Faucets on. Streets clear. Trash gone. Most city dwellers take for granted the infrastructure of daily life. And, except for monthly reminders supplied by bills, utility providers generally remain far from consumers’ minds.

That changed when a recent audit of Sacramento’s Department of Utilities uncovered operational inefficiencies and poor budgeting practices, bringing that provider to sharp consumer attention.

“The situation with the utilities is that they haven’t been adequately managed or adequately funded for quite some time,” says Sacramento City Manager John Shirey.

The same September week Shirey took office, former head of utilities Marty Hanneman left his post and was replaced by Dave Brent, a 20-year veteran of the DOU and most recently its legislative and government affairs coordinator, as interim director. Brent faces a list of city auditor recommendations while overseeing utility rate increases meant to help finance a $470 million infrastructure upgrade.

“As we currently stand, we’re investing enough money to replace our sewer system once every 650 years and our water system once every 400 years,” Brent says. “Those numbers far exceed the recommended design life of our infrastructure.”

Cities throughout the country struggle with investing in infrastructure replacement, he says, but relative to other California water agencies’ replacement cycles — ideally every 100 years — Sacramento ranks near the bottom. “It’s just not acceptable to have that kind of replacement cycle for backbone infrastructure that everybody relies on every day,” Shirey says.

As old, sometimes leaky, water pipes threaten to damage homes or business and outdated sewage systems prove inadequate, Sacramento utility rates rise. The city’s utility audit shows the monthly flat rate for unmetered residential water use, comprising 73 percent of the DOU’s water accounts, rose 104 percent from fiscal year 2002 to 2011. The biggest jump, a 13 percent increase to $34.35, occurred from 2010 to 2011, when the DOU had to play catch-up on payments lost from foreclosures and unpaid bills.

“We got saddled with millions of dollars in bad debt that we had to make up,” Brent says. Ratepayers also saw a 6 percent increase in sewer charges to pay for $150 million in regulatory improvement to the combined sewer system, plus increases for labor fees and water meters. Rates did not increase for fiscal year 2012, and Brent says costs remain reasonable relative to the services provided.

“Our water rates are about a dollar a day for pretty much unlimited use of water,” Brent says. “Our sewer rates are about 50 cents a day.”

Affecting rates are infrastructure maintenance costs to ensure compliance with federal and state municipal utility standards such as the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act.

“Our public water supply is incredibly safe. Our sewage treatment is incredibly advanced and protects us against disease,” Brent says. “All this is very important infrastructure. It’s time to start replacing some of it. It’s been doing its job 24/7 for 100 years, and things just don’t last that long reliably.

“Man, if our water had the same sort of unreliability (as cell phones), people would be going ballistic. … And my cell phone has a much higher bill.”

Sacramento’s ongoing recession, however, demands city officials show even greater attentiveness to inefficiencies and costs, and examining the utilities department was a top priority. In early 2010, city Auditor Jorge Oseguera studied DOU operations and issued a report disclosing seven findings predicted to save the utilities department — and ratepayers — an estimated $8.65 million in the current fiscal year and nearly $34.5 million in the next three years.

Brent says he’s examining each recommendation carefully with DOU officials and an internal audit response team. He cautions that not all of the recommendations will reap the projected benefits, pointing specifically to replacement plans for old water mains.

“In the older parts of the city, our forefathers, in their wisdom, put the public water mains along property lines in backyards. These are all older pipes that need to be replaced at some point,” Brent says.

In an effort to not intrude on a homeowner’s living space, utility workers have been re-plumbing the water mains that run through a property with new pipes that flow outward to the street, and installing the water meters there. The auditor’s recommendation, however, was to not replace the old water mains but to simply install the new meters in private backyards. This approach would generate an estimated savings of $31.4 million, which the auditor said could be directed toward capital improvement. The problem, says Brent, is that homeowners don’t want utility workers stomping through their backyards and tearing up the landscape to install a meter, and then perennially showing up to check it.

“As we currently stand, we’re investing enough money to replace our sewer system once every 650 years and our water system once every 400 years.”

