In the week since California began shutting down for the coronavirus crisis, Elena Ramirez has spent her days deep cleaning at her Happy Face Family Preschool. Her doors have remained open, even though none of the 14 kids she usually cares for in San Francisco’s Sunnyside district have shown up for a week now and both her teachers have stopped coming to work.

Now with the statewide order, issued late Thursday by Gov. Gavin Newsom, for California to shelter in place — except for essential workers — Ramirez is at the ready for kids, especially those of first responders and health care workers that county agencies might send her way.

Click here for more coronavirus coverage

How long she can hold out, however, is to be determined. Her budget is tight. She has a mortgage. And while the state, she is told, will continue to pay for the kids in her charge who are eligible for subsidized child care, regardless of attendance, it’s unclear if the families who pay out of pocket will do so.

“If they don’t come back it’s going to be economically devastating for me,” said Ramirez, noting that it could be emotionally devastating as well: She’s been hoping she won’t have to enforce contracts requiring families to pay even for days their children are absent. But times could get tough.

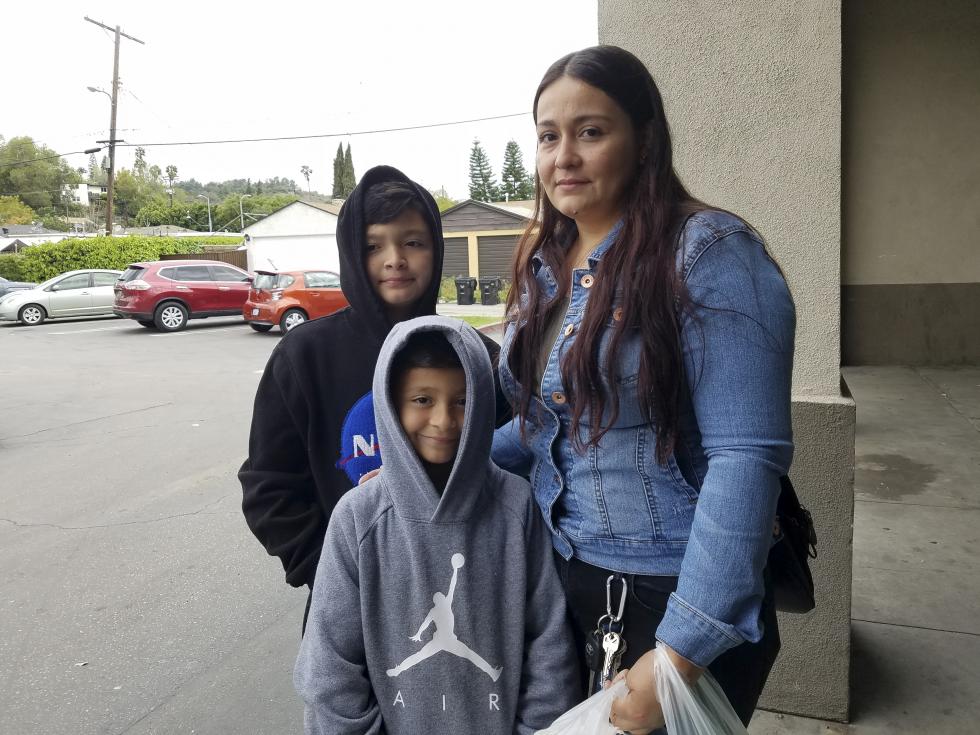

Jeannette Nestor’s two sons Jason, 11, and Jacob, 7, are at home

with her since school has been canceled, and the two babies she

usually watches are with their parents, who have experienced job

cutbacks. (Photo by Elizabeth Aguilera for CalMatters)

“I’m a mother of two college students and my husband is retired,” she said. “My income is the main income we have.”

As schools, businesses, governments and most other venues go increasingly dark in the effort to restrict the pandemic, one question has persisted: What to do about child care?

While some facilities have closed on their own, state and local officials have stopped short of ordering the closure of early child care centers, daycare sites and preschool, focusing instead on back up child care for doctors, nurses, first responders and other essential workers, such as — suddenly — grocers and delivery drivers. It has been a tough choice: The emergency response to coronavirus is relying on humans refraining from contact, and if there is one aspect of child care that is a constant, it is touching.

But, Newsom said in a recent address, “We need our child care facilities, our daycare centers, to operate to absorb the impact of these school closures.” So, for the moment, he added, “we are not calling for all daycare centers in California to shut down.”

How will that work? With much disinfectant and washing of tiny hands, for one thing, according to state guidance. And if a flu or coronavirus outbreak occurs in the area, a child care center may have to shut down for a month or more anyway.

Operators who remain open will have to follow a checklist that includes creating a plan for the pandemic, assigning staff to monitor public health announcements, identifying how a pandemic can affect their program, identifying staff to supervise hand washing and ensuring sick workers stay home and encouraging families to have a backup plan for care.

California has 10,770 child care centers and 25,940 family day care sites, which account for the care of nearly 1 million of California’s littlest kids, according to statistics from Kids Data, a Palo Alto-based clearinghouse for child health information. Many more children are minded in ones and twos by friends or family members who are not required to apply for a license.

So far, of the state’s 1,006 positive cases of coronavirus, 18 have been kids 17 and under. The state has not released the specific ages of the children or how they transmitted the infection.

