High school seniors across the state are waiting on news that will shape the rest of their lives.

This spring they find out whether they are among the thousands being admitted to the University of California or California State University.

Related: A Community College Online?

Related: Why a Dearth of Latino Professors Matters

Both UCs and CSUs are struggling to find space for qualified residents at overcrowded campuses, and tens of thousands of eligible students will be turned away. If they leave the state for college, and don’t come back, it could be trouble for the state’s economy.

This year, marking the 150th anniversary of the University of California, President Janet Napolitano laid out steps to meet growing demand. She called on chancellors to graduate more students in four years, clearing the way for new students, and advocated for a policy that would guarantee admission to qualified community college transfer students.

Meanwhile, this week CSU trustees approved policy changes to redirect eligible applicants to campuses with space, instead of rejecting them outright. The changes go into effect for fall 2019 applicants.

But as California’s public universities scramble to accommodate more students, nearby out-of-state schools are welcoming them with open arms.

Two years ago, Danny Holton was the one waiting. He was a senior at Mountain View High School, in the heart of California’s tech mecca.

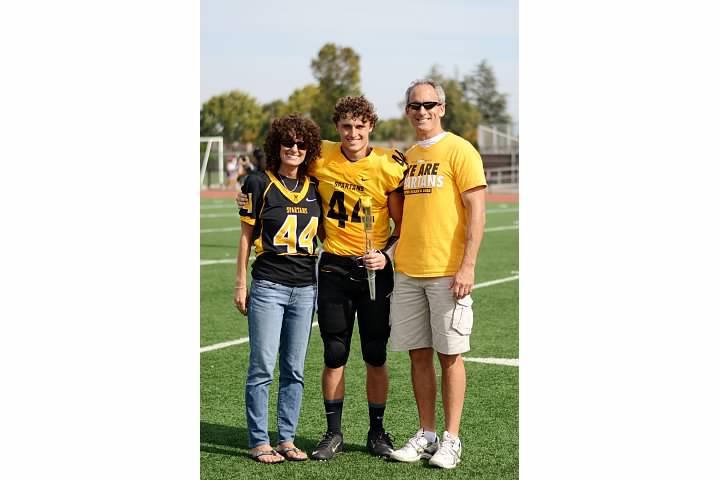

Danny Holton with his mom and dad, Carolyn and John, at a high

school football game. Photo courtesy Danny Holton.

He had a 3.85 GPA. It wasn’t the 4.6 some of his classmates had, but still, he felt good about his prospects, and lucky to be in California. “I grew up in a place where there are all these great schools just hours away,” he says. “Other states don’t have this opportunity just laid out.”

Holton loved how friendly people were at his top pick, CalPoly San Luis Obispo. He also liked the UC campuses in Davis, San Diego and Irvine with their big green spaces where students studied in the sunshine. He was excited to turn in his applications. “You know, my whole high school career kind of led up to this point, you know, getting the acceptance letters from CalPoly, the UCs.”

When the letters started coming in it was bad news. “They just kept coming. It was like the same letter, San Diego Davis, Irvine: We regret to inform you that we won’t let you in.” CalPoly didn’t let him in either. “No wait list,” Holton says, “It felt like I wasn’t even close.”

It’s become a common story. Last year, the CSU system turned away more than 30,000 eligible students. In 2017, UC turned more than 10,000 eligible applicants away from their schools of choice, instead referring them to the only campus that has room to grow: UC Merced. 124 of those students say they plan to enroll there.

As California’s population grows, and increasing numbers of high school grads meet college eligibility requirements, ever more qualified CSU and UC applicants have to compete for limited space, according to experts at the Public Policy Institute of California, who say the problem is compounded by a long-term trend toward declining state investment. PPIC data shows in 1976–77, higher ed spending made up 18 percent of the state budget, but by 2016–17 it had fallen to 12 percent of the budget.

While California’s demographics have changed, its propensity for growth hasn’t.“One of the main themes in California history is constant population growth,” says John Douglass, a research fellow at UC Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education and author of “The California Idea and American Higher Education.”

