The Auburn Dam could well be the most talked about water storage and flood control facility in the country that simply doesn’t exist — no matter how much it’s been argued about, advocated for and against, legislatively proposed and architecturally rendered.

Dreamed of for decades, and having prompted scores of editorials — as well as a new (and excellent) documentary, “The Dam That Never Was,” by writer-director Steve Hubbard — it still doesn’t exist.

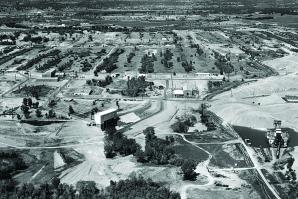

At first, the Auburn Dam sounded like a good idea when it was suggested almost 70 years ago; preliminary construction began a decade later. It would be a concrete weir almost 700 feet high on the American River’s north fork, bordered by two counties: Sacramento and El Dorado. Intended to be built by the United States Bureau of Reclamation as a component of its enormous Central Valley project and to be open for business about a half-century ago, it would have stored more than 2 million acre-feet of water, regulated the flow of river water and, as one of the tallest dams in the country, been a highly visible, even iconic model of flood control.

“There was significant political will among local, regional and congressional elected officials to build the project,” says water policy expert Ane (pronounced “Annie”) Deister, executive director of the statewide nonprofit Urban Water Institute since 2017 and a member of its board of directors for nearly three decades. “But because of the location, being an onstream project, the environmental impacts were significant. The recreation industry in the area had been established for a long time, and the environmental and recreational business coalitions voiced major concerns.

“Another consideration,” she continues, “is that the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation was the project sponsor” — meaning the federal government would be the owner and operator. “But a major impediment was the discovery of a fault line that would have had serious consequences due to the likelihood of an earthquake.” After earthquake retrofits were factored in, Deister says, “The project did not appear to pencil out.”

Deister has a first-hand knowledge of the ebb and flow of water and budgets. In addition to her current post, she was general manager of Placerville-based El Dorado Irrigation District and was in a top leadership post at the fabled — and feared for its geographical and political influence — Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (the agency Robert Towne thinly disguised in his screenplay for the film classic “Chinatown”).

Meanwhile, Lincoln resident Steve Hubbard used some of his Silicon Valley retirement time and money to finance the aforementioned film, “The Dam That Never Was.” While even-handed, the straightforward documentary — which Hubbard produced, directed, wrote and narrated, aided by students in his Sierra College filmmaking course — makes it clear that the dam that wasn’t built never should have been from the get-go.

“Its location was always problematic,” he says, “which early (19th-century) inhabitants of California recognized. They knew flooding would always be a risk unless the dam was properly sited.”

Even so, Hubbard adds that when he started researching his film, “I could ask six different people in Auburn why they thought the thing shouldn’t be built and come away with six different answers.” Those included earthquake fears — two years after a magnitude 5.9 earthquake in 1975 near Oroville Dam, preliminary construction came to a dead stop, even though that dam is about 50 miles away from where the Auburn Dam was being situated — as well as stratospheric costs (more than $6 billion) which could be recovered only minimally, such as by selling hydroelectric power generated by the water. Other reasons given for the Auburn interruptus was the disruption or downright destruction of habitat, such as spawning salmon, by altering the basic functions of the river.

For years, a pro-construction lobbying group called the Auburn Dam Council met regularly in the hope of reviving interest in the project. When it began in 1959, it was led by Bill Cassidy, then-publisher of the Auburn Journal. Multiple efforts to reach it or its members were futile and its phone number has been disconnected.

Ane Deister, executive director of the Urban Water Institute,

said local and regional officials wanted to build the Auburn Dam,

but the environmental impacts were too significant.

Asked if she thinks any dam could ever be built in California, much less Auburn, despite the demonstrated flood-control need, Ane Deister remains optimistic.

“Interestingly, the Sites Reservoir Project, being designed in Northern California about 10 miles west of the town of Maxwell (in rural Glenn and Colusa counties) has a good chance of being built,” she says. “The Sites Project Authority describes the project as a generational opportunity to construct a multi-benefit water storage project that helps restore water operations and supply flexibility.”

In November, the Bureau of Reclamation and Sites Project Authority moved ahead on the Sites Reservoir Project. Sites would be the second largest off-stream reservoir in the nation and would increase Northern California’s water storage capacity by up to 15 percent.

“The unique feature is that Sites is not a traditional reservoir project, located adjacent to a water source,” she continues. “It’s an off-stream facility, designed to capture stormwater flows in the Sacramento River, after all other water rights and environmental regulatory requirements have been met.” She says the project is being designed “with climate change resiliency,” adding that “supporters and users include both urban and agricultural agencies. That is a big deal. They have money and support from the California Department of Water Resources and Congress, as well as many would-be water users throughout the state.”

–

Do you know of any unique history, events, people or places for us to share in The Back Story? Email us at editorial@comstocksmag.com.

Recommended For You

The Back Story: That Other Time We Had a Local Baseball Team

The Sacramento Solons still evoke fond (and funny) memories

As a team, the Solons had more stops and starts in the area than light rail at rush hour. There were iterations of the club in 1903 and 1905, from 1909 to 1914, from 1918 to 1960, and finally, from 1974 to 1976.

The Back Story: The Rocket Company that Roared

Aerojet was once a major player in the region — until it wasn’t

If you’re ever on Jeopardy and you’re asked to name an American company that not only helped the country and its allies win a war (the Big One) and, a bit more than two decades later, helped send it to the moon — before getting mired in a sludge of litigation — remember one of this region’s more complicated and often controversial sagas: Aerojet.

The Back Story: McGeorge School of Law

The truth and folklore behind Sacramento’s biggest law school

Prof. Michael Hunter Schwartz recounts stories about some big names that passed through McGeorge School of Law.

The Back Story: The Long Pour

After 124 years in business, Frasinetti Winery continues making and serving its wine

Frasinetti Winery is the oldest family-owned wine producer in the

Sacramento Valley, withstanding the Prohibition and both World

Wars.