Estella Sanchez had just sold her car to pay rent on Sol Collective when she started to contemplate how she might buy the building. It was the late 2000s and she was working three jobs and pooling resources from a coterie of members to run the art center. Paying rent on the downtown space had begun to feel futile, a potential dead end since rising rents were leading neighboring galleries to shutter.

Sol Collective Founder Estella Sanchez says conversations around

ownership in the arts have been around “forever.” She thinks

there is more urgency now because the real estate market is

rising quickly.

“We had access to so many different folks in the community with different skill sets,” she says. “There were a lot of different ways of working towards keeping the place going; we had to just always be creative.” Community investment was proof the center was essential, but it wasn’t a tenable long-term solution.

Around the same time, Unseen Heroes co-founders Roshaun Davis and Maritza Davis were curating well-attended creative events like Good Design Market, which invigorated the economically depressed neighborhood of Del Paso Heights. Unseen Heroes spent the 2010s producing successful community-building events like Gather Oak Park, which on a given night generated $3.5 million in revenue. But the company was sometimes priced out of rented buildings or worse, pushed out with a landlord seeking to recreate and capitalize on its concepts.

Some members of the arts sector attribute their instability to a lack of ownership in the creative movements they build. A year out from pandemic reopenings, city and state programs are supporting artists in unprecedented ways — but the relief is temporary. Davis posits that only when creatives own their spaces and gain other forms of equity will the region “build a better and sustainable economy, a sustainable vibrancy.”

Other U.S. cities have shown it can be done, often with government and institutional support. Austin, Texas, in addition to having a thriving arts scene that acts as an economic engine, is consistently ranked one of the best cities for artists. On the world stage, Germany’s cultural life has benefited from governmental and private support of the arts, engendering a culture of patronage from public audiences. But for many cities, the marriage between culture and city planning has proven elusive. Since the 1980s, U.S. interest in merging the arts and urban planning has waxed and waned. At this moment of reckoning in Sacramento, conversations are taking place that could lead to urban development that benefits both artists and the city as a whole.

Worthy of investment

In fall 2022, Verge Center for the Arts brought back its monthly art salon series, which invites artists to gather and discuss assigned readings related to art criticism. The idea, says the center’s founding director Liv Moe, is to encourage artists to “stay up on different ideas and meaty subjects.”

A recent meeting devolved into an angsty, ad-hoc brainstorm session over how to generate more attention for Sacramento artists. Where were the patrons, lamented the artists, situated around a giant pizza box. Friends and family were appreciated supporters, but why wasn’t there a wider breadth of visitors at their shows? Sacramento was home to incredible artists, but how were they expected to stay in a city where the galleries were a revolving door of openings and closings?

“There’s never quite enough infrastructure here between institutions and venues and the kinds of things that make it possible for you to have an art career to stay here.”

Liv Moe, founding director, Verge Center for the Arts

Moe validates the collective’s concerns, pointing to Sacramento’s nonexistent arts and culture budget. With the exception of the Percent for Art policy, Sacramento’s arts sector only receives funds on a case-by-case basis as an augmentation to the approved budget. “That is something that makes me really crazy, because I think all of the aspiring that sometimes happens here in terms of our city leaders and policymakers, the cities they often point to as being so vibrant and that they want to emulate are places that have budgets in their city budgets for arts and culture. So it’s not, like, an ostentatious, crazy thing to do.”

Plenty of cool arts events take place independent of policymakers. Sacramentans still speak fondly of 2016’s Art Hotel, the temporary exhibition organized by the nonprofit M5Arts that transformed every inch of a five-story abandoned hotel in downtown Sacramento with conceptual art. In 2022, patrons were inspired by artists’ DIY spirit once again with Coordinates, a labyrinthine gallery developed by curator Faith J. McKinnie that featured the work of 35 Sacramento-area artists.

Journeying from room to room of the soon-to-be-demolished building (a former news broadcast headquarters) near the R Street Corridor, visitors were immersed in an avant garde dinner display by one turn and in a spectral space full of flowy fabric by another. In her curator’s statement, McKinnie asserted the space was “further evidence that Sacramento’s creative community is worthy of investment.”

“If we want this city to have a vibrant ecosystem where art is created and experienced, it’s really important to have the spaces secured where young people can go and see art, learn about art and have the opportunity to envision themselves and that career field.”

Estella Sanchez, founder, Sol Collective

These temporary DIY galleries, plus Sacramento’s abundant warm weather block parties, raise the city’s cultural quotient, but they don’t solve the knottier issue of talent retention. Most graduates of UC Davis’ MFA program make a hurried exodus to the Bay Area upon the program’s completion, and many artists, like the experimental artist Skinner, end up making the same decision even if they do attempt a career in Sacramento.

“There’s never quite enough infrastructure here between institutions and venues and the kinds of things that make it possible for you to have an art career to stay here,” says Moe, an interdisciplinary artist herself. “So anytime there’s a curator or an artist or somebody I think is doing amazing work, I know there’s probably going to be a sunset by which time they’re going to want to go to a place that has more opportunities.”