The difference now, he argues, is a lack of vision. The feat of California’s famed 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education was not that it established an accessible high-quality college system – that already existed — but that it secured that promise for the future. “The great legacy of the Master Plan was an agreement about how the system should grow, what campuses should be developed, and what kind of money would be involved,” Douglass says.

Danny Holton says he was a good student in high school. He was in

AP classes, involved in school clubs, sports and activities. Here

he is as homecoming royalty his senior year. Photo courtesy Danny

Holton

It was supposed to be a plan through 1975, but the state hasn’t come up with an alternative. “We’re living off of infrastructure and an investment by the state that’s 50 years old,” he says.

So what students like Holton are experiencing is in part the result of a failure to adequately plan for the boom in college-eligible high school grads, Douglass says.“We don’t have anybody doing any long term enrollment studies as of now, so we need a lot of homework to be done.”

As Holton’s rejection letters piled up, he was grateful he had a backup plan. His college counselor had urged him to apply to a few out-of-state schools, and the news from outside California was better.

“When I got my acceptance from ASU (Arizona State University), that was awesome,” Holton says. He even got a certificate with his name on it, signed by the dean welcoming him to the undergraduate business school.

Not only did Arizona State University welcome Holton, they offered him $54,000, or about half his tuition for four years.

Holton was placed on the waitlist at UC Santa Cruz and eventually admitted. But that was not until the summer, long after he had accepted admission to ASU.

The decision to leave the state for college is one a growing number of California families are making. Since 2002, Arizona State University has seen an increase of more than 200 percent in California student enrollment. At Oregon State University, California freshmen made up 3 percent of the incoming class in 2002. By 2017, California freshmen made up nearly 14 percent of Oregon State’s new students.

The last available U.S. Department of Education data, from 2014, shows more than 36,000 California freshman enrolled at out-of-state schools.

Those statistics trouble Lande Ajose, executive director of California Competes, an organization that advocates for higher education policies that increase access. “Those are bright and talented students,” she says. “Those are students whose families are here in the state. Those are students who then may or may not return home.”

Holton is glad he went to ASU. He likes his classes, he got a good internship. He has another two years of college to decide what he’ll do next, but the longer he stays in Arizona, the harder it gets to leave. “I just have the connections here,” he says. “This is where I am now. I’d call it my home.”

If Californians like Holton don’t come back, analysts warn the state is headed for trouble. The PPIC estimates by 2030 nearly 40 percent of the jobs here will require at least a bachelor’s degree, and state universities just aren’t turning out nearly enough of them. The institute projects the state will be over a million workers with bachelor’s degrees short of economic demand by then.

“Without a focus on how we’re going to move kids through,” Ajose says, “we’re leaving industries at risk of not being able to find the talent that they need to have.”

And she points out it’s not just about the economy. Studies have shown college graduates are more likely to be engaged in civic activities like voting and volunteering. “It also matters for the kinds of communities we want to live in,” Ajose says.

There is work being done on campuses and at the State Legislature to address the bleak forecast. Lawmakers mandated UC increase enrollment by 10,000 in-state students over three years, a target the system has already surpassed. CSU’s Graduation Initiative 2025 aims to help students graduate on time, freeing up more space for new students, and there are signs it’s working: for 2016-17, 99,000 CSU undergrads earned degrees — almost 7,000 more than the year before, and a record high.

But experts warn more will need to be done if California is going to live up to the promise of access that created one of the greatest higher education systems in the world. “Without a significant increase in the enrollment and academic program capacity,” Douglass says, “Californians can’t expect to continue to have the access rates they have today, let alone yesterday.”

The California Dream series is a statewide media collaboration of CALmatters, KPBS, KPCC, KQED and Capital Public Radio with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the James Irvine Foundation.

Recommended For You

3 Social Media Tips for Your College-Bound Teen

Start networking early by leveraging online tools

Try these three strategies to help teenagers use their social media platforms to better prepare for college.

Hard Times at For-Profit U

If the for-profit college model fails, where will the students go?

When Chris Treiber left the Navy in 2011, he set sail on uncharted waters. His 10 years of service offered no natural path into a good job. He’d spent his last five of those guarding prisoners and had no civilian job experience. He had a GED, having dropped out of high school in 10th grade. And at age 32, he had a wife and five kids to provide for.