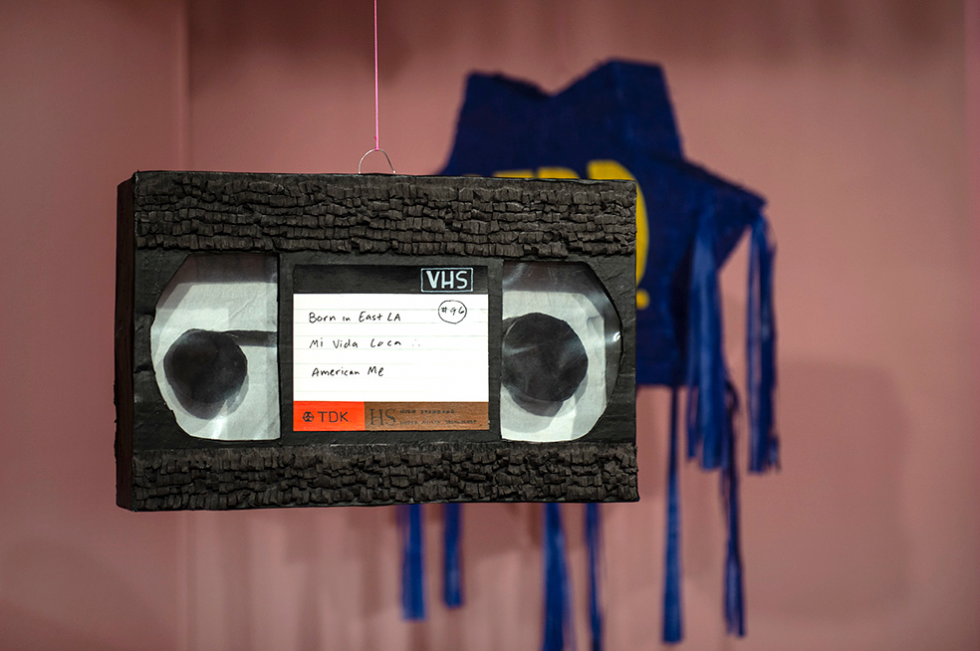

Devoid of people, the installation shots of Vincent Pacheco’s immersive 2020 installation Smile Now, Cry Later hit home hard. The installation featured a dozen or so piñatas, one in the shape of a San Francisco Giants baseball cap, another as the likeness of a food truck, and another yet of a one hundred dollar bill, all soundtracked by classic songs in an empty, rose-tinged room at The Garage on The Grove. Reflecting a moment in Sacramento’s history when a global pandemic emptied streets and shuttered cultural venues, the poignancy of Pacheco’s lonely piñatas cannot be easily forgotten.

Taken by local artist and photographer Muzi Li Rowe, the installation images are Candida Höfer-esque — introspective and reflective. Capturing mood and atmosphere, as well as the harmony of the arrangement of deeply personal investigations into cultural identity, these images perform as works of art themselves and proffer an intriguing curatorial concept: an exhibition about the images of another exhibition (arguably a conceptual nod to the work of artist Leslie Hewitt). Despite the power of Rowe’s images, it’s the presence of the piñatas that lend the scenes real gravitas.

Pacheco’s piñata series “Smile Now, Cry Later” ran at Garage at

the Grove in 2020.

The piñatas resonate deeply when considered against the ways in which the pandemic ruptured family connection and disrupted social interaction. When viewed contextually, it is difficult not to wonder about the people behind a giant knuckle duster, VHS tape and tequila bottle, and the relationships at play among them. Pacheco, a graphic designer, illustrator, educator and artist who lives in the Tahoe National Forest, considers his piñatas temporary monuments to family, identity and cultural heritage.

Pacheco’s larger-than-life piñatas “combine a range of stories

and memories,” he says.

Following a recent presentation of new work in the piñata series “Sup Foo” at Axis Gallery — located alongside Verge Center for the Arts on S Street in downtown Sacramento — Pacheco delves into the nitty-gritty of his varied practice. He discusses his experience living and working in the Tahoe National Forest, time spent in residence at Mass MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts, and where he is headed next, with or without his symbolic floating vessels.

With his “Sup Foo” piñata series, Pacheco utilized many

materials: cardboard, plastic, glue, aluminum, styrofoam, moss,

shoe laces, a ziploc bag, acrylic and ink. The installation ran

in December at Axis Gallery.

I want to begin with “Smile Now, Cry Later” and your piñatas. What prompted this body of work and how does it connect to your larger practice?