Liv Moe, founding director for Verge Center for the Arts, says

ownership is essential for long-term arts models, and that if

Verge didn’t own its building, the organization would not

survive.

The doom and gloom is not without a bright spot. In March 2022, Mayor Darrell Steinberg approved an investment of $10 million in Sacramento’s creative economy to countervail the pandemic’s impact on artists. As cynical as the cultural community gets, Moe concedes, Sacramento’s $10 million investment is “huge.” The director adds she’s grateful for the work of Megan Van Voorhis, who the City of Sacramento brought on as cultural and creative economy manager in fall of 2020. Van Voorhis spent nearly two decades strengthening arts and culture for Arts Cleveland; now, she’s aggressively building programs and going after pots of money on behalf of Sacramento’s creative class.

Van Voorhis estimates that collectively — between the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act grants for the creative economy, tourism and art education, plus the allocation to arts through the American Rescue Plan Act — her department’s COVID recovery funds have totaled $30 million. “I think it’s important to think about that, that’s even outside of $2.6 million in investments that we received for the FY22 year that ended in June,” she says. “That’s an expression of the city’s value.”

Another program coming online in 2023 is the California Creative Corps program, the state legislature’s effort to increase public awareness related to water and energy conservation and climate mitigation. Out of the program’s $60 million, the City of Sacramento’s Office of Arts and Culture received $4.75 million, the highest award amount possible for a single organization from the program. “When you get that momentum, that’s something that you can kind of build from,” says Van Voorhis. Additionally, crowdfund matching programs like In Our Backyard help to support the grassroots efforts for which Sacramento’s arts community is known.

Ownership as empowerment

Roshaun Davis of Unseen Heroes has evolved the way he builds up Sacramento’s creative industry. He says pausing during the pandemic to evaluate Unseen Heroes’ pipeline issues illuminated for him “the value of creativity.” Working with an impact investor helped him move toward the goal of owning an arts venue. If artists continue to depend on rented spaces, he says, “We will continue to be displaced, because we don’t own.”

Davis is currently looking to purchase a building to house CLTRE, his new community development nonprofit. He plans to revitalize the building both by renovating it and filling it with local entrepreneurs. (The name is a backronym that Davis is still working to define; he’s considering “community-led transformative real estate” or “creating leverage to ready entrepreneurs.”)

Comstock’s photographed Curator Faith J. McKinnie in her

eponymous gallery in 2021. She operated her gallery for less than

a year before the building owner tore it down to create more

space for apartment housing.

A leveling of power could start with landowners tapping artists to fill their spaces at a discount, or even for free. “There’s a disconnect where they would rather sit on land until someone can afford the space,” she says, citing the empty buildings on K Street.

Ten years after opening Sol Collective, Sanchez owns the building. She credits her entrepreneurial spirit to being the child of immigrants. She also found an ally in Brian Fisher, the owner of Sol Collective’s adjacent building, who would go with her to speak to bankers. “It was really helpful to have a white male speak on our behalf to other white males in the bank industry to say, here’s the financial situation,” she says. “It’s important for people to understand that as a woman, it’s harder to go in and get taken seriously. And then as a woman of color, there’s another layer.”

Established in 2005, Sol Collective is dedicated to art, culture,

activism, and the integration of wellness and the arts.

Owning the building has allowed Sanchez and team to live out their long-term vision of stewarding diverse representation in art. They now have the opportunity to root down and develop the space upwards for subsidized artist housing and cooperative spaces. “If we want this city to have a vibrant ecosystem where art is created and experienced, it’s really important to have the spaces secured where young people can go and see art, learn about art and have the opportunity to envision themselves and that career field,” she says.

Much-needed exposure

Media coverage rounds out a healthy diet for artists’ success. At the moment, local arts journalism is undernourished. Submerge, the biweekly arts magazine that ran for 12 years, is on a seemingly permanent hiatus due to the pandemic. The alternative weekly Sacramento News & Review, a free and once-ubiquitous publication known for its arts-heavy calendar and accessibility, ceased printing back in 2020, although it still runs online. The Sacramento Bee, too, runs arts stories in a limited capacity these days, without a resident arts editor.

“I always tell artists, you can create 1,000 pieces in one year, but if no one’s talking about it, it almost feels ephemeral,” says McKinnie. As part of her role as a critic and curator, she helps artists sell and advertise their work, to frame and position it for consumption. “I think it’s important because someone in SF reading about a show here, knowing nothing about the scene but reading it, could make the trip after what they read. I’ve done it all the time,” she says.