Happy Face Family Preschool director/owner Elena Ramirez at the

door of her daycare, which she runs out of the basement of her

San Francisco home. (Photo by Anne Wernikoff for CalMatters)

Los Angeles County is going further with its child care guidance, allowing centers to stay open to care for the kids of essential workers with no other child care options but with caveats. Child care centers are required to keep kids in groups of 12 or fewer and not mingle with other groups of children. Operators are also required to take the temperature of kids as they arrive, focus on play that minimizes sharing toys, and encourage parents to create a backup plan for care.

Parents who are at home and can keep their little ones with them should be doing so, said Barbara Ferrer, director of the Los Angeles County Dept. of Public Health. This strategy is intended to lower the number of children at centers to allow more social distancing.

It’s also to keep options open for health care workers and first responders, Ferrer added:“There could be a time when we could close them, and then work with essential workers to find a place to care for their children.”

That’s what San Francisco is doing for school-aged children. It opened child care centers in libraries and recreation centers for the children of essential workers after schools closed.

Other states are already clamping down on child care centers. In Vermont, the governor has closed all child care centers except those that care for the children of essential personnel. The centers that do stay open have to follow new guidelines including a 10-child limit in each classroom.

Children have not been as widely impacted as adults by the virus but that doesn’t mean they can’t get it — and spread it to grandparents and other at-risk populations, said Dr. Ilan Shapiro, medical director of health and wellness for Altamed and a pediatrician. “The virus needs humans to jump from one to another and they are the perfect vector,” said Shapiro. “If we have that exposure it’s like adding gasoline to a pile of perfectly dry wood.”

Child care advocates say they need the state to help them financially with funding for backup teachers and for benefits such as unemployment insurance. Petitions have been organized by Child Care Providers United and Californians for Quality Early Learning.

“The strain being placed on our child care providers, who are already operating on razor thin margins, could force many of them out of the business permanently,” tweeted Sarah Rittling, executive director of First Five Years Fund, which lobbies for equal access to child care and education.

The Fund is calling for Congress to include child care providers in its economic stimulus package. A recent survey by The National Association for the Education of Young Children found that more than 60% of child care centers could not financially survive being closed for one month.

Clara Sibley, 4, rides a scooter past her closed preschool while

her dad Dean Sibley walks with her in Sierra Madre. (Photo by

Elizabeth Aguilera for CalMatters)

As the pandemic has set in, some California centers have closed, mirroring K-12 school closures. Others have vowed to remain open as long as their charges show up.

Samantha Logolusa, who owns Growing Patch Private Preschool in Fresno, said that unless the government shuts her down, she will stay in business. Her daily attendance has gone from about 60 to 25 children.

“It’s important for my families to stay open because I know they need the child care,” said Logolusa, who has 12 employees. “For me, it’s more important for my employees who need the money. If I close they don’t get paid.”

Child care workers affirm that their financial security is a worry. Ayse Inceoglu, a preschool worker in Long Beach, for instance, said that after she came down with a cough, she was told to quarantine at home for two weeks.

“My job doesn’t pay for that period of time,” she wrote in a message from quarantine. “I am diabetic and have health conditions and I’m worried about this,” she said. “I am a single mom and I have an 18-year-old son and I pay the bills.”

Jeannette Nestor is also concerned about finances since the two babies she usually watches are now at home with their parents, whose jobs were cut back. Her sons, 11 and 7, are both out of school for the indefinite future, and last week her husband, a construction worker, went to Mexico to interview for a green card. It’s unclear when he will return, she said, and she fears he’ll get stuck there.

“That would really hurt us because he’s the main provider and we have a mortgage and bills,” she said. “I asked him to cancel but he has been waiting four years for this interview.”

Families juggling work and children — whether because of closures, finances or fear of the virus — are worried, too.

Lisa Lipps is sheltering in place with an 11-month-old baby and a preschooler. The salon where she is a stylist closed for two weeks and her husband, who works at a local utility, is considered an essential worker. And both her older daughter’s preschool and her younger daughter’s daycare are closed.

The preschool is offering a credit while the school is shuttered, but the daycare is requiring families to pay to keep their slot open. “We should not be charged for a service we are not able to access,” Lipps argued.

Yet without childcare she can’t return to work if the salon reopens. “That’s why I think I’m a little frantic and in panic mode,” Lipps said.

In Los Angeles, Rachel Steinhardt, her husband and a college-aged nanny are sharing child care for their 2- and 5-year-old sons. Their early childhood center closed for a month.

“I’m really nervous about a shelter in place order because our nanny won’t be able to come,” said Steinhardt, approving a request to watch one more episode of a Lego cartoon show. “That is my number one concern.”

Jamie Spyra, whose 3-year-old has been one of a few kids at his Venice daycare this week, isn’t sure what to do under the new order. She and her husband are working from home and the three days their son goes to the family-based center are helping.

“Since there are only three kids there I feel fine with him going but if more kids come back I don’t know, because I’m pregnant and I’m high risk,” said Spyra, who works for a clothing brand. “Unless something drastic happens they are planning on staying open.”

In Sierra Madre, Dean Sibley followed his 4-year-old daughter Clara as she rode her scooter on the sidewalk past her closed preschool.

Sibley thinks the closures are an overreaction to an illness he likens to the flu. But for now, the grounded corporate pilot is hanging out with his four kids at home — a college student, a homeschooled high schooler, a grade schooler doing distance learning online and Clara. She said she doesn’t miss much at her preschool except “the slide.”

–

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.