Alyssa Roost knows how to open a restaurant. She knows what to expect. When she opened Vine+Grain (a wine and craft beer bar) and Attraversiamo (a farm-to-fork restaurant) in Brentwood, each time she received about 100 resumes. About half were qualified applicants, giving her plenty of choices for hiring a strong team.

Then she tried to expand during COVID-19. Technically her business is growing during the pandemic, but beneath the surface, it’s a more complicated story. In September 2021, Roost and her husband Anthony (both co-owners) opened a new location of Vine+Grain in the heart of Downtown Commons in Sacramento. Only 50 resumes rolled in and only a handful were qualified. Instead of hiring a team of 10, she could only hire six. So they slashed some of their hours from 11 a.m.-9 p.m. to 3 p.m.-9 p.m., and the wife-and-husband duo, who are also raising a 1-year-old, are now working 15-hour days. Instead of focusing on marketing in the office, Roost is waiting tables and her husband is back in the kitchen cutting a wheel of imported cheese.

“I have a lot of optimism,” Roost says about her forecast for 2022. “But we’re much more anxiety-driven than we have been in the past.” Roost could just as easily be commenting on the 2022 economic outlook for the Capital Region. Cautiously optimistic? Yes. Flooded with risks and caveats and nuance? Absolutely. “I gave up trying to predict things about 15 months ago,” says Mike Testa, president and CEO of Visit Sacramento. “But my sense is … we’ll continue to go in the right direction.”

“I have a lot of optimism. But we’re much more anxiety-driven than we have been in the past.”

Alyssa Roost, co-owner, Vine+Grain

Many of the region’s economic thinkers agree that the “right direction” is likely, but the headwinds of inflation, labor shortages, housing prices, never-ending remote work and inequity will continue to dog the region. The economy is like everyone’s favorite term in dating: “It’s complicated.”

First, the good news: People are traveling, dining out and seeing live music again. Even with the lingering delta variant, a gauntlet of events (like the 4-day Aftershock festival) brought foot traffic back to downtown — 42 events in October through December alone, according to Michael Ault, executive director of the Downtown Sacramento Partnership, “and we’re starting to see retailers benefit from that in a huge way.” Roost sees that spillover in the new Vine+Grain. “More people are coming our way,” she says, specifically citing concerts.

The same energy is seen in Placer County. “In Roseville, our large mall (Westfield Galleria at Roseville) is thriving and surpassed pre-pandemic sales,” says Scott Alvord, chair of the Placer County Economic Development Board and City of Roseville council member. “Our unemployment is back to pre-pandemic levels and our commercial vacancies, other than office vacancies, are pretty low.”

Both Ault and Testa expect the strength of events to continue into 2022, especially since events that were canceled due to COVID-19 have been rescheduled for the new year — 2021’s loss could be 2022’s gain, even if they fail to reach the pre-pandemic level of 586 in 2019. Specifically, Testa says a total of 71 events were canceled in 2021. Of those, 17 have already booked for 2022. “I’m confident that (we’ll) get all of them back, it’s just a matter of when.”

Another barometer of economic health: hotel occupancy. Sacramento hotels are now between 40 – 60 percent full, according to Testa — well above 16 percent from the depths of 2020 but still lagging the pre-pandemic heyday of 83 percent. Look deeper and you’ll see a red flag. Testa says pre-pandemic the hotels were always packed midweek and then lighter on the weekends. Now that has flipped. The weekends have recovered but the midweek is soft. “What that tells me is that a lot of leisure travel is happening,” Testa says, “but what’s still behind is the business travel.”

And this is where the concerns begin.

The risks

If business travel is behind, so is the number of people who are actually at the office and doing business. No one thought that would be the case. Earlier in 2021, plenty of companies “talked to their staffs and did polls and said, ‘In June 2021, we’re going to be back!’” says Amanda Blackwood, president and CEO of the Sacramento Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce. Then came reality. Now Blackwood is skeptical that much of downtown will return to the office, particularly in the government sector.

Vine+Grain restaurant in Sacramento’s Downtown Commons is just

one of many businesses affected by the ongoing pandemic.

