In 2001, new strains of stripe rust — an aggressive wheat fungal disease typically associated with cooler, damper climates — began to emerge in California. The new strains were more virulent and better adapted to warmer climates throughout the world.

By 2003, the strains had caused an epidemic in the U.S., wiping out 25 percent of California’s wheat crop, says Jorge Dubcovsky, plant geneticist and professor of plant sciences who leads the small grains breeding program at UC Davis.

That’s a significant threat, considering wheat is the world’s second-highest produced grain behind corn, according to Statista, a market data provider. “We produce more than 750 million tons of wheat every year in the world, and this is 20 percent of the calories and 23 percent of the protein consumed by the global population,” says Dubcovsky. As the population grows, increasing the demand for wheat while arable land decreases, the ability to produce more wheat by reducing loss to disease and improving nutritional quality becomes a matter of global food security.

A 20-year study led by Dubcovsky and his colleague Tzion Fahima, head of the Laboratory of Plant Genomics and Disease Resistance at the Institute of Evolution at University of Haifa in Israel, was recently recognized by the U.S.-Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund’s 40-year research impact assessment released in the fall of 2020.

In that assessment, BARD estimates the funds it has invested into Dubcovsky and Fahima’s work will contribute a median net contribution of $118 million in savings to the world economy as wheat varieties with improved nutrition and stripe rust resistance secure an increased premium and reduce the need for fungicides, says Yoram Kapulnik, executive director of BARD.

Gene Discovery

At the time of the crop devastation in the early 2000s, Dubcovsky was working on identifying a gene in wild emmer wheat found in the Fertile Crescent — the region in the Middle East known as the birthplace of agriculture — responsible for improved protein and micronutrients. His joint research with Fahima was funded by the first of five three-year consecutive grants from BARD to identify the gene and transfer it into commercialized wheat varieties.

During the course of Dubcovsky and Fahima’s research funded in part by BARD — which contributed a total of $1.47 million between 2001 and 2016 — the pair shifted their research, identifying and cloning two new stripe rust resistant genes in wild emmer wheat and mapping several others. The discoveries were not the first known genes resistant to the rust, but they are significant because as new strains evolve, some resistant genes become ineffective.

As it turned out, one of the newly discovered genes was closely linked to the gene that controls the levels of protein and micronutrients such as zinc and iron in wheat, which meant they could produce new cultivars of wheat (human-made varieties) that could be stripe rust resistant and have an improved nutritional profile, Dubcovsky says.

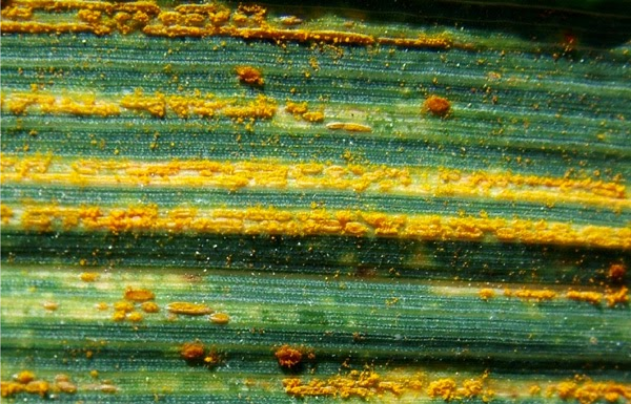

Stripe rust, an aggressive wheat fungal disease, wiped out 25

percent of California’s wheat crop in 2003. (Photo courtesy of UC

Davis wheat breeding program)

The team’s discoveries were widely shared, in keeping with a fundamental practice of public universities to disseminate scientific research for the greater good as well as drive innovation within the private sector that capitalizes on the findings and fuels the economy.

“Sixty-five percent of the varieties in the U.S. are produced by universities, (the) United States Department of Agriculture and the public sector. … That has made the international community of wheat a very collaborative group of people, so we try to share as much as possible,” says Dubcovsky.

The new genes have been transferred to wheat varieties that are grown in the U.S., Canada and India, and that distribution is expected to grow.

Rebuilding California’s Wheat Market

In California, approximately 80 percent of hard red (high protein) and hard white (moderate protein) wheat cultivars are stripe rust resistant, says Claudia Carter, executive director of the California Wheat Commission, which provided $250,000 toward the BARD projects.

California Wheat Commission Executive Director Claudia Carter

stands in a field of Summit 515 wheat, one of the most widely

planted hard red wheat cultivars in California, with stripe rust

resistant genes. (Photo courtesy of California Wheat Commission)

To reverse that trend, the CWC began funding the UC Davis wheat breeding program to benefit from the university’s research and revitalize the market. “My mandate in a land grant university is to serve the agriculture of my state, so the wheat growers are an important constituent of my program and I do all I can to help,” says Dubcovsky.

He and his team developed and released 19 wheat cultivars through UC Davis’ wheat breeding program over the past 23 years, all specifically adapted to grow in California, improving the state’s quality of wheat. Some of those cultivars have been developed in collaboration with companies such as Research Seeds (later purchased by Syngenta), which produced Blanca Grande 515, the most widely planted hard white wheat, and Summit 515, one of two most widely planted hard red cultivars in California.

But rebuilding the state’s wheat market has been tough. Large California mills have become accustomed to purchasing large amounts of the grain from producers outside the state for less, and California farmers don’t produce enough to warrant a one-year contract, says Carter. Except for its Desert Durum wheat — a joint trademark held by California and Arizona that is exported to Italy — California’s wheat market remains within the domestic boundaries of the state. Even then, only 100,000 of the 385,000 acres planted in 2020 were harvested for human consumption, Carter says. The rest was processed as animal feed.

Carter says the CWC’s efforts to increase the market are targeted toward smaller farmers who are focused on sustainable and regenerative agriculture and small mills “that are booming right now,” such as Capay Mills based in Yolo County and Grist & Toll in Pasadena, that want to support local farmers and will pay a premium for their crops.

While wheat isn’t as profitable as other crops such as tomatoes, it’s an effective rotational crop, used to break the cycle of pests and disease. And many California wheat producers minimize tillage of the crop, retaining soil structure and allowing the crop’s residue to decompose and build soil health.

And the stripe rust resistant cultivars Dubcovsky and his team have developed allow California growers focused on regenerative practices to grow the crop without the use of fungicides or the risk of losing yield to the disease, at least for now.

“Food doesn’t grow in supermarkets. And you need to be out there fighting with pathogens and other things to keep your food coming,” says Dubcovsky. “Well, (with) this year of pandemic, you probably understand why it’s better to have knowledge about these pathogens.”

–

Tell us what you want to see in Comstock’s: Take our reader feedback survey and be entered to win a $100 gift card.

Recommended For You

Shouldering the Burden

Progressive-minded farmers in the Capital Region undertake steps to battle and adapt to climate change

A growing movement of farmers is focused on agricultural practices that can mitigate or adapt to an uncertain future brought by climate change.

Part of this month’s Innovation issue

Change in the Grapevine

Capital Region vineyards and wineries are cultivating an environmentally friendly way of life

In the Capital Region, there’s an emerging market among boutique vineyards and wineries focused on low-intervention farming and production methods.

Protecting Open Land

California Rangeland Trust project places fiscal value on the environmental benefits of ranches

Ranchers and those in the conservation industry know there’s an inherent value to working lands, such as cattle ranches. But how do they monetize that value?

Seeds of the Future

What does it mean to be the ‘Farm-to-Fork Capital’ during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Here’s how four businesses are engaging in the Capital Region’s farm-to-fork economy and have adapted to the pandemic so far.