The future of nursing in the Capital Region might look

a

bit like Silvia Xiong.

Xiong, a 17-year-old high school senior from Marysville, sits in the lobby of the student union at Sacramento State. She’s in town with a friend for the second day of the Hmong Nurses Association conference, which is for working nurses but is welcoming youth as young as 12 on this day. She’s interested in one day working in a neonatal intensive care unit, or NICU, and seems hopeful about what she might be able to do in the nursing industry.

“For me, it’s helping people and just being able to be there during their hardest times,” Xiong says.

Her presence might also help solve a vexing problem for both Sacramento and the broader United States in recent years: a nursing shortage.

National Center for Health Workforce Analysis figures from November 2022 show there could be a shortage of over 78,000 full-time registered nurses in the U.S. by next year, and that the shortage could last several years. CalMatters reported in July 2023 that California was short around 36,000 licensed nurses, citing figures from UC San Francisco, which studies the nursing workforce.

This isn’t the first time there’s been a nursing shortage, and it probably won’t be the last, but there’s a silver lining locally. Throughout the Capital Region, various universities, health care systems and local leaders are aware of the problem and are doing something.

How the pandemic impacted nurses

The time finally came for Tanya Altmann to give up her full-time bedside nursing job in June 2023. Altmann still works part time as a nurse for Dignity Health – chairing the Sacramento State School of Nursing – “because it’s who I am,” she says. But there’s a limit to what she takes on now. “I’ll tell you the workload during COVID was hard on the nurses,” Altmann says. “And as a nurse who’s almost 60, 12-hour shifts of doing that took its toll.”

Katrina Ascencio-Holmes, interim chief nursing officer for Sutter Health, says her system experienced a nursing shortage, like other health care providers, related to the pandemic. “I’ve been in nursing for over 30 years,” Ascencio-Holmes says. “COVID was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever experienced in my career. The nurses at the bedside and the work they did was heroic.”

At Dignity Health’s Mercy General Hospital, which has 800 nurses, a staffing shortage during the pandemic could be evidenced in the hospital employing 60 traveling nurses — who move around to needed geographic areas, as opposed to RNs who can work for one hospital long-term — during the pandemic as opposed to around 33 now.

“During the COVID pandemic, we did experience definitely a larger shortage of nurses, particularly in what we call specialty areas,” says Allison Cotterill, Dignity Health Sacramento Chief Nursing Officer and Mercy General Hospital Chief Nursing Officer. “And really, we’re seeing that shortage across the nation. It’s not just isolated here in California or even in Sacramento.”

Numbers of traveling nurses also rose for UC Davis Health, which employed about 100 of them at peak versus around 20 now, according to Christine Williams, the system’s chief nursing executive. These were for specialty areas, with Williams saying, “We never really faltered from our high retention and really our low turnover and vacancy rate.”

Rachel Wyatt is chief nurse executive and interim COO for Kaiser Permanente’s South Sacramento Medical Center, which employs about 1,500 RNs. Wyatt says Kaiser’s Northern California market boasts 93 percent retention for nurses compared to 73 percent nationally, though she acknowledges the broader shortages in her industry.

“We’ve seen nursing shortages come and go over the last several decades,” Wyatt says. “The pandemic certainly made that a bit of a harsher reality, combined with nurses potentially leaving health care and then those retiring as well.”

Other reasons for the nursing shortage

Not everyone calls what’s going on a nursing shortage, such as the California Nurses Association, which contends it’s more a shortage of good-paying nursing jobs. Cathy Kennedy, the association’s president and an RN in the NICU at Kaiser Roseville, acknowledges that while there are more than 500,000 active nursing licenses in California, only around 325,000 of these nurses are working.

And then there’s the hazards of the job. “I’ve been doing this for a long time, and a lot of it is about safety protections,” Kennedy says. “COVID taught us a lot of employers are not ready.”

Sometimes, it’s not just a pandemic that takes nurses away from the bedside. Deb Bakerjian has an active nursing license but hasn’t worked clinically since about 2015, she says. Instead, she is a clinical professor and associate dean for practice at UC Davis’ Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing and was one of the first faculty members hired, back in 2009. Working together, they had to build the program, which was a major undertaking and “at the time, we did not have mechanisms set up so that our faculty could practice even in the health system,” Bakerjian says.

And nursing shortage notwithstanding, the glide path to a job is not always a smooth one.

Nou Thao, president of the Sacramento chapter of Hmong Nurses Association, graduated in 2020 with a bachelor of science in nursing, or BSN degree, from Sacramento State. She faced a tough job search in Sacramento and considered working in Fresno before landing a position as a nurse for the Sacramento Community Clinic.

