Uncle Bert seemed normal to me, so I wondered what was going on when a phone call ripped into an otherwise peaceful Monday. It was Dave, a trusted family friend.

“Honey, your uncle has dementia, and all his friends are very concerned about it,” he said. “You need to do something.”

Dave explained carefully. He said my uncle seemed unusually forgetful; he often slurred his speech, became agitated and didn’t carry on fun conversations anymore. He kept telling old stories and repeating himself. He made socially inappropriate remarks; friends were starting to avoid him.

My uncle had been a successful businessman and community leader. People referred to him with appreciation for his assistance to friends and strangers in times of troubles.

Dave told me that if I didn’t do something soon, my uncle’s friends were going to call Adult Protective Services. He explained that patients in the early stages of dementia can hide the condition temporarily and appear healthy during appointments and exams.

I told him I had seen nothing out of the ordinary. Bert had gained weight and was not as convivial as usual; he seemed fatigued and had broken up with his girlfriend a few months earlier. Still, I could not see dementia.

We agreed that as soon as Dave himself saw my uncle in a bad phase, he would call me so I could visit and observe the symptoms myself.

A few days later, my cell phone rang. It was Dave. “Call your uncle, and demand he meet you for dinner,” he said. “Don’t take ‘no’ for an answer. He’s bad tonight.”

This time, at dinner, I saw what Dave was talking about.

I started to place calls to my uncle’s doctors. Then, unexpectedly, my uncle was hospitalized with heart failure. Three days later his insurance carrier transferred him into a convalescent hospital located an hour from his home, family and personal physician. I was surprised to learn that he had given me comprehensive power of attorney, and I was now facing a whole new set of responsibilities, including long-distance caregiving.

Bert’s diagnosis was not straightforward. His doctors said he was having memory lapses and had little concept of personal safety. In addition to the heart failure and some other physical issues, they also determined some cognitive impairment that might be related to his heart condition. But Bert insisted he was entirely well and denied his medical condition.

I soon learned that a man named Jack — an alleged friend of Uncle Bert — had set up what I viewed as a fairly sophisticated strategy to obtain possession of Bert’s money and property and to get my uncle to change the power of attorney designation to Jack.

Jack had befriended my uncle at a conference about five years prior and had slowly gained his trust. Jack was a pretty good handyman and helped my aging uncle with home upkeep while my uncle helped Jack maintain his cars. Bert introduced Jack’s wife, an insurance saleswoman, to prospective clients and helped her build business.

A few years later, Bert had a heart attack, and Jack took the opportunity to convince my uncle to allow him a house key. He then picked up my uncle’s mail, obtained his checkbook and paid the bills while my uncle recuperated.

When Bert recovered and resumed his normal life, Jack spent more time with him. Jack convinced my uncle to tell him where he kept a few valuables, including diamond watches and trust documents. Then, Jack convinced Bert to give him power of attorney over his largest checking account.

Jack expected to assume my uncle’s comprehensive power of attorney. He became angry when he learned Bert had assigned that role to me. Jack had even attempted to discharge my uncle after convincing the hospital staff that he had legal authority over Bert.

Jack was not a stranger to the family, but none of us knew the extent to which he had become involved in my uncle’s life. Bert had always been an independent man, and monitoring his friendships would have been intrusive. Similarly, we would not have expected him to surrender so much control of his life.

If my uncle were suffering from dementia, why couldn’t his physicians make a diagnosis that would allow access to the legal tools that could protect him from such predators? Why couldn’t I demand, with the help of an attorney or law enforcement, that Jack return the property? If Bert had dementia, even in an early stage, couldn’t that stop Jack, or anyone else, from taking property or changing legal documents? My uncle had worked hard as a younger man to position himself to establish and manage his assets. Didn’t he deserve to live this phase of his life with as dignified a quality of life as possible?

The answer, from some perspectives, was “no.”

My uncle’s physicians explained the challenges. Medical tools, standards and procedures were simply insufficient to make the clear diagnosis of dementia that would have given me the tools to protect my uncle. He was in a gray area. He made poor decisions and acted inappropriately at times, but he knew his name and could count to 10.

Bert is typical of an increasing number of aging adults. He has developed some age-related cognitive issues. Because my uncle can often converse intelligently, however, and because he is able to remember names and dates, his doctors were unwilling to make a diagnosis that would lead to the appointment of a conservator.