“The behavior of the state would indicate to me that some (employees) will come back, but it’s not going to be with fully-staffed buildings,” Blackwood says. She suspects government departments like human relations, finance, administration, compliance and risk management — jobs that can be done remotely — will continue in that direction. Specifically, she notes the state is investing in training for how to work remotely, and that this is a clear signal of its intention, “short of a press release saying we’re never coming back.”

Barry Broome, president and CEO of the Greater Sacramento Economic Council, agrees that a full return to the office is unlikely. “I don’t think you’ll see more than a third to 50 percent of that recovery,” Broome says, and adds a hybrid workplace is “probably going to be a permanent part of the future. That’s going to sting and the downtown is going to be affected.”

Revenue for small businesses is only one slice of the economy. Consider the challenge of housing. Even if COVID-19 trends improve in 2022, housing in the region is likely to become even less affordable for the average family, says Sanjay Varshney, principal and founder of Goldenstone Wealth Management and founder and chief economist of the Sacramento Business Review (and Comstock’s Editorial Advisory Board member). “Eighty percent of the households in Sacramento cannot afford the median home,” Varshney says, adding the gap is between $30,000 and $45,000, depending on the neighborhood.

That housing gap is at current prices with current interest rates. In 2022? “Inflation is showing its ugly head,” says Varshney, who predicts if the Federal Reserve begins tapering its stimulus, that will of course raise the 30-year borrowing rate, which will “change the game

plan for Sacramento.” Here’s how: Varshney says for every 100-basis-point change in the mortgage rate, the buying power changes by 12 percent. In 2020, mortgage rates plunged 100-150 basis points from their prior baseline (from 4 percent to 2.5 percent), and if they snap back to historical levels, buyers could “see another 25 percent loss of purchasing power.” The current problem could become a future crisis. Broome notes supply chain problems could further accelerate the cost of construction, making the problem — or crisis — even worse.

Inflation looms over everything. When Visit Sacramento produced the Farm-to Fork-Festival this past September, the costs were up a whopping 30 percent. The table and chair vendors, the linen providers, the cost of security guards — all of these costs were higher, and this was before the national news announced October prices were 6.2 percent higher than the previous year, the largest increase in three decades. At Vine+Grain, Roost says all of her costs have “increased significantly, and this creates a chain reaction on our menu.” She does her best to avoid hiking prices, but it’s tough when the cost of paper, for example, is 50 percent higher than February 2020. It’s easy to see a scenario in 2022 where people can’t stomach the higher prices, eat out less, and the lower demand creates a vicious cycle that stalls the economic growth. Testa notes when flights and hotels become more expensive (thanks in part to higher oil prices), businesses are less likely to greenlight travel, and that knocks over another domino that will hurt local retailers.

Another risk is the loss of a financial lifeline. The first day it was available in her Brentwood locations, Roost applied for a Paycheck Protection Program loan. “Without that, we wouldn’t have been able to stay open,” she says. If an even more dangerous new variant emerges or if things take a darker turn in 2022, that type of lifeline is very much in doubt. “Naturally our brains can’t help but think, ‘What will happen next year without that government assistance or any kind of help?’” Roost says. There are countless Vine+Grains with this anxiety. “Mid- and small-size businesses are the heart of everything in Sacramento, and they got hit pretty bad,” says Varshney, adding that many only survived thanks to aid like PPP. “On their own, I’m not sure if they can bounce back as fast or continue to grow.”

As for growth in population? Varshney thinks it’s a mistake to assume that one recent driver of the region’s growth — an influx of 20,000 people from the Bay Area — will continue into 2022. He identifies this as another risk. “People thought that Bay Area migration would go on forever, but that’s going to change,” Varshney says, as technology companies are now looking instead at Texas, Florida, Arizona and Nevada. The overall “pie” of California is shrinking. “We keep thinking that it’s a zero-sum game, or that we are winning because the Bay Area is losing,” Varshney says. “But California has been losing overall. California has issues that are not easily solved.” He ticks them off: homelessness, the high cost of gas and inflation, and concludes that “everything is out of whack.” He says this is why California has a “net migration loss for three years in a row.”

