In the Capital Region and beyond, some customers are switching from large financial institutions to smaller community banks, partially in response to columnist Arianna Huffington’s December 2009 “Move your Money” campaign, which encouraged consumers to do just that. As a result of the initiative, a number of individuals have decided that they want to invest in Main Street rather than Wall Street.

“To a degree, we have seen this,” says George Cook Jr., president and chief loan officer of El Dorado Savings Bank. “There are still some people who associate larger banks with [the Troubled Asset Relief Program].”

Golden Pacific Bank, a subsidiary of Golden Pacific Bancorp. has benefited from the trend. Golden Pacific, among a handful of new lending companies approved by the Federal Reserve this year, opened its branch on 9th and J streets in July 2010. Within 90 days, it had more than $10 million in deposits.

“People are fed up,” says Kirk Dowdell, Golden Pacific’s CEO. “They want to know that decisions are being made locally.”

David Taber, president of American River Bank, says the bank has seen $20 million in new relationships during the first nine months of 2010. The majority of these clients are coming from larger institutions such as Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Bank of the West and US Bank.

Taber compares the idea of banking locally to the movement to buy local foods. “This resonates more with people than it did before,” he says. “Folks understand that doing business locally helps them and their business as well.”

Not all customers are switching to community banks due to Huffington’s campaign. Executives at community banks say a primary reason is that customers want personal service.

“People appreciate a one-on-one relationship,” says Kevin Ardolf, president and CEO of Sutter Community Bank, which opened in June 2006. He mentions that files at the community bank are organized by name rather than number. “Lots of people are intrigued that they can sit down with the CEO of the bank and make a loan.”

Taber says that once someone has a relationship with a smaller community bank, they realize how different it is. For instance, if a client calls the bank, an employee might recognize his or her voice. “People trust us with their hard-earned money, and we work hard to earn that trust,” he says.

Bill Trezza, CEO at the Bank of Agriculture and Commerce, says the bank’s executives get to know customers. “We walk them through their problems,” Trezza says. “Bigger banks used to be this way, but now they’re more focused on efficiency and standardization.” He adds that smaller community banks are involved in civic boards and are also part of the community through groups such as Little League Baseball. “It’s difficult for larger banks to be that involved in the community.”

River City Bank has also seen customers moving from larger banks. Steve Fleming, River City’s president and CEO, says its most fertile ground for new customers is the pool of former jumbo-bank patrons. “It boils down to [customers] being more important to us and, therefore, getting more attention,” Fleming says. “There’s more access to the decision-makers of the bank who live in the community.”

One of the newcomers at River City is John Webre, president of Dreyfuss and Blackford Architects, who switched from a much larger bank last year. Webre decided River City could provide a customized solution to the architectural firm’s cash management needs, and he was confident it would be a safe place to keep money. Later, Webre asked River City for a line of credit, which he describes as “very competitive.”

Webre says Fleming has invited him to CEO-sponsored roundtables where they discuss the challenges facing businesses. “It’s way more high-touch than a Bank of America or Wells Fargo,” Webre says. “I feel handled.” River City bank has also invited him to events such as customer appreciation parties. “Bigger banks couldn’t have a connection like River City can.”

Mark Hoag, president of United Corporate Furnishings Inc., switched to River City this fall and says his company had a generally positive relationship with its previous large bank, but thought it was time to investigate other options.

After an initial meeting with River City, a cross section of the bank’s team visited Hoag’s office. Then, after a number of follow-up phone calls, River City presented him with a proposal. “We were impressed by River City Bank’s flexibility and their tailor-made response,” Hoag says. “I attribute much of this to their ability to make decisions locally.”

Smaller banks also say they are better at customizing business loans than larger banks. Dowdell says there is a tremendous backlog of qualified customers who the bank can serve. “It’s hard to get a loan from a big bank,” he says. “You need to fit all their criteria. Most businesses and individuals need some customization.” Dowdell adds that smaller institutions can also move faster than larger money center banks. “If a business needs to close on a transaction in two weeks, Golden Pacific can do it quickly.”

Despite an influx of at least some new customers, challenges remain for small community banks. In August 2010 the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. identified 829 “problem” institutions nationwide, up from 775 in March 2010, many of which were smaller banks. Whereas large national banks tend to have diverse loan portfolios, some smaller financial institutions have significant exposure to commercial real estate loans. Moreover, in August 2010 Thomas Hoenig, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, warned that the perception that larger banks are “too big to fail” may put smaller banks at a competitive disadvantage.

In the Capital Region, banks have seen an increase in competition for a handful of highly qualified borrowers who meet lending institutions’ underwriting liquidity requirements. Banks are fighting over this smaller piece of the pie. Some credit unions are making small business loans, and insurance companies are becoming more active in commercial real estate lending.

Even though community banks may be seeing some new clients, people aren’t borrowing money. John Primasing, chief credit officer at the Bank of Stockton, says two things are happening. “You’ve got fewer qualified customers, and those customers don’t want to borrow,” he says. “Everyone is sitting on the sidelines.”

Kathie Sowa, national small-business credit executive for Bank of America, says the bank is seeing increased competition, but mostly at the larger end of the business segment. “Banks have lots of capital to lend, but there are fewer qualified borrowers,” she says. The basic standards of lending remain the same, Sowa says, but a highly competitive environment can lead to more negotiation in such areas as loan structure and covenants. In addition, in late 2010 and throughout 2011 Bank of America plans to hire 1,000 small-â?¨business bankers nationwide to address the needs of local businesses. Another benefit of this initiative will be the creation of jobs in communities across the country.