“Smile Now, Cry Later” was a new area of investigation for me; a pivot inward. My work up until that point was focused on art as experience and using the tactility of daily life as material for the work. I explored the concept of nowness, becoming one with all things. It was very Buddhist I guess you could say, but there was always something missing from the work — something I was ignoring.

I come from a family of Mexican drug dealers, gang bangers and outlaws from San Francisco’s Mission District. Criminal behavior has been a perennial feature in my life, and while I managed to avoid that life of crime, my family has been entrenched in it for generations. Despite being the outlier, I have always carried their stories with me, along with the trauma and the anger. I tried my best to ignore it over the years, to move beyond it and to become a better version of my family.

I became an upstanding citizen, a taxpayer, a college professor. I thought my progress in white society would advance us and somehow erase our troubled history. It never worked, though, and when the pandemic hit, I realized that if I was to ever make true spiritual progress in life — or in my work — I had to confront my family’s history head on — to sift through it, and to uncover my place within it. Ignoring it was no longer a viable option.

A function of piñatas is that they are created to be destroyed in celebration. With your repositioning of them as art objects, this function is problematized: are they meant to be kept or used as historically intended? How do you view their function and their philosophical role?

I wasn’t expecting the response I got from fellow Mexican Americans who saw the show. For many, the symbols and iconography I presented spoke to shared minority experience. Despite each piece being highly personal, there was a universal quality to the work that became a point of pride for those in the Chicano community at the opening. The functional nature of the piñatas is something I haven’t yet resolved because of this.

The work ultimately shed light on an underrepresented group of people, and I do feel some obligation to preserve the work somehow. Voices like mine are rarely given a platform in contemporary society, and these are indeed art objects and sculptures that have value. However, if I don’t destroy the piñatas with a baseball bat as intended, do I prevent activation of the work? Is the act of destruction the true point of celebration? I have not come to a conclusion as of yet.

The piñatas are just one aspect of your practice. You also work with illustration, video art, performance and life-size sculptural work. Does the medium dictate the idea or vice versa?

The idea dictates the medium for sure. For this new body of work, I allow thoughts and memory to rise back to the surface, and I do a lot of writing and recording. It’s a generative stage at first. Then I move into a rational state of awareness, and I make formal decisions between memories and medium. Are there materials that would enhance these memories? Are there methods that would align my work with the larger Mexican American-Chicano culture? What techniques would elicit a new understanding about the past and the present?

Tell us a little more about this concept of “art as experience.” How did you allow the “tactility of daily life” to become material for the work? Does this modus operandi relate particularly to your exploration of the natural environment? I’m thinking of works like “Natural History” (2015); “Ego Death” (2017) and “Totems” (2020).

That approach relates specifically to the work I created after settling in the Tahoe National Forest. I wasn’t expecting this, but when you move to the forest, your instincts kick in, and your focus becomes centered around survival. You survey your land, you look for animal tracks, you avoid no trespassing signs on neighboring properties, so you don’t get shot. You pay close attention to the weather, predators and wildfires, and try to stay safe.

Pacheco’s 2017 work “Ego Death” explores the natural environment

in the Tahoe National Forest, where the artist lives.

I enrolled in the MFA program at UC Davis in 2015, two years after buying my cabin. I submitted a portfolio of collages I had done in the past, and figured I’d carry on with that type of work while in the program. They quickly became pointless though, those collages. Superfluous. They just weren’t getting to the heart of the matter or teaching me anything about survival. I began transitioning my work soon after and started using art as a tool to categorize the lived experience. I documented my new surroundings like an archaeologist. I chopped down trees and recorded them falling. I created wayfinding markers that were embedded with narratives instead of directions. I embraced being lost in all of it. Strangely enough, this bewilderment became a compass over time.

Do you see a through line from works like “Natural History” to your piñatas?

Yes, absolutely. “Natural History” was the first project that focused on life in the forest, and it was my first attempt at forming an understanding of place. The installation was comprised of forest remnants within a half-mile radius of my cabin, and the act of cataloging the forest floor on white walls gave me new entry points into the work. The installation was a bird’s eye view of sorts, and it simplified a complex and interconnected ecosystem into bite-sized chunks. The piñatas are no different in that respect, despite being focused on identity and culture. Like “Natural History,” the piñatas are a first attempt at piecing together a bigger picture. They’re a broad stroke where I’ve combined a range of stories and memories together in hopes that they will reveal something previously unknown.

