Stan Van Vleck, owner of the 13,000-acre Van Vleck Ranch in Rancho Murieta, is incrementally placing 30 percent of his ranch under conservation easements, with nearly 1,800 acres conserved to date.

“We’re going to be one of the largest private dedications of land in our region,” says Van Vleck, whose cattle ranch accounts for 5 percent of all agricultural land in Sacramento County.

Positioned between Deer Creek Hills Preserve and Gill Ranch — both working ranches with land under conservation easements — Van Vleck’s conserved land creates a vast corridor of preserved habitat among the three properties.

Ranchers and those in the conservation industry know there’s an inherent value to working lands, such as cattle ranches that are a signature of California’s landscape with rolling hills, grazing herds and oak woodlands. But how does one monetize that inherent value?

That’s the question California Rangeland Trust, a Sacramento-based nonprofit land trust, asked UC Berkeley scientists to answer. The yearlong study, which began in 2018 and was released in August 2020, was funded by donations from the Resources Legacy Fund, a nonprofit dedicated to conserving natural resources, and an anonymous donor. The study calculated the fiscal value of environmental benefits (called ecosystem services) from 56 of 82 ranches throughout the state under conservation easements with California Rangeland Trust, totaling 306,718 acres.

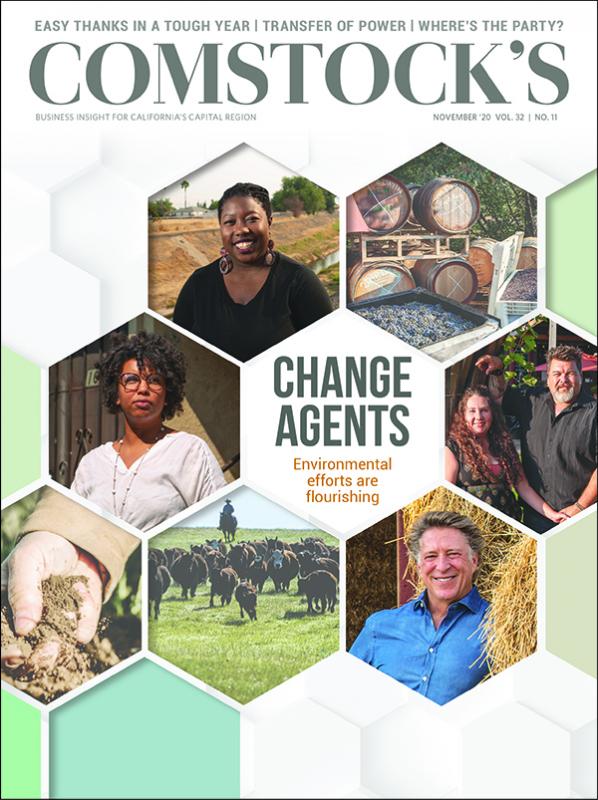

Most of the Yolo Land & Cattle Co.’s 7,500 acres is under a

conservation easement with California Rangeland Trust. (Photo

courtesy of California Rangeland Trust)

The value of the ecosystem services to all Californians provided by those working lands — such as clean air, carbon sequestration, groundwater recharge, clean water, recreation, wildlife habitat, biodiversity and climate regulation — were monetized at $346 million to $1.44 billion a year. Scientists used two methods found in the available scientific data valuing ecosystem services, accounting for the wide range in financial benefits, and found the method used to derive the value of $1.44 billion the most transferable to California rangeland.

“When (working lands) return $1.44 billion just for these 306,000 acres to constituencies in California, that’s an amazing return,” says Michael Delbar, CEO of California Rangeland Trust.

Between 1984 and 2014, more than 1.4 million acres of California’s agricultural lands were lost — nearly three-quarters of that was prime farmland with the best soil for agriculture — primarily due to urbanization, according to the California Department of Conservation. But in recent years, funding for conservation easements has declined. That’s created a competitive market for limited public funds.

“We’re going to be one of the largest private dedications of land in our region.”

Stan Van Vleck Owner, Van Vleck Ranch

“We actually have another 200,000 acres of willing landowners, 75 families, that have taken this step to apply to us for a conservation easement … while we try to locate the funding necessary to permanently protect those ranches,” Delbar says.

Voter-approved state bonds concentrated on agricultural land conservation used to be a primary source of funding easements when California Rangeland Trust opened its doors in 1998 but are no longer a focus of recent bonds, he says. “So now when we meet with a policymaker, we (can) say, ‘Hey, this is really important to support more conservation funding for ag land conservation, and this is how important it is,’” says Delbar.

Under conservation easements, ranchers sell or donate the development rights of their land (or a portion of it) to a land trust while retaining ownership of the land and managing it as a working ranch. The easement remains with the title of the property, restricting development and ensuring the land and its ecosystems are preserved in perpetuity.

At the Van Vleck Ranch in Rancho Murieta, the land and its rich biodiversity, with oak woodlands, vernal pools, wetlands and habitat for protected species such as Swainson’s Hawk, fairy shrimp and burrowing owl, is used for mitigating sensitive habitat or protected species affected during development elsewhere in the region, which can earn a higher easement compensation.