“Things are still pretty tight in this region,” says Bill Martin, CEO at the Bank of Sacramento. “Business borrowing demands are way off. We’re not seeing the requests that we used to.” Martin says that although the bank has seen some movement of customers to the bank, there hasn’t been a mass exodus from large banks. “Businesses are reluctant to move anywhere because there is so much uncertainty.”

Larger banks in the Sacramento area say they have not noticed a trend in borrowers or small businesses leaving for smaller banks. Sowa says they have actually seen an increase in deposits at Bank of America. Randy Reynoso, business banking division manager for Wells Fargo in Northern and Central California, says the bank’s business deposits have remained stable and in most areas grown year over year. Reynoso, who was the former president of Placer Sierra Bank before it was acquired by Wells Fargo in 2007, says in many ways Wells Fargo acts much like a community bank. “We have local decision making,” he says. “We really try to out-local the national banks and out-national the locals.”

Reynoso points out that Wells Fargo can offer business customers a one-stop approach, including new technologies such as remote deposit. Some community banks might not offer such services, he says. Reynoso says Wells Fargo also offers treasury management tools such as fraud detection. “That’s great technology, which we didn’t have at our small community bank,” he says.

However, proponents of community banks say they are catching up with larger financial institutions when it comes to offering the latest technologies. “In some cases, we can do it sooner and faster at community banks,” says Nancy Sheppard, president of trade association Western Independent Bankers. For instance, the Bank of Stockton was one of the first banks in the West to have mobile banking, which allows customers access to bank accounts through their cell phones.

Individuals at community banks do say, however, that they can’t do everything for everyone. For example, Dowdell points out that there are capital constraints. If a business needed a $15 million loan, most community banks would be out of the picture. “We do a better job serving the small-business customer,” he says.

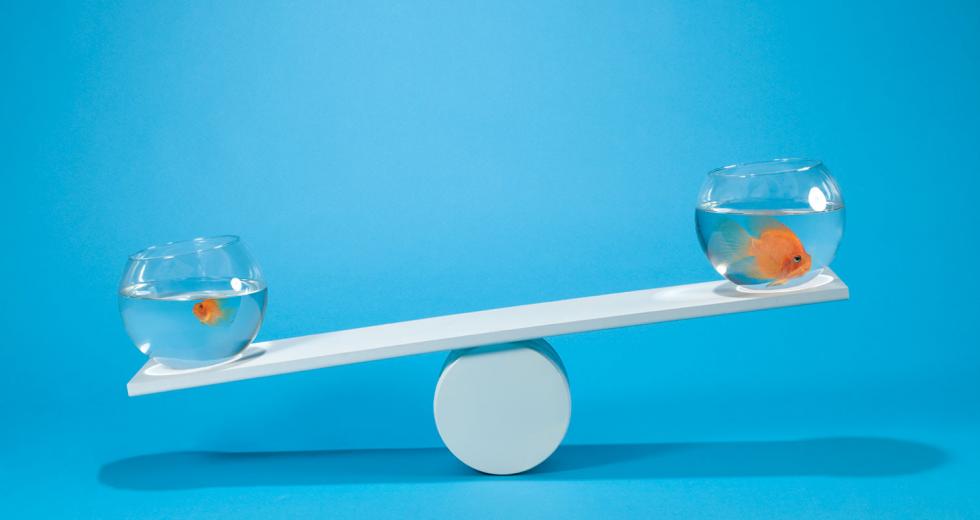

Executives at community banks say one obstacle right now is the public’s overall perception of banks. Trezza says the media gives people the idea that “banks are banks.” However, community bankers point out big differences between Wall Street and Main Street. For example, they say, local banks channel more loans back into depositors’ neighborhoods.

“The greatest challenge is letting people know that there are alternatives to Wells Fargo, Bank of America, etc.,” Dowdell says.

Western Independent Bankers started a campaign in April to raise awareness about community banks. The website ibanklocal.org describes what community banks are and how to find a local bank branch in your area. Western Independent Bankers also ran radio ads in the San Francisco Bay Area. “We did see some movement and good reactions as a result,” she says. Western Independent Bankers is currently raising money from local banks for a similar radio campaign in the Capital Region.

“The whole idea is differentiating Main Street banks from the definition of banks being bandied around by the press,” Sheppard says. “We decided it was time to hold our heads high and say, ‘We’re not what you hate.’” She says although a few small banks were involved in subprime lending, most were not. “Big banks are not all bad, but they’re not really integral in their communities in the same way as community banks.”

Recommended For You

Merge or Purge

Community banks contemplate consolidation as regulatory costs grow

Banks throughout the country are putting new practices in place to comply with an onset of new federal regulations prompted by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and other post-meltdown rule changes. Those expensive efforts are sparking major changes and concerns for some of the Capital Region’s smaller lenders.

The Big Squeeze on Small Credit Unions

They may be on the verge of extinction

On a hot, sunny morning last fall, 69-year-old retiree Pamela Chappell of Citrus Heights hit rock bottom. She was scraping by on Social Security checks and a tiny pension while paying for medication to treat her lymphedema, a painful swelling in her legs. Then she got a letter from the IRS warning her that it was about to empty her savings account of $8,000 — every dollar she had — for back taxes.