owns Peet’s Coffee, Stumptown Coffee, Krispy Kreme Doughnuts and Einstein Bagels, among many other brands) — and the Capital Region is no outlier. “The real competition here is not the small, local guys,” Tremain says. “They’re publicly traded companies.”

The El Dorado Hills roastery has two 35-kilogram drum roasters,

able to each roast 40-50 pounds of coffee at a time.

Still, a fairly robust specialty coffee scene has developed in the Capital Region over the past two decades between well-established names like Chocolate Fish, Old Soul and Temple Coffee, as well as newcomers like Mast, Scorpio Coffee and Cora Coffee. (The author of this piece is a former Temple employee.)

Amid this landscape, Pachamama has sometimes seemed to fly a bit under the radar, its Midtown Sacramento roastery and cafe often less busy than others. “It’s a beautiful coffee town,” says Cruz Conrad, director of cafe operations for Pachamama, noting the wealth of local roasters in the area. “There’s a little bit of everything for everyone. We focus on farmer ownership and organic.”

The hope for the new El Dorado Hills roastery is that it can help Pachamama continue to grow. As opposed to the Midtown roastery, which has had just one 30-kilogram roaster in a tight space and has been at roasting capacity for about the last 2-3 years, the El Dorado Hills roastery has two 35-kilogram drum roasters in spacious confines, able to each roast 40-50 pounds of coffee at a time.

The higher volume is a boon for Pachamama, which roasts 800 pounds of raw coffee beans per day for a mix of cafe, wholesale and internet customers. “I want to push as much coffee as possible,” says Theo Bernados, head roaster at Pachamama. “The more volume we do, the more profits (the farmers) get.”

Additional profits are good for everyone, from the international farmer to the barista at one of Pachamama’s shops.

“I think having healthy farmers and well-compensated farmers and a healthy supply chain is good for everyone, including the people that work as baristas and roasters and workers in coffee.”

Thaleon Tremain, CEO and co-founder, Pachamama Coffee

“I think having healthy farmers and well-compensated farmers and a healthy supply chain is good for everyone, including the people that work as baristas and roasters and workers in coffee,” Tremain says. “What we really need is to make sure that our producers are sustainable, but not just in terms of environmental issues, but economically and socially sustainable.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Neighborhood Favorite: Konditorei Austrian Pastry Café

How a ballerina and a baker built a Viennese pastry shop in Davis

Anyone who has visited the coffee houses of Vienna will see the

resemblance between those venerable institutions and Konditorei

Austrian Pastry Café in Davis.

Bringing Together an ‘Experience’

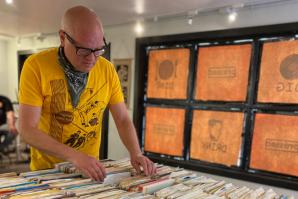

Pressed Record Cafe — a combination record store, coffee shop and supper club — finds its home in Sacramento

Pressed Record Cafe co-owners Dean Bardouka, Jon Blunck and James Williams have boldly chosen to specialize in three of Sacramento’s most populated business spaces.

How Cornish Pasties Got to California

Grass Valley’s Cornish pasties are a remnant of the town’s mining history

Cornish pasties are an edible trace of the gold rush, connecting

Grass Valley to a global history of migration and

extraction.

Getting to Know: Vanessa Maggio

The co-owner of All Good and Official Brand strikes out in the plant-based snack market

Vanessa Maggio, vegan snack enthusiast, is the owner of Gxxd

Box, an upcycled shipping container that will soon be

situated somewhere within Midtown Sacramento.

Main Street: At Steady Eddy’s, More Than a Hill of Beans

The coffee house and roasting room continues to be a fixture in thriving downtown Winters

After taking over the historic Steady Eddy’s in 2013, owners Jamell and Carla Wroten are focused on expanding the wholesale business.