The artist’s 2015 project “Natural History” was made up of

natural materials found near his cabin, and “simplified a complex

and interconnected ecosystem into bite-sized chunks.”

In a 2017 interview with Placeholder magazine’s Aida Lizalde you talk about using your studio practice to process your move out into the Sierra Nevadas. What prompted that move and how did the studio, both literally and figuratively, provide tools for you to process it?

My wife and I bought our cabin after spending more than a decade hustling in the American rat race. We had been living in big cities up until then, and our lives were becoming centered around high-pressure jobs, long hours, high rent and takeout dinners. Rinse and repeat. I personally was losing touch with who I was and realized that we needed to make a change.

The big idea was, if we can buy a house outright, or close to outright, it might free up some time. If we didn’t have to scramble to pay a huge mortgage, perhaps we could quit our jobs? And then our focus, and our time, could be redirected elsewhere — towards more rewarding pursuits — like making art, having a garden, connecting with the universe and so on. It was a shift in lifestyle that we were after.

The studio became a representation of that for me — something that has embodied our new value system. An investment in ourselves. Luckily enough, the cabin we purchased came equipped with a 500-square-foot studio, and it has given me the time and space to think for once.

Thinking about the concept of movement, do you find that your practice blurs the disciplines of art and design? Or do you work consciously to separate Vincent Pacheco, the artist, and Vincent Pacheco, the designer?

I used to draw a hard line between my design and art practices. I started out my career working in Corporate America for Fortune 500 companies, helping the rich and the powerful become richer and more powerful. The experience was spiritually draining to say the least, and I didn’t want that type of work to cross over into my art practice — ever.

“Totems,” Pacheco’s 2020 work, featured a mix of manmade and

organic materials.

About 10 years ago I made the choice to shift my design practice away from corporations, and I now only do graphic design for clients I feel aligned with (nonprofits, educational institutions, fellow artists, etc). I feel good at the end of the day, and as a result, it’s become easier to accept graphic design as a part of my life.

Recently, I’ve begun implementing graphic design thinking into my artwork — incorporating language and taking cues from the marketing slogans I used to write for companies. Only instead of trying to convince someone to buy a product, I’m asking them to reconsider the nature of reality. I’ve also been incorporating iconography and symbolism heavily. The methods between art and design are starting to blur, and I’m excited to see where it goes from here.

Speaking of the future, what lies ahead for you?

Well, I’m excited to report that I got a new studio at Verge Center for the Arts in Sacramento and will be getting that up and running soon. I’d like to turn that into an installation space where I can experiment with creating art environments, and continue the line of work related to identity, family and my culture. Who knows where that will lead. But if I’m honest and do genuine work, maybe it will create new exhibition opportunities? Art sales? Spiritual oneness? All the above?

Edited for length and clarity.

–

–

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Art Exposed: Diana Ormanzhi

A Sacramento artist reinterprets surrealism through a feminist lens

At Twisted Track Gallery in Sacramento, which recently emerged as

a keystone of the thriving R Street art scene, one wall is

devoted to a triptych of the feminine divine.

Art Exposed: Alina Tyulyu

A lifestyle photographer becomes a war documentarian when she returns to Ukraine as a volunteer

The Sacramento-based photographer is traveling around her

native country of Ukraine to aid refugees during the

Russia-Ukraine war, documenting their experiences along the

way.

Art Exposed: Nancy Sayavong

The Roseville-based sculptor uses woodworking techniques for both art and remodeling

As a woodworker and metal fabricator, Nancy Sayavong uses her

training both for art and remodeling jobs. Her work is

interested in the contrast between the romantic ideal of the

home and its lived reality.

Art Exposed: Tasha Reneé

The local potter on the hazards of ceramics and making peace with impermanence

Tasha Reneé sells ceramics independently and through plant shops

and home decor businesses and is currently pivoting to teach

others through private lessons, workshops and classes.

Art Exposed: Jonathan Joiner

How a filmmaker and creative director mines the past for inspiration to create fantastical objects, stop-motion video and playful GIFs

Jonathan Joiner finds inspiration in retro-futuristic gadgets,

movies and “practical things.”

Art Exposed: Sarah Marie Hawkins

Multimedia artist Sarah Marie Hawkins uses a variety of methods

to tell not just her story, but the stories of many women.

Art Exposed: Donco Tolomanoski

Collage artist helps upcycle monthly art events into new vision

As lead organizer of WAL’s First Friday events, the collage

artist is focusing less on the “party” aspect and more

on the artists and their work.