Van Vleck is using that compensation innovatively to diversify the 164-year-old family business. “Expecting someone in each generation to come back and say I want to be in the cattle business is highly speculative … (and it puts) undue pressure on your family,” he says.

Van Vleck launched an investment company with the mitigation easement funds, creating myriad business opportunities across sectors for future generations. His approach may serve as a model for others who are looking to preserve their land, ranch and family business.

But California Rangeland Trust isn’t looking to monopolize all of California’s working land and recognizes the balance that must be struck to provide homes for people, wildlife and livestock and the infrastructure society needs to thrive.

“We all need a place to live, and we’re not opposed to residential or commercial or industrial development … because we all need that,” Delbar says. “What we’re looking at is what’s a responsible way to do that.”

“We all need a place to live, and we’re not opposed to residential or commercial or industrial development … because we all need that. What we’re looking at is what’s a responsible way to do that.”

MICHAEL DELBAR CEO, California Rangeland Trust

California Rangeland Trust ranks and evaluates ranches under consideration for conservation easements according to factors such as location, development pressure and attributes that are attractive to available funding sources, Delbar says. For example, protecting a ranch with endangered species would be attractive to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, whereas protecting a ranch with timber resources would appeal to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

The majority of funding is secured through a competitive grant process for state and federal dollars on an easement-by-easement basis from agencies such as the Wildlife Conservation Board, Bureau of Reclamation and National Resources Conservation Service. While federal funding provided through the Farm Bill remains consistent, it’s a much smaller percentage of funding and must be matched by state funds, which means a decrease in state funds affects available federal dollars as well. In 2019, California Rangeland Trust received nearly $12.5 million in state funds and more than $3.1 million in federal funds.

But the team of UC Berkeley scientists wanted to do more than calculate the value of the environmental benefits to society from working lands. They wanted to evaluate whether those investments in conservation easements were the right ones. In other words, they wanted to calculate the return on investment.

Rominger Brothers Farms near Winters in Yolo County is one of 82

ranches in California under conservation easements with

California Rangeland Trust. (Photo courtesy of California

Rangeland Trust)

“Whether (a ranch) was really the right investment depends on whether the flow of (environmental benefits) would have (been lost) if we hadn’t spent the money,” says Lynn Huntsinger, professor of rangeland ecology and management at UC Berkeley and one of three scientists who led the study.

For example, if a ranch would never be developed — even without a conservation easement — because it lacks water or the land is too steep or is located too far from significant population, Huntsinger says, then a conservation easement would not show a good return on investment on that property.

Huntsinger and her colleagues evaluated three scenarios to determine whether a property would have been developed or not and calculated return on investment. They looked at the highest and best use determined by an appraiser, the county’s general plan that identifies if a property is in a region slated for development and if the property was planned to be fully developed, wiping out its environmental benefits.

The greater the development, the greater the loss of environmental benefits, the greater the return on investment for properties under conservation easements. Under the three scenarios, the county’s general plan allowing for maximum development under current zoning was most applicable to California, returning $3.47 per dollar invested for all California Rangeland Trust easements.

While the value of environmental benefits is in the billions, it could be a conservative figure. Huntsinger says some environmental benefits from working lands — such as fire suppression and the value of grazing — weren’t included in the study because there’s no available data on their monetized value.

California Rangeland Trust ranks and evaluates ranches under

consideration for conservation easements according to factors

such as location, development pressure and attributes that are

attractive to available funding sources. (Photo courtesy of

California Rangeland Trust)

With record-breaking fires scorching the West Coast this year, fire suppression is critical to California’s future. Huntsinger says much of California’s grasslands contain nonnative vegetation and are larger, denser, thicker and more flammable, and grazing offers a safe, viable option to reduce fuel loads.

While the study leverages scientific evidence to encourage policymakers to refocus on conserving agricultural lands, Delbar thinks it will also raise awareness among those who drive through open land and appreciate what they see.

“It’s telling the story of what all is there besides that open space,” says Delbar. “How all these services provided by these working lands are so valuable, but for a person (who’s) not in the livestock or ranching business, (he or she) may not realize that there’s more to it than just open fields.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Seeds of the Future

What does it mean to be the ‘Farm-to-Fork Capital’ during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Here’s how four businesses are engaging in the Capital Region’s farm-to-fork economy and have adapted to the pandemic so far.

Transfer of Power

Some owners who want to sell decide the best buyer is their staff

Research indicates that employee ownership can improve profit margins and company culture, but it may not be the right choice for every seller.

Fields of Gold

The Sacramento Valley’s climate is ripe for producing quality olive oil

Olive farmers in California are determined to become known as producers of high-quality olive oil, and much of that olive oil is being produced in the Mediterranean climate of the Sacramento Valley.

Laying the Groundwork

A widespread effort to achieve environmental justice in Sacramento is gaining momentum

Proponents say environmental justice efforts will only be successful if they are inclusive and equitable.

Comments

This is all great! We hope to do the same with our ranch someday!