When you think about the building of the transcontinental railroad, you’ll probably remember history lessons of the grueling work done by the more than 21,000 workers who had to blast through mountain passes and build the railroad by hand. You wouldn’t know that a tragic love story led to the railroad that connected the East and West coasts for the first time. It was the real life story of Theodore and Anna Judah, a devoted couple in the 1800s whose marriage was also a soulmate-match that outlived Theodore’s early, untimely death.

It was caused by yellow fever, sparked by a mosquito bite he endured when the couple stopped off in Panama (before the canal was built) on their way to New York City. They were seeking funds from tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt to build the transcontinental railroad — which, ironically and fatefully, would one day eliminate the necessity to even travel from coast to coast by ship.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Theodore Dehone Judah (1826-1863) was a highly regarded civil engineer and geographical surveyor whose site location efforts led to the first cross-country railroad in the United States — which he didn’t live to see. Yet it was his wife Anna’s paintings and flower pressings that helped convince a Civil War-weary Congress, as well as skeptical millionaires, to make nation-spanning travel a bit more comfortable than wagon trains and seemingly eternal steamship treks around the treacherous Cape Horn or through the aforementioned Panama shortcut.

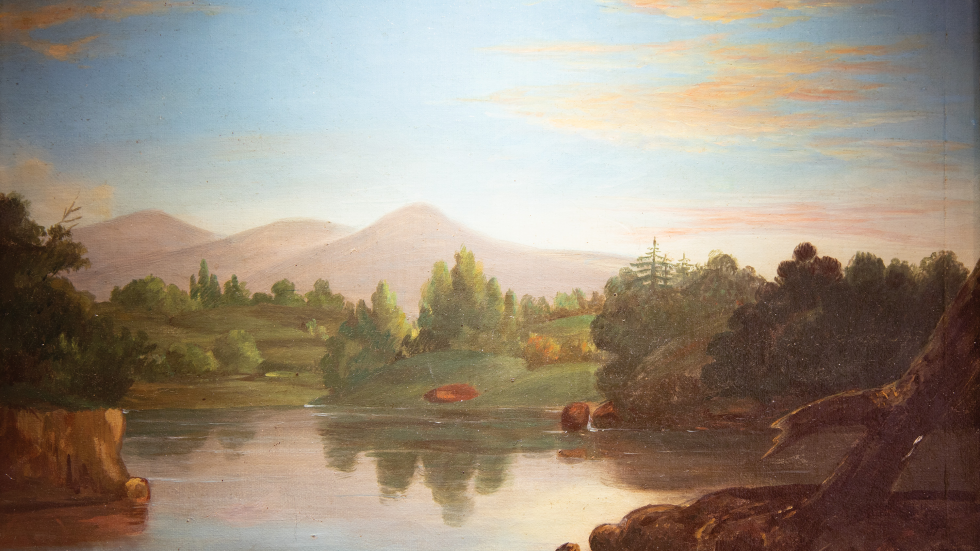

Anna Judah made oil and watercolor paintings of the Sierra Nevada

mountain landscape that helped show investors the site of the

soon-to-be-built transcontinental railroad which would connect

the East and West.

Judah bemoaned the fact that to traverse the United States “could take three-to-four months by ship or six months by wagon train. He dreamed of connecting the country” — by laying out a route of tracks that would travel over land, including the seemingly improbable (and possibly unpassable) Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Christine Pifer-Foote, a retired schoolteacher and ordained minister, has made it her mission as a volunteer docent and guest curator at the California State Railroad Museum to not only give Anna Judah her due, but also to elevate her to superhero status in the universe of neglected historic heroes, female division.

The evidence is all there — in loving letters to her husband, and in the naturalistic paintings she did both in oil and watercolor, which Theodore used as exhibits for his funding-pitch presentations to elected officials and millionaires, including Collis P. Huntington, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker, who controlled the Central Pacific Railroad.

