The message popped into UC Berkeley sophomore Varsha Sarveshwar’s inbox a few days before the start of her Introduction to General Astronomy course in the fall of her freshman year. It contained the usual details about class times and textbooks. But then there was something surprising: a plea from the professor to skip the first day of class.

Related: California Campuses Confront A Growing Challenge: Homeless Students

Related: Why a Dearth of Latino Professors Matters

“I’d like to encourage at least 200 of you NOT to come to Hertz Hall the first two lectures, and simply watch them on webcast instead,” professor Alex Filippenko wrote.

While 850 students were enrolled in the course, the lecture hall could only hold 650, Filippenko explained. The fire marshal might shut down the class if too many people attended.

The message from Filippenko—a celebrated astrophysicist whose popular course also satisfies a graduation requirement—illustrates the challenges the University of California faces as it squeezes growing numbers of students onto overcrowded campuses with deteriorating buildings and equipment. Over the past two decades, as state funding for higher education declined, California’s public research university increased class sizes, sometimes failed to maintain basic infrastructure like roofs and cooling systems, and put off construction projects—even as it enrolled an additional 90,000 students.

The result is a deferred maintenance backlog that UC estimates at $4 billion and fears among faculty and administrators that the system, once the envy of the rest of the country, is beginning to lose its luster.

“It has a growing impact,” UC President Janet Napolitano told CALmatters. “We need the state to reinvest in the university. We need to be able to have new labs. We need to be able to refresh the labs we have.”

Gov. Jerry Brown seemed to hear her plea on Friday when he added to his proposed 2018-19 budget a one-time infusion of $100 million each for UC and California State University to make campus repairs. The funds are part of a larger effort to upgrade the state’s ailing infrastructure. But they will only cover a fraction of the backlog and don’t account for the university’s long-term need for new buildings.

“He’s proposing a Band-Aid on a massive capital deficit wound,” said state Sen. Steve Glazer, an Orinda Democrat who wants to put a proposition on the November ballot asking voters to support $4 billion in bond funding for the two universities to build classrooms and labs.

At UC’s Grad Slam competition May 3, top graduate students from each of the university’s 10 campuses faced off to see who could best explain their research in three minutes or less.

Kimberley Kanani Bitterwolf, the UC Santa Cruz finalist, studies the chemistry of rivers and groundwater to understand how the earth’s climate has changed over time. Her research could prove helpful in predicting the effects of global warming—but she’s had to conduct much of it in Germany, because UC Santa Cruz lacked the pricey equipment she needs.

When she’s in Santa Cruz, Bitterwolf said, she makes the hour-long drive to a San Jose non-profit that collects donated equipment from biotech companies, picking up pipette tips and other supplies that she can’t get on campus.

Broken, leaking, and unusable bathrooms are not an uncommon sight

for students at UC Riverside. Photo by James Bernal for

CALmatters

“I call it thrifting for science,” she said.

Other students, faculty and administrators from multiple UC campuses described sweltering classrooms and leaky labs.

“The building I work in needs a roof and it actually rains inside the building,” said Frances Leslie, dean of the graduate division at UC Irvine and a pharmacologist who studies how tobacco use affects the brain. “That’s not good for research and it’s not good for students.”

Just how bad the problem is has been difficult to quantify. UC professors still conduct cutting-edge research in state-of-the-art laboratories, but those exist side by side with outdated and neglected buildings. Resources vary widely among campuses and departments, with some of the most popular and prestigious programs hit hard by overcrowding.

The university is spending $15 million to send a team of experts to assess the condition of facilities on each campus, a study that won’t be complete until 2021.

Why so lengthy and costly? It’s an “ambitious project that includes not only having someone visually assess every square foot of UC buildings and infrastructure but using that information to make reliable, consistent estimates of both current and future needs,” UC spokeswoman Claire Doan replied in an email. She added that it would produce a deferred maintenance forecast for about 64 million square feet of state-supported space.

While the state is flush with cash from higher-than-expected tax revenues, Brown has repeatedly warned of a coming recession. Instead of adding to California’s ongoing expenses, he wants to spend part of the $9 billion surplus on one-time projects and sock the rest away in the state’s rainy day fund.

At a press conference announcing the governor’s revised budget proposal, his finance director, Michael Cohen, said the new infrastructure spending was “an acknowledgement that we have not done well as a state in keeping up with our maintenance needs.”

“This is what we can afford right now to try to chip away at that,” he said.

UC Riverside is among University of California campuses in need

of repairs and upgrades. Photo by James Bernal for CALmatters

The Legislature could vote by June on whether to put a higher education bond on the ballot. The last time that happened was 2006. In a poll conducted by the Public Policy Institute of California last year, a majority of likely voters said they’d vote yes on such a measure.

Part of the challenge is figuring out just how much enrollment at UC should grow. A growing number of California’s high school graduates meet the eligibility requirements to attend. Add in a new agreement designed to boost the number of transfers from community colleges, and the university could face a tidal wave of incoming students that it’s ill-equipped to accommodate.

UC spends only about half of what comparable public research universities do on maintaining its campuses, a recent PPIC analysis found. Spending plunged in 2010 and has not bounced back.

Private donations can help fund marquee projects like a new performing arts center, or profit-sharing ventures like a parking garage. But the less-glamorous task of building and maintaining classrooms usually requires public dollars, said Patrick Murphy, a senior fellow at PPIC who studies capital spending in higher education.

“No one’s lining up to put their plaque on the air conditioning unit,” Murphy said.

The effects can be seen on campuses such as UC Davis, where students say they sometimes sweat their way through classes in rooms that lack working air conditioning.

