Danielle Walters loved living in a tight-knit neighborhood in Sacramento’s Arden Park. But over the years, as she tended to her garden and raised chickens in her backyard, she felt a tug toward a more spacious existence.

In 2017, with her son away in college, Walters began to more seriously explore making her dream of rural living a reality. At first, she thought she’d buy some land and eventually build a home of her own. But that February, she stumbled upon a sprawling 48-acre property just south of Jackson in Amador County, an hour’s drive from her Sacramento home.

A simple two-bedroom fixer-upper sat atop a mile-long drive. On a clear day, she could see Mount Diablo in the distance. Walters, who works remotely for a biotech company, was in love. “As I walked down the ridge and up and down the property, I felt, ‘I’ve got to be here,’” she says.

In May of that year, Walters packed her bags and entered a new chapter of her life. Walters realized a dream shared by many but achieved by a relative few. Rural areas make up 97 percent of the land in the United States, but house only about 20 percent of the population. And despite polling showing one in four Americans would choose to live in a more rural area if they could, rural communities across the nation have struggled to maintain and grow their population bases and economies. In California, at least 13 of the state’s 36 rural counties saw their populations decline between 2017 and 2018, state Department of Finance estimates show.

Some of that loss comes from residents leaving as they age and need better social services and medical care, says Justin Caporusso, vice president of external affairs for Rural County Representatives of California. But it’s not just seniors fleeing the countryside. A lack of economic development, broadband access and job training are prompting students and young people to leave home for more urban areas across the state. Now, ongoing ramifications of Northern California’s intensifying wildfire season, including power shut-offs and skyrocketing home insurance rates, are presenting fresh challenges for residents and communities in the 10-county Capital Region.

Living Simpler

Rural living can take many forms: a ranch where cattle roam as far as the eye can see, a homestead on acres of fertile farmland, a remote cabin tucked deep in the woods.

The U.S. Census definition of “not urban” — in the most basic terms, areas with fewer than 1,000 people per square mile — leaves room for interpretation and debate. That metric, Census demographers acknowledge, “encompasses a wide variety of settlements, from densely settled small towns and ‘large-lot’ housing subdivisions on the fringes of urban areas, to more sparsely populated and remote areas.”

“For the average American, rural is an abstract concept of rolling hills and farmland rather than a concrete definition,” the Census’ Rural America portal explains. “Thus, it can be a difficult task trying to define the term ‘rural’ and an even harder task trying to explain it.”

Given the range, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that, for many, an understanding of rural living is less about population numbers and topography and more about a sense of being. Country singers croon about wide open spaces. Social media influencers, Food Network stars and glossy magazines deliver “rustic” recipes and lifestyle inspiration to the masses. For many, rural conjures visions of a more peaceful alternative to the frenetic and technology-tethered bustle of modern life in the city.

“You know what I like?” former Gov. Jerry Brown, who decamped to a 2,500-acre family property in Colusa County after leaving office in 2019, once told The New York Times. “You get up in the middle of the night, the stars are very bright, the moon shining on the barn. It makes for a good balance between the intensity of the political and the serenity of the land.”

Like Brown, Walters craved a return to a simpler life that allowed her to feel more connected to the land. Growing up, she spent summers visiting her grandfather’s ranch in Oregon. He grew his own food and raised a small herd of cattle. Christmas gifts, she says, were a side of beef. When her own son was young, they’d spend weekends camping in the woods. “I just kind of realized that was where I was most at peace,” she says. “(I) really enjoyed the outdoors and animals and all those other things.”

But, like many mulling a move from urban or suburban centers to the country, she also wanted access to amenities and modern life. Her closest neighbor is a quarter of a mile away. Instead of stopping by on a walk around the block, they roll up to her gate on a horse or ATV. But she’s also a nine-minute drive to a Raley’s grocery store. Walters calls the balance between privacy and convenience “the best of both worlds.”

“There (are) a lot of folks that are far more remote, and that’s a different thing. They’re making it to town once every two weeks for groceries,” she says. “I’m definitely more of a hybrid. I have a lot of space: I can hike on my property for a couple of miles and stay on my property, but I’m not so remote in access, whether it’s to groceries, the hospital, hardware stores, most importantly, Tractor Supply.”