Dave Brent, interim director, city of Sacramento Department of Utilities

“When the time comes to replace those pipes, we are not going to go digging up people’s backyards — a big trench through swimming pools and detached garages and rosebuds. We’re going to move the pipes out into the street,” says Brent.

Plus, he says, the possibility of old pipes failing is substantial; it has happened before and creates a costly mess.

“My assumption and my professional judgment,” Brent says, “is that ultimately (the auditor’s) recommendation would cost the city and the ratepayers more down the road because we would eventually have to replace those old pipes.”

He says the DOU is investigating a more cost-effective way to continue its current practice of saving ratepayers as well as rose gardens. He’ll present the findings to the City Council this month. “It is incumbent upon us to show why we would do something different than the audit suggests,” he says.

Brent also challenges the auditor’s recommendation that the solid waste department downsize its process for cleaning up green refuse left on the street. The suggestion was to replace the two-truck system with a single truck with one operator, a change the auditor says would save more than $4.1 million over three years.

“It sounds easy, it sounds good, but our solid waste guys say it’s not a panacea,” he says. Flying solo on the job decreases efficiency. Meanwhile, more Sacramentans opt to can their green refuse, so the DOU’s investment for loose-in-the-street collection already is sliding.

The solid waste department also is researching new software that could more efficiently route trash trucks and save a possible $720,000 leading up to fiscal year 2015. Cutting some of the round-the-clock staffing at water treatment plants also could save more than $1.7 million, the audit shows, so Brent and his team are examining whether reductions would threaten plant security. The DOU already eliminated 50 positions and left another 50 vacant after budget cuts.

“They are really minimally staffed as they are,” he says. “If something goes wrong, we need to be there.”

While addressing the audit recommendations, Brent and his team have moved on other initiatives.

The department established an operations-focused energy plan to regulate usage and is developing a comprehensive outreach strategy to educate Sacramento residents about proper recycling in hopes of maximizing the city’s return on recyclables. The auditor’s report shows both efforts would save a combined $2.5 million over three years.

The seventh finding resonates with Brent most. It reads: “Investment in capital assets is likely insufficient, the DOU’s capital plan is not well defined, and there are too few specific projects identified.”

Brent says the city agrees “100 percent.” Poor past planning has equated to increased efforts now to realign resources and repair the future of Sacramento’s utility services, namely water and sewer.

“We’re looking at and proposing a five-year capital program, in water a total of about $350 million and about $64 million over five years in our sewer,” Brent says. To ratepayers, the program ensures continued safety, but also continued rate increases to the tune of about $5.78 per month for the next three years, 10 percent each year for water and 14 percent, 15 percent and 16 percent annually for sewer. The program’s 30-year goals require investment of about $1.9 billion.

Though ratepayers must provide the bulk of the capital, Brent says the DOU stridently seeks additional funds to reduce the burden. “We’re pursuing grants, we’re looking at low-interest loans and everything else we can do to minimize rate increases. We’re going to do all we can to be good stewards of their money and to keep the rates as low as possible,” Brent says.

Two years ago, the DOU received $22.5 million as part of the federal stimulus package for Assembly Bill 2572’s water meter installation efforts, and recently the department banked a $6.2 million grant to improve the combined sewer system.

“There’s nothing more important to this city than the condition of the water and sewer pipes underneath the streets,” says Sacramento City Councilman Rob Fong, whose District 4 jurisdiction covers downtown and other high-priority areas. Fong is one of the council members to whom Brent will present the capital goals and ultimately request approval.

Although Fong says no one can argue with the importance of replacing aging infrastructure, the City Council’s highest task is asking ratepayers to agree. “I think people will have some heartburn over casting that kind of vote,” he says. “It’s politically difficult to ever raise anyone’s rates.”

After December’s resident notifications about the rate increases and a hearing with the Rate Advisory Commission on Jan. 25, the Council is expected to announce its final decision in February. If approved, the new rate structure would take effect in July.

Putting price in perspective, Dr. Sanjay Varshney, dean of Sacramento State University’s College of Business Administration, says economic reports indicate that in 2010 West Coast households spent less than 1 percent of their income on public utilities.

