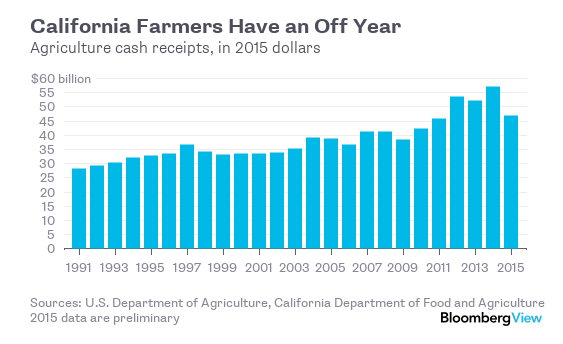

California agriculture, which had been plowing ahead in the face of a major drought, finally had an off year in 2015, according to data released recently by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The state’s farms brought in cash receipts of an estimated $47.1 billion (this will be revised in the months and years to come), down from a record $56.6 billion in 2014. Here’s how that looks in historical context, with the numbers adjusted for inflation.

Why should you care about this, if you’re not a California farmer? Well, California is the country’s leading agricultural producer, by far. (Iowa was No. 2 in 2015, with cash receipts of $27.8 billion.) It is also the most populous state, with an economy that would rank as the world’s sixth largest (behind the U.K., ahead of France; although it’s lower if you go by purchasing-power parity) if it were an independent nation.

California also has, as you may have heard, some chronic water-supply issues that may be getting worse as climate change affects weather patterns and reduces the Sierra Nevada snowpack that has always acted as the state’s biggest reservoir. Agriculture accounts for about 80 percent of the state’s water use, and I think it’s fair to say that the consensus among those who think hard about these things (including farmers) is that this percentage will have to go down for the state to continue to survive and thrive. Improved efficiency can take care of some of this, but it also seems inevitable that there will have to be a bit less farming done. Low-value crops that could easily be grown in other states — alfalfa, say — are an obvious target for many observers.

So was the 2015 drop in agricultural receipts a sign that California’s farmers are actually pulling back? Definitely, somewhat — a federal-state study found that farmers in the state’s Central Valley left 522,000 more acres (about 7 percent of the state’s irrigated farmland) unplanted in the drought summer of 2015 than in the last above-average rain year, 2011. But a closer look at the 2015 crop statistics for California’s top farm counties still leaves an observer (me) astounded at how little impact the drought had on production.

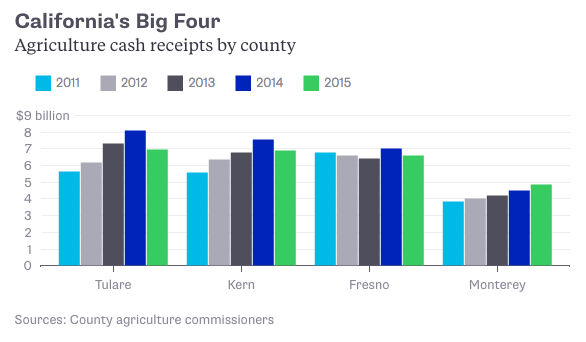

Fresno County is the outlier here, with agricultural receipts that actually fell from $6.8 billion in 2011 to $6.6 billion in 2015. Which makes sense: It is home to the Westlands Water District, a vast, controversial and currently struggling expanse on the west side of the county that is heavily dependent on water from the federal Central Valley Project, which delivered nary a gallon to Westlands farmers in 2014 and 2015. But the other three counties all had substantially higher receipts in dry 2015 than wet 2011 (and while the numbers in the above chart aren’t adjusted for inflation, that would still be true if they were).

Tulare and Kern counties did see drop-offs from 2014 to 2015, but this appeared to have at least as much to do with falling prices for milk (Tulare County’s No. 1 agricultural product and Kern County’s No. 4) as with drought-related cutbacks. And Monterey County, which specializes in a lot of the crops most identified with California agriculture — its top three are lettuce, strawberries and broccoli — has just kept setting new agricultural production records every year.

None of these places had any gushers of water flowing its way. Tulare and Kern counties, both in the Central Valley to the south of Fresno County, were mostly cut off from state and federal water deliveries in 2014 and 2015, and Monterey County never gets them because it’s on the other side of a range of mountains from the aqueducts through which the water flows. Farmers in all three counties had to rely on a few not-very-full local reservoirs and groundwater. So they pumped, and pumped. (Something that, because of salinity issues, many Westlands farmers aren’t able to do.)

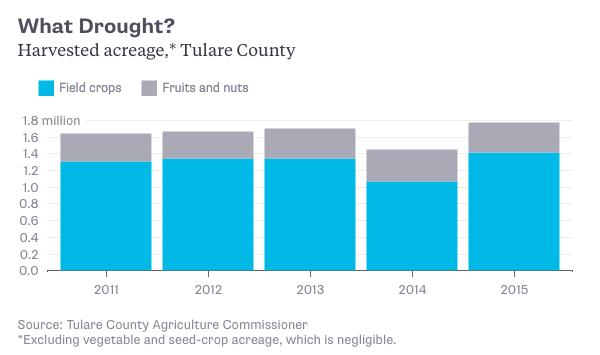

In Tulare County — the state’s and nation’s No. 1 farming county, and my place of residence for a year in the late 1980s — this groundwater pumping enabled farmers to harvest more acres of crops in bone-dry 2015 than in relatively wet 2011.

There was a big cutback in field crop acreage in 2014, which the county’s agricultural commissioner attributed to the drought, but the acreage bounced right back up in 2015. What were these fields planted with? Mainly things to feed the cows, with corn silage, small-grain silage and alfalfa at the top of the list. As already noted, milk is Tulare County’s No. 1 agricultural product. Cattle (and calves) is No. 2.

Unlike Tulare County’s No. 3 crop (oranges), milk and cattle are not agricultural products that California is uniquely suited to produce. But Tulare County’s mild winters make it a relatively inexpensive place to keep cows, and it is close to big consumer markets in Southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area. Raising beef cattle was actually the Central Valley’s first big agricultural industry. The milk cows came north later, squeezed out of the state’s former dairy heartland near Los Angeles by post-World War II suburban sprawl. Tulare County’s dairy and cattle farmers have invested a lot in being right where they are, and it’s understandable that they haven’t wanted to let a few years of drought drive them out of business. The same goes for all the rest of the state’s farmers. These are businesspeople with bills to pay, and leaving land fallow doesn’t help with that.

That said, they can’t just keep pumping and pumping. Last winter and spring were rainy enough to refill California’s reservoirs to levels last seen in 2012, but there wasn’t a lot of extra water to recharge groundwater basins, and the Sierra snowpack was still below average. Central Valley farmers often argue for the relaxation of environmental rules that keep water behind dams and in streambeds for the benefit of fish, but that’s not popular with other Californians and it’s hard to see how it would deliver enough water to make a difference anyway. Barring a series of very wet years, the state’s farming counties are going to keep getting less surface water than they want and pumping from the ground to make ends meet. Until, one of these years, the wells run dry (as they already have for some residential water users in Tulare County).

The two main paths to a more sustainable agricultural future for California seem to be groundwater regulation that puts limits on how much farmers can pump and water markets that allow farmers to profit from not using water. (Another storage reservoir or two probably wouldn’t hurt, either). The former is on its way, slowly and fitfully, after the state Legislature belatedly approved a set of groundwater-management laws in 2014. The latter exist in California, but still don’t trade much water. And so California’s farmers just keep on farming, even when there’s a drought.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Comstock’s or Bloomberg editorial board, Comstock’s Publishing or Bloomberg LP and its owners.