Then there’s the labor shortage — a continuing struggle for Roost. “For everyone, the most limiting factor is going to be access to talent and keeping employees,” Blackwood says. This is especially true in the service sector, as Varshney says the region is overexposed to the service sector “compared to other comparable metropolitan centers,” and is dependent on minimum wage labor, “which in many cases is not coming back.”

The nuance to nuance

Nationally, there’s growing awareness that top-line numbers like the gross domestic product, the unemployment rate or the S&P 500 tell an incomplete story of the economy, and too often they gloss over issues of inequity. This can be true at the regional level. “Things are going to be better. We’re moving in the right direction,” Blackwood says. “But who’s moving in that direction?” That could vary by community. “There’s a new recognition that some of our communities, frankly, have not been invested in, like our rural communities, aging corridor communities, ethnic communities.”

“Things are going to be better. We’re moving in the right direction … But who’s moving in that direction? … There’s a new recognition that some of our communities, frankly, have not been invested in, like our rural communities, aging corridor communities, ethnic communities.”

Amanda Blackwood, CEO, Sacramento Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce

And across all communities, there’s more to the economy than just the number of jobs or the price of a house. To better understand this kind of nuance, earlier in 2021, the Metro Chamber partnered with the UC Davis Graduate School of Management to identify which of Sacramento’s attributes mattered to employees. Blackwood was surprised to find “safety” as the biggest concern, driven by concerns of homelessness, crime and the rise of untreated mental health issues. “When folks’ spending decisions are made on, ‘Do I feel safe walking around at night? Do I feel safe walking to my office?’ The answer is no. That retracts spending, and that retracts the economy. That’s very real.”

Even on the top end of the economic ladder — those seeking six-figure jobs — Varshney spots challenges for the region. “We’re a very service-oriented economy,” he says. So while he imagines there will be plenty of minimum wage jobs available, he’s less optimistic for the upper income bracket. “There are (almost) no jobs coming in that pay a higher wage,” he says, and there’s little upward mobility outside of government and health care. This means that even if we see the overall labor market improve — he expects it will — ultimately, “that does not help explain how the region will evolve over the next five or 10 years to become a more prosperous region.” In other words, a thriving economy needs both lower paying jobs and higher paying jobs. Varshney is concerned that Sacramento only has the former.

Does this mean Varshney is bearish on 2022? Not quite. He clarifies that “2022 will improve over 2021,” for the simple fact that in the aftermath of COVID-19, “our economy will reopen. It doesn’t matter how you slice it, you will still see economic growth and upward movement.” But he worries this obscures the underlying, long-term trends that were issues even pre-COVID-19.

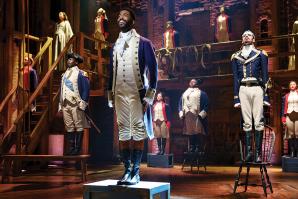

That’s the general consensus: 2022 will be better, yes, but “better” is a relative term. Still, Ault remains optimistic. On a Friday night in November, he walked with his wife on K Street (not far from Vine+Grain) and he marveled at the busy crowds — people at a Sacramento Kings game, people out to see “Hamilton,” people queuing up at restaurants. “It was only two years ago that we were really starting to turn the corner,” Ault says. “And I think there’s a lot of hope and optimism amongst the owners, the retailers and the businesses that we can get back there.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Powering Through the Pandemic

Local governments pull out all the stops to keep their economies rolling

Some solutions Capital Region governments have come up with

will stay around post-pandemic, which could further improve the

business climate.

Sports, Arts and Entertainment Reemerge in the Capital Region

The regional business of entertainment, arts and sports is reemerging with new structures and outlooks in place.

Can Downtown Sacramento Recover From COVID-19?

Downtown Sacramento has been hard hit by COVID-19, stalling its recovery from years of decay. Can it snap back?

The Next Act

Part 6 of our ongoing series on downtown Sacramento businesses dealing with COVID-19

Sacramento businesses continue to adapt and recalculate as COVID-19 evolves.

Holding Pattern

Variety of local businesses shuttered by COVID-19 await reopening

Comstock’s has been following four businesses that have been helping to drive the resurgence of Sacramento’s central city in recent years. Here’s how they’re faring a month into the shutdown.