Niesha Fritz has also found sanctuary in nature without giving up some of the trappings of modern life, including a career in Sacramento. Like Walters, Fritz had long felt an itch for rural living. In 2013, after splitting with her first husband, the Land Park resident stumbled across a rental farmhouse listing online. “I thought if I don’t do this now, it might be one of those things I always wonder about,” she recalls. She packed her bags and headed south to Wilton.

The transition wasn’t always easy. With no farming experience, the Los Angeles native had to learn everything from goat vaccination to installing irrigation. When she wasn’t working or chasing after her two young children, Fritz spent hours reading books, watching YouTube channels and chatting with friendly neighbors for advice.

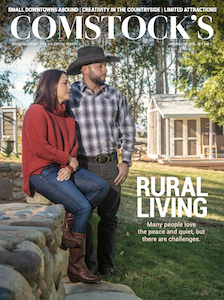

But there were pleasant surprises too. Her search for the perfect farm truck (an orange 1974 Chevy) led her to meet a man she would later marry. She and Ken, along with their three children, now live on a 5-acre property called Rocking K-N Ranch on the edge of Wilton. “It’s so quiet,” she says. “At night, we walk outside, and it’s silence, except when the goats start yelling to me.”

Simpler doesn’t necessarily mean slower. Both Fritz, who works as a legislative staffer, and her husband, who owns a construction and engineering company, commute from the ranch to the Sacramento area for work. That 40-minute (on a good day) commute is bookended with chores, including tending to their 16 animals, ferrying their children to 4-H meetings and planning projects like a second gravel driveway for the cattle they hope to someday raise.

“By the time we hit the bed, it’s like, ‘Oh, my God, I’m exhausted,’” she says. “That to me is what this kind of life encapsulates. The beauty of it is you can customize it and make it yours.”

Katie and Kris Biggi have eight show-quality Angora goats on

their 5-acre property in Newcastle, where they moved in May 2019.

Kris and Katie Biggi also envisioned a life in the country long before they were able to make the move. The couple was living in East Sacramento when they began house hunting in Newcastle. They found the perfect home, but Katie wasn’t quite ready to make such a drastic lifestyle change. “Coming from East Sac where she walked our then 5-month-old daily around the McKinley Park neighborhood, she wanted more of a neighborhood feel,” Kris says. “So we moved to Rocklin.” They ended up staying for four years.

In May 2019, the couple and their two young sons packed up and moved to Newcastle, where they now live on a 5-acre ranch with five separate pastures and a 1,200-square-foot barn. They have eight show-quality Angora goats, and the goal is to eventually have around 25, “focusing on top-quality genetics and bloodlines,” according to Kris.

“We ultimately decided that raising two boys with space to get dirty made so much sense,” Kris says. “The country lifestyle is something that we wanted our children to grow up in. Every day is an adventure out here with young boys and animals. We are so happy we made the move.”

Wildfire Anxiety

Lori Wilson was left with nothing after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Her rental home in New Orleans was destroyed. Her health was in decline. When friends from Northern California reached out with an offer to help, she jumped. “I literally had to pick myself up from having nothing,” she says.

The move to Auburn changed her life. She quit drinking, lost weight and found success in a new career producing hazard disclosure reports for real estate agents. In 2014, she purchased a two-bedroom chalet surrounded by trees in Pollock Pines. She found she could get more for her money in the rural community, and she loved access to nature, especially the Rubicon Trail. Sitting on her porch, she can hear coyotes in the distance. Deer run through the yard. The closest neighbor is barely visible through the trees.

“It’s the quality of life you choose,” Wilson says of rural living. “Yes, we have to drive a little farther, but you come home and you’re in your own little paradise.”

But recently, rural life has felt less serene. Soon after the Camp Fire ravaged Paradise in 2018, Wilson received word that her home insurance company was dropping her due to fire risk. After calling nearly a dozen agents, she found a new plan. But it would cost her: She now pays two-and-a-half times more than what she did before. “I never would have qualified for that payment had I applied for the loan today,” she says of her new monthly housing costs. “It’s unbelievable that people have to deal with that.”

Walters also faced sticker shock over the rising price of fire insurance; the cost of her plan tripled this year. Still, Walters was grateful her coverage wasn’t canceled like some of her neighbors. Her first summer in the house, a fire broke out nearby that was “too close for comfort.”