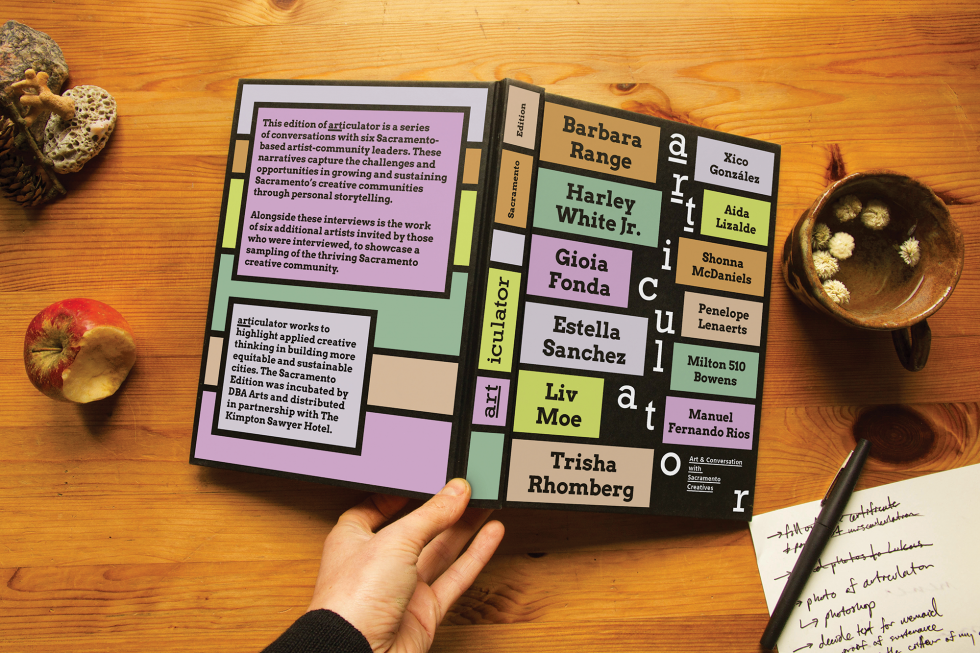

Bill Stotler, a senior business strategist with experience in urban planning and community development in the Bay Area, recognized Sacramento’s need for an arts publication. In 2018 he created a zine called Articulator to highlight city artists and attract visitors to their galleries and studios. “One of the goals is I wanted to get people staying downtown at DOCO out to Oak Park, over to R Street,” he says.

Articulator highlights Sacramento artists in its 2021 book and

encourages conversation between artists and urban planners

through its speaker series. (Photo courtesy of Articulator)

After making connections with Visit Sacramento CEO Mike Testa and the Sacramento Hotel Association, Stotler got Articulator placed in hotels. Last year he produced Articulator into a big, beautiful book spotlighting a dozen artists’ first-person narratives along with color photographs of their work and studio spaces. Beyond the paper product, Stotler wants to facilitate face-to-face discourse that’s productive toward the values within its pages. With Articulator’s “Art Shapes Cities” speaker series, voices from the book and beyond come together with urban planners to seek progress.

At Articulator’s recent “Art Shapes Cities” speaker series, Megan

Van Voorhis moderated a conversation with arts leaders to discuss

ideas of ownership and revitalization strategies for Sacramento.

(Photo courtesy of Articulator)

A recent installment of the series featured a panel of four female arts leaders, including Sanchez of Sol Collective. As one of the only panelists who owned her building, Sanchez was hopeful for a more community-centric market dynamic. “I’ve been learning a lot about this world,” she said of her forays into property ownership. “That’s the direction some of us are going into; (we’re) trying to figure out how we can do that.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Getting to Know: Faith J. McKinnie

Gallerist Faith J. McKinnie is highlighting the work she wants to

see in her Midtown gallery that highlights contemporary art

by underrepresented artists.

Art Exposed: Estella Sanchez

It’s been 12 years since Estella Sanchez signed rent papers on the first Sol Collective Arts and Cultural Center in Del Paso Heights. More than a decade, hundreds of art exhibitions and thousands of community events later, Sol Collective recently purchased the building on 21st Street in Sacramento. We sat down with Sanchez to talk art, activism, the importance of building ownership and snacks.

Art Exposed: Gioia Fonda

How an artist and Sacramento City College professor teaches imagination

Gioia Fonda, an artist and professor at Sacramento City

College since 2006, takes every opportunity to combine art with

teaching.

Getting to Know: Miranda Culp and Laurelin Gilmore

The owners of Amatoria Fine Art Books in Sacramento share a deep love of books

Miranda Culp and Laurelin Gilmore are accustomed to the look of

wonder on the faces of the people who stumble into their

independent bookshop, Amatoria Fine Art Books.

Getting to Know: Makers Mart

The production team behind a long-running holiday fair hits its stride with city funding and community support

The team behind Makers Mart, Sacramento’s annual holiday bazaar, has dealt with a litany of challenging logistics over the last decade. But the show always goes on in high style.

Art Exposed: Vincent Pacheco

A graphic artist blurs art and design and plays with the cultural language of piñatas

The artist builds piñatas in various forms of cultural artifacts. Each is a temporary monument to family, identity and cultural heritage.

Room at the Top

Many nonprofits in the Capital Region are headed by women

Statistics and personal stories suggest that, overall, women may find more growth opportunities at nonprofits, and as a result, many more are opting for this route.