Since there were no picture-postcards back then and only rudimentary, black-and-white forms of photography, Theodore had to pitch the powers-that-be with engineering schematics and maps, hardly the stuff of travel brochures. So he wisely decided to invite Anna to pack up her canvases, oils, paintbrushes and a side saddle to join him on his location scouting trips, according to Pifer-Foote. “Side saddles were what women used in those days to maintain their modesty by not having to straddle the horses they rode while wearing skirts,” she explains.

“The sketches, herbariums and various bits I did were taken by (Theodore) to Washington,” Anna Judah wrote in an 1889 letter to the periodical Themis. She said that once there, her work was “tacked above the points they represented on his maps and profiles. Senators and representatives in Congress were eager to know and hear all he could tell and show them of his survey and his gigantic work.”

While appreciated in her youth for her artistic talent, Anna Judah (1828-1895) might have seemed an unlikely choice for the role of adventurer (or adventuress).

Born into a life of privilege — her father was John J. Pierce, from a notable Greenfield, Massachusetts family — Anna Ferona Pierce attended the Miss Draper boarding school in Connecticut, where she studied sketching and botany. As it happened, these comprised the skill set she brought to documenting her travels with Theodore. As for her husband, she had met and fallen in love with him when she was 19 and he was 21; he was working as a surveyor in Greenfield for the Connecticut River Railroad. “He was very handsome,” Pifer-Foote says, “and he ended up writing her the most beautiful notes.”

Theodore’s connection to Sacramento, where he has a school named for him (see sidebar), arises from when he worked for the Sacramento Valley Railroad, while quietly envisioning a transcontinental train route. Because he was lobbying the electeds in Washington, D.C., to not only hear but also finance his dream, he made numerous (and arduous) trips to the nation’s capital. By this time, he was married to Anna, who accompanied him on his treks and handled all the paperwork for their passages and his presentations.

“Anna shared his dream,” says Pifer-Foote, “but more as an equal partner than as an assistant. This was, from everything I’ve learned in my research, a marriage of true equals.”

After her husband’s death, Pifer-Foote writes in her museum exhibit, “The grieving Anna accompanied his body back to Greenfield. The last leg of their train ride, Springfield to Greenfield, was on the Connecticut River Railroad, the same railroad that Theodore helped build.”

Do you know of any unique history, events, people or places for us to share in The Back Story? Email us at editorial@comstocksmag.com.

Recommended For You

Anna Judah: Far More Than Theodore Judah’s Victorian Housewife

Through her artistry, she brought the transcontinental railroad to life — before it was built

You wouldn’t know that a tragic love story led to the railroad that connected the East and West coasts for the first time.

Whatever Became of the Auburn Dam?

One of the largest flood control projects in the country was never built

The Auburn Dam could well be the most talked about water storage and flood control facility in the country that simply doesn’t exist — no matter how much it’s been argued about, advocated for and against, legislatively proposed and architecturally rendered.

The Back Story: That Other Time We Had a Local Baseball Team

The Sacramento Solons still evoke fond (and funny) memories

As a team, the Solons had more stops and starts in the area than light rail at rush hour. There were iterations of the club in 1903 and 1905, from 1909 to 1914, from 1918 to 1960, and finally, from 1974 to 1976.

The Back Story: The Rocket Company that Roared

Aerojet was once a major player in the region — until it wasn’t

If you’re ever on Jeopardy and you’re asked to name an American company that not only helped the country and its allies win a war (the Big One) and, a bit more than two decades later, helped send it to the moon — before getting mired in a sludge of litigation — remember one of this region’s more complicated and often controversial sagas: Aerojet.

The Back Story: McGeorge School of Law

The truth and folklore behind Sacramento’s biggest law school

Prof. Michael Hunter Schwartz recounts stories about some big names that passed through McGeorge School of Law.

The Back Story: The Long Pour

After 124 years in business, Frasinetti Winery continues making and serving its wine

Frasinetti Winery is the oldest family-owned wine producer in the

Sacramento Valley, withstanding the Prohibition and both World

Wars.