“How critical is water to you?” he asks. “If the water was not hygienic to drink and you felt sick, what’s the cost of that? If they did not upgrade the sewer pipes and there was sewer spillage someplace or sewage backed up someplace, what’s the cost of that?”

If City Council approves the plan, Varshney says ratepayers won’t be the only beneficiaries. Approximately $470 million in capital investment over the next five years could generate a total gross impact of roughly 6,450 jobs, $322 million in labor income and a total economic output of $858 million. Thirty years down the road, the DOU’s $1.9 billion investment could create 26,600 jobs, $1.3 billion in labor income and a total economic output of $3.5 billion, he says.

Though a jolt to the economy may sweeten the deal for ratepayers, what’s more compelling is the peace of mind. But that comes with a price, and it’s time to pay up, says Fong. “Every year that we don’t address it puts us in greater danger of catastrophic failure.”

Folsom

Transformations in Folsom extend beyond the recent $11 million Historic Sutter Street revitalization. Four key city positions also changed faces, including the fire chief, police chief and mayor. In October 2010, former Assistant City Manager Evert Palmer stepped into the lead management role.

“The council electing me rather than going to the outside is at least in part a message that there isn’t anything significantly broken,” Palmer says.

Palmer is focused on continuing agenda items, namely the multimillion-dollar, 6-square-mile annexation of the sphere of influence south of Highway 50. Former Mayor Andy Morin says the annexation expands city limits by 25 percent, does not cost the existing citizens of Folsom any money and should be secured by early 2012.

Currently operating with a $65 million budget and $4.1 million in reserves, Folsom shows a “noticeable uptick in the existing home sales in the city” as well as increased sales taxes, Palmer says. Property taxes, however — Folsom’s major revenue source — have suffered “significant declines,” he adds.

Evidence of an economic turnaround appears in the recent hiring at Intel Corp. and new business additions, including Whole Foods Market and country music star Toby Keith’s restaurant at the Palladio at Broadstone.

Elk Grove

Nearly 12 years after it’s incorporation, Elk Grove has doubled in population to more than 150,000 citizens and continues citywide development with a healthy but cautious fiscal outlook. “We’re relatively in good shape compared to where others might be in the region,” says Laura Gill, Elk Grove’s city manager since June 2008.

The city was able to boost its operational budget by 8 percent from last year to $149 million and now has a reserve fund of $13.6 million. The savings were made possible by raising the sales tax and some administrative restructuring that included employee furloughs, Gill says, adding that the belt tightening should not affect citizens. “Through the past three years, we haven’t cut police officers, we’ve added police officers,” she says.

With guidance from the city’s first economic development director, Randy Starbuck, Elk Grove plans a five-year, $250 million capital improvement plan that includes building a civic center to increase community traffic and job creation.

“Right now, we have the worst jobs-to-housing imbalance in the region … for us it really is about job attraction,” Gill says.

Last August, Region Builders, a coalition founded by the Sacramento Regional Builders Exchange, named Elk Grove the Best Local Government, and this year, citizens of Elk Grove will hold their first public vote for mayor.

Roseville

After dedicated frugality and a 10 percent, across-the-board staff reduction — resulting, for example, in a volunteer fire service — Roseville city officials say they are back in business.

“We finished the fiscal year 2011-2012 in the black, which I think is a very significant thing these days,” says City Manager Ray Kerridge.

With operating expenses at $111.7 million and reserves at $23.6 million, Roseville city officials are planning significant community initiatives, largely the new, $37 million town square to be unveiled in fall 2012, says Assistant City Manager John Sprague. “It will be like our living room, so to speak,” he says.

Rob Jensen, assistant city manager of operations, says a Roseville task force has formed to attract universities to the area. Development efforts will press on under advisement from the Redevelopment Advisory Committee and Roseville Community Development Corporation. Meanwhile, Roseville citizens recently petitioned to cap city management salaries. City Manager Kerridge declined commenting on his potential fixed salary, calling it, “An issue for the voters.”