“Having to teach in those spaces is hugely uncomfortable,” said graduate student association president Roy Taggueg, adding that temperatures during spring finals week often climb into the 90s.

Fourth-year student Alondra Cruz said it was so hot in her Mexican-American history class that the professor converted the midterm and final to take-home exams so students could concentrate. “At times I would be sweating so much that I’d be focused on that and not on the lecture,” she said.

As enrollment grew by more than 20 percent over the last decade, the campus has commandeered an exercise room and even a theater to use for classes. “It works pretty well, except depending on what sort of performances are happening, the instructor doesn’t know what’s going to be set up on the stage,” said Kelly Ratliff, the campus’s vice chancellor for operations.

Ratliff said UC Davis has found creative ways to finance new classroom space, sandwiching it into projects funded by private donations, such as the new Manetti Shrem Museum of Art. Each winter, as rainwater leaks into the nearly 50-year-old Briggs Hall, campus officials strategize about how to protect the delicate biological experiments taking place there. A reroofing project is in progress, but it’s unclear when the university will be able to complete it.

“Plugging a hole isn’t the same thing as solving the problem,” Ratliff said. “But without a full funding model, more often than we’d like, we’re just plugging the hole.”

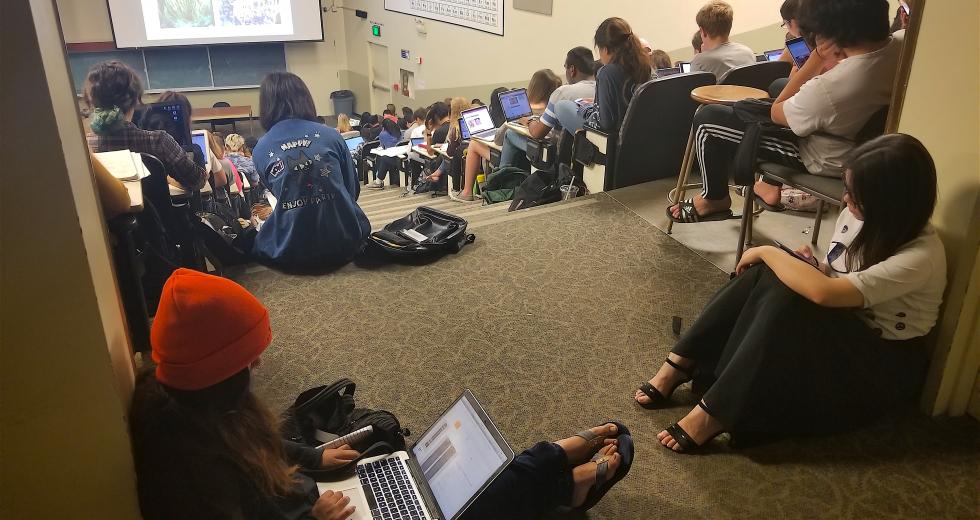

At UC Riverside, second-year student Emelia Martinez said it’s common for classes to have dozens of students standing or huddled on the floor because there are no seats available.

“These are students that are paying tuition, and they are sitting on the floor,” Martinez said. “We really can’t continue like this.”

Lower-division class sizes have increased slowly but steadily systemwide since 2006, UC officials say. UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ told the university’s board of regents in January that lower-division lectures in the electrical engineering and computer science department had ballooned from an average of 65 students in the 2011-2012 school year to 227 in 2016-17.

The state’s Legislative Analyst reported that some of UC’s existing classrooms are underused, although student leaders insist that’s because rooms on older campuses like Berkeley and UCLA can be too small for today’s class sizes.

The university plans to build new classrooms at UC Davis and Riverside beginning this year, plus make seismic safety improvements to buildings at UCSF and UC Berkeley—both of which sit on or near major fault lines. UC can finance construction using its regular budget allocation from the state, which Brown has proposed boosting by 3 percent. University officials say that’s not enough, and are asking for another $105 million to cope with growing enrollment and avoid raising tuition.

While dozens of legislators have pledged their support for the request, others are wary after a state audit last year found Napolitano’s office had kept $175 million in reserve funds hidden from the public. The university came under further pressure last week when tens of thousands of campus service workers walked off the job in protest of outsourcing and what they described as racial and gender pay inequities among workers.

“As legislators, it’s difficult for us to decide on a budget package for the University of California as UC administrators impose such harsh terms on its lowest-paid frontline workers,” Assembly Appropriations Committee chair Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher wrote in a pointed letter to UC just before the strike.

Of course, overcrowding is not just an issue of physical space: Campuses also need enough professors and teaching assistants to cover rising demand, especially in popular departments. But faculty and administrators say the two issues are linked.

“We want to recruit the very best minds from California and across the world,” said Carol Genetti, dean of graduate studies at UC Santa Barbara. But top students, she said, are looking for a graduate school that can offer them high-quality facilities and generous stipends. “When they come to visit campus, if we can’t show them that we can do that, we’re at a significant disadvantage.”

Filippenko, the UC Berkeley astronomy professor, said he intentionally over-enrolls his classes to help students who are desperate to meet graduation requirements. When the observatory where he and his students perform research was threatened with closure, he organized to save it, helping to win a partial reprieve.

A former Guggenheim fellow and member of the National Academy of Sciences, Filippenko said he’s received job offers from elite universities where he’d have more telescope time and a smaller teaching load.

“I stay in part because I so firmly believe that we need a great public university,” he said. “People need to take the long view and support this amazing system that we have.”

CALmatters’ Laurel Rosenhall contributed reporting. This story and other higher education coverage are supported by the College Futures Foundation.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.