To mitigate that risk, Walters made an evacuation plan for her animals and added 5,000 gallons of above-ground water storage. She took in a small herd of Asian water buffalo, whose appetite for grass helps with fire prevention. “The stress around fire season was something I didn’t anticipate,” she says. “When that first rain happens, there’s a sense of relief.”

State officials responded to fire coverage concerns in December, temporarily banning companies from dropping policyholders over wildfire risks. The one-year moratorium was expected to cover at least 800,000 homes.

But other fire-related challenges have also emerged for rural residents. Pacific Gas & Electric shut off power in parts of Northern California three times in October and once in November, aimed at lowering the risk of fires, and the company said 177,000-970,000 customers were affected by each shut-off. Wilson was one of those residents. For 11 days in October, she hauled gallons of gas — about $50 a day — to her generator. She plans to invest in more solar panels and storage to prepare for future outages. As her costs increase, Wilson is wondering how long she’ll be able to afford to stay in the home she’s grown to love. The idea makes her tear up. “I finally got to a place in my life where I felt like I’m doing good, I’m going to be OK, I’ve overcome, and now I feel like I’m going back to square one,” she says.

A Shifting Population

Natural disaster fueled by a changing climate and skyrocketing insurance rates aren’t the only threats to rural life in the Capital Region. Rural communities are older (and whiter) than the urban cores where the vast majority of the state’s population lives. Fewer rural residents are in California’s labor force compared to their urban counterparts, and those who do work make less. The state is one of six where income inequality is higher in nonurban communities.

Closing the gap is a challenge. Spotty broadband access and a lack of job training are “creating a major roadblock to economic development,” Caporusso says. As a result, young workers flee to urban areas in search of education and jobs. That rural flight and an inability to attract new businesses translates into property and sales tax losses. Faced with declining revenues, communities are turning to new ways to pay for basic services, such as schools, hospitals and emergency response. And voters aren’t always willing to pay. In August 2019, residents of one fire district in El Dorado County rejected a $96 a year property tax increase that would have generated $2.6 million annually and paid for more firefighters.

There is no one-size-fits-all policy fix for California’s diverse rural communities, advocates say. The push for additional development, whether adding affordable housing stock or bringing new industries to replace agricultural losses, can have unintended consequences. “In rural communities, the planning goals are often: We want to stay rural, we want to keep agriculture,” says Catherine Brinkley, an assistant professor at the UC Davis College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences. “Yes, we want to keep growing, but we want a vibrant small town. Those goals are often at odds with development and housing.”

Fran DuChamp, an activist living in Pollock Pines, experienced the challenge of making ends meet in a rural community after moving to the region to help an aging relative 30 years ago. Several units shy of her teaching credential, she relied on substitute gigs at local schools to pay her bills. At one point, she went to a local gas station and begged for a second job at the deli counter.

DuChamp, now on Social Security disability, sees the need for more economic opportunity, but she’s also wary of development that will change the character of the community. “If people don’t fight back, someday it’s going to be like LA,” she says. “None of those open fields will be there.”

Even with questions about preservation and long-term economic sustainability of rural communities — not to mention the personal challenges of adjusting to a more agrarian lifestyle — many transplants say they have few if any regrets.

Walters, for example, says her move is panning out even better than she imagined. She began raising chickens and turkeys for meat. She acquired two dwarf goats, who she soon learned are better at being cute than mowing the lawn, and a rescued miniature horse named Chip. When she’s not busy puzzling out a new problem or project, she hikes her property and soaks in her view from her porch. Her “security dog,” Bubbles, is often at her side.

“This is my gym, definitely, it’s my hobby, it’s my office, it’s my weekend house, it’s my weekday house,” she says. “It’s everything wrapped into one.”

Comments

Enjoyed the article very much......Perhaps even more as Danielle Walters is my daughter....she does have the best of both worlds. The ability to split between her rural ranch life and yet still be active in her professional world. She was always good with pets but who would’ve thought she’d have a herd of water buffalo, miniature goats, mini horse, chickens, turkeys, Walter, the pig and Bubbles her dog? It has been a joy watching and hearing about her adventures on life in her foothills ranch.

So glad a love of the country life lured you to new adventures. Enjoy and be grateful.