Sacramento

Having presumably stopped a revolving door of city managers in Sacramento, John Shirey entered the seat on Sept. 1 facing a $26 million deficit and ongoing financial quagmire.

“We, as a city, are not out of anything,” says Leyne Milstein, Sacramento’s director of finance. “We have taken a lot of very difficult reductions, and it will not get any easier.”

With a $360 million general budget and 75 percent of city costs paid to labor, Milstein says reductions will continue to hit Sacramento’s public programs and services. “We have to reduce our costs of doing business,” she says. Reports show some City Hall salaries at record highs.

Mayor Kevin Johnson not only voted against Shirey’s $300,000-plus salary package (a more than 10 percent increase from the previous manager’s pay), but against the entire position as well.

“The relationship with the mayor is fine,” Shirey says. “We don’t have many differences and are working in concert on the arena project, which, of course, is a very high-priority project for him.”

Sacramento City Councilwoman Sandy Sheedy, however, says Sacramento is not ready for the arena and says a poll she conducted in the fall shows 72 percent of citizens want a citywide vote regarding the project.

“Until there is a financing package out there that does not include every asset the city owns,” she says, “it’s not ready.”

FairField

After four years of falling property taxes and a 40 percent cut to the city’s general budget, city officials say recent quarters finally show positive growth.

“We’re really attributing that to the rebound of our auto mall,” says Deputy City Manager David White. City officials estimate revenues at $50 million and say they achieved a balanced budget through reliance on the city’s 5 percent budget reserve.

Through the recession, Fairfield city manager Sean Quinn says he “continued an aggressive economic development program despite budget reductions.” The city is planning a new Capitol Corridor train station project slated to include 7,000 adjacent housing units and room for retail.

As executive director of the Fairfield Redevelopment Agency, Quinn vocally opposes Assembly Bills 26 and 27, which would eliminate redevelopment agencies. “If the (California) Supreme Court rules in favor of AB 26 and AB 27, we have made the decision that we will pay the funds as required under AB 27 to keep redevelopment,” Quinn says.

Under the legislation, which became law in 2010, cities could only keep redevelopment agencies if they met certain conditions that include funding schools and other agencies at a greater share.

If the court ultimately sides with Gov. Jerry Brown and the Democratic-controlled Legislature, Fairfield would owe $11 million this year and $2.6 million in future years, significantly diminishing funds for job creation and private investment, Quinn says.

Stockton

Declining revenues, property taxes and state funds prolong economic suffering in Stockton.

“We continue to be in a fiscal emergency situation,” says City Manager Bob Deis, who declared two budgetary emergencies this fiscal year but says $37 million in largely unpopular cuts managed to balance the budget.

“This council has been willing to make very, very difficult decisions,” Deis says, including negotiating with labor groups for reductions to compensation and benefits and increased contributions to retirement and medical insurance.

Now, teetering on a $160 million general fund, Deis says his biggest challenge is staying out of the red while maintaining levels of service in areas like economic development and public safety.

He predicts an onslaught of new jobs in the coming years on the heels of incoming Stockton infrastructure, including the Sperry Road extension (a 1,700-bed medical facility at the Department of Corrections) and the upcoming Delta Water Supply Project Deis announced his retirement last fall, but following pleas by council members to stay, those plans were put on hold. “I plan on sticking around for the foreseeable future,” he says.

He is also hiring a new team of directors in finance, human resources, economic development, municipal utilities and a new police chief — the fifth in about as many years.

Recommended For You

Keeping the Lights On

Behind the scenes with the Sacramento Municipal Utility District

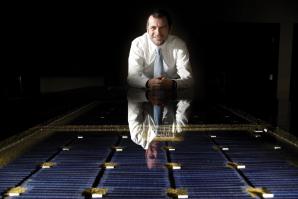

A backstage look at how the crew at SMUD keeps Sacramento lit up.

Golden State

A Folsom company thrives on SoCal sun

It didn’t take German immigrant Martin Hermann long to see California as the land of sunshine. And within that bounteous golden glow, he imagined opportunity.