They told me they feared lawsuits and potential disciplinary procedures if they compromised the patient’s legal rights.

No one denied that Bert was experiencing some degree of cognitive impairment, that he was unable to live alone or that he was vulnerable to predators. In an effort to protect his rights, however, they shut the door on protecting his quality of life and well-being. By protecting him in one way, they were actually setting him up for victimization in another.

In my quest to help Uncle Bert, I have talked with physicians, nurses, attorneys, social workers and other specialists and researchers. They have consistently told me that I have to stay close to my uncle, try to head off any predators and use personal persuasion to ensure he stays out of trouble. When and if his condition progresses so that he is grossly incompetent, I can access standard legal and medical remedies.

Still, I needed support. I found assistance from family members who help with food preparation, medication management, laundry, medical appointments and the innumerable tedious details of elder care. Two of my uncle’s good friends — one a former nursing home administrator and one a retired attorney — call me consistently and help to manage Bert’s circumstances. Their counsel and moral support provide just the right thing at the right time.

I gained assistance from support groups, hospital elder care referral services, community education programs sponsored by the nursing homes and assisted living facilities, caseworkers, senior advisers, attorneys, accountants, nursing home management personnel and other professionals.

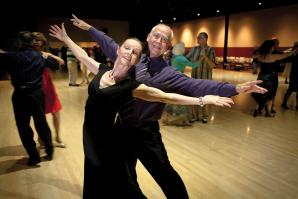

Bert’s situation is not yet resolved. His care has become my full-time job. I hope he can remain content and comfortable as long as possible. In the meantime, I am determined, along with many other professionals and family caregivers, to turn our challenging experiences into greater opportunities to fill the needs of elders and their families. One thing I know for sure: If we can master the dances with deception, we will prevail with policies and practices that transform confusion and vulnerability into clarity and purpose.

A Legal Perspective on Prevention and Solutions

The adage “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” applies as much to elder care as to anything else, and families need to take steps as early as possible to minimize confusion, conflict and potential abuse when their loved ones start to age.

David E. Smith, partner at Kershaw Cutter & Ratinoff LLP emphasizes the importance of establishing communication with “complete transparency, candor and full disclosure” to ensure family members meet the needs and wishes of their elders.

Confusion and opportunities for conflict will be mitigated if everyone understands the family member’s plans and intentions, and if all parties are in the loop. If, for example, grandmother is taken to a medical appointment, her caregiver should then send a group email about the trip, including where they went, who they saw and what follow-up to expect.

Family gatherings provide opportunity for the family member being cared for to state his or her decisions about medical care, financial planning and the allocation of assets.

Preparing legal documents such as a will or trust, designating power of attorney and executors, and completing lists of asset evaluations can help protect elders and provide a standard for decision-making.

“Elders need consistent, ongoing engagement with family members in order to prevent isolation,” says certified elder law attorney Catherine Hughes. Without family involvement, elders can, for example, fall prey to various television or Internet scams. Even senior citizens who have previously been successful in business and who manage the tasks of daily living can become victims of predators.

“Caring family members can often catch subtle and unpredictable signs that their elders may need a little more assistance,” Hughes says.

More specifically, Hughes suggests family members watch the mail for solicitations and sweepstakes offers. A proliferation can provide a telltale sign that their elder responded to an offer and is now a target on growing lists. Family members can also notice abnormal behaviors or new fixations, such as collecting high-priced, poor quality watches, for example.

Potential abuses can typically thrive under cover of secrecy and isolation, but not under the light of openness, transparency and trustworthy family involvement.

— Helen Haig

Recommended For You

The New Old Worker

Seniors enjoy the mental benefits of staying on the job

Americans once looked at early retirement as reward for decades of hard work, a chance to relax and the opportunity to do more of what they enjoyed — including doing absolutely nothing.

Trust Worthy?

Cognitive impairment claims challenge real estate plans

Lesli Pletcher’s parents were not extravagantly wealthy by any stretch of the imagination. However, true to form of a couple raised during the Great Depression, they were frugal and financially cautious so that, by the end of their lives, they had amassed a substantial estate capable of easily sustaining Pletcher’s father in his $9,000-a-month Alzheimer’s care facility.