“I think I really like the advocacy part, just being able to help them beyond the hospital and helping them maintain their health in long-term,” Thao says.

What’s being done about the nursing shortage

Different efforts address the nursing shortage. At Sutter Health, the system has decreased its turnover rate for nurses by 9 percent since June 2023. It has focused on strengthening its relationships with nursing schools and using its residency program to help train new nurses. The system boasts 16,000 nurses. “That doesn’t happen easily,” Holmes says. “It’s a concerted effort together to making it happen.”

Kaiser Permanente Northern California has hired around 9,000 nurses over the past few years, with Wyatt saying the system continues to refine recruitment strategies. “We have not left our foot off the pedal anytime in the last several years, making sure that our workforce remains stable,” Wyatt says.

Allison Cotterill, Dignity Health Sacramento and Mercy General

Hospital chief nursing officer, says the nursing shortage is

across the U.S. and not just Sacramento.

UC Davis Health has used new graduate programs and what Williams termed “creative training programs” to help staff transition to new areas of nursing.

Cotterill says Mercy General is in its fourth cohort of a nursing

residency program that is helping train 20 new nurses annually.

She also says a shadow program for high schoolers has allowed

them to “help the nursing staff in the different departments

either provide indirect patient care or support services within

the unit themselves.”

Multiple legislative bills address the nursing shortage. AB 2104,

by California Assemblywoman Esmeralda Soria (D-Fresno) would

create a pilot program allowing up to 10 community colleges to

offer BSN programs. “It is going to provide us a bit of a tool,

another opportunity to kind of expand the workforce in nursing,

at least for in the short run,” Soria says. “Because we know that

by 2030 the shortage is going to be really significant,

especially for our region.”

California Sen. Dave Cortese (D-San Jose) is sponsoring SB 1015, which would address what the California Board of Registered Nursing can and cannot do in regard to clinical placements. “That clinical placement issue is a bottleneck in exacerbating the nursing shortage,” Cortese says.

Then there’s everything the Sacramento area does to train new nurses, with a growing number of schools. “We produce a lot of students and a lot of new grads,” says Julie Holt, director of Sacramento City College’s nursing program. “We have 12 schools in this region alone.”

This number has been growing. University of the Pacific just graduated the first class from its nursing program, which opened in 2022 and is located on the McGeorge School of Law campus in Sacramento, according to Ann Stoltz, the nursing program’s chair. She called the nursing shortage “the big impetus” for launching the program, though where graduates can work also matters.

“We’re not just feeding the Sacramento area, but we’re feeding the Stockton area as well, which is a higher-needs area,” Stoltz says.

In Rocklin, Jessup University welcomed the first cohort of students for its BSN program in the spring of 2023 and has 69 students enrolled as of this writing, according to Jen Millar, associate dean for the university’s School of Natural and Plant Sciences and director of the BSN program. The university’s focus as a Christian school could help differentiate its nursing program, with Millar saying, “Our nurses will be equipped to be a registered nurse, obviously, but they also may be interested in doing overseas missions or local missions.”

In early August, California Northstate University – a multi-discipline medical school in Elk Grove – announced the launch of its new BSN program at its Rancho Cordova campus, with the school’s College of Health Sciences Dean Dr. Heather Brown saying in a statement, “CNU is committed to educating and nurturing future nurses who will make a meaningful difference in the lives of patients and the communities that they serve.”

Sacramento State’s nursing school admits 160 students each year and graduates 145-150 annually, according to Altmann, who’s worked at the school since 2002. “In my time at Sac State, we’ve actually grown our enrollment, which is really tough right now to do,” Altmann says.

Bakerjian says UC Davis’ nursing school received a $6 million grant from the U.S. Department of Labor and an additional $1.2 million from her school’s dean to bolster faculty recruitment. The program has also been working to increase the diversity of the RN workforce.

Community colleges also train nurses. Lisa Lucchesi is dean of the health and fitness track at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, which oversees the school’s nursing program and students. The program increased from 80 enrolled students in 2022 to 150 this semester thanks to a $3.8 million federal funding boost. “We probably do pride ourselves on them being … prepared clinically for the bedside care that they deliver,” Lucchesi says.

Sacramento City College has had an RN program since 1909 and a vocational nursing program in recent decades. Holt is proud of faculty retention, how students are prepared and the impact on their lives. “It absolutely changes the student’s life when they go through this program,” Holt says.

The program’s students include Pan Lee, 34, who formerly worked in the export business. Asked what motivated her to go to nursing school, she admits she’d be lying if it wasn’t partly for financial reasons. Job security helps, too. “There’s always a need, a demand for this position,” Lee says.

For those who pursue nursing, it can be a lucrative career choice. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports the average annual nursing salary is $133,000 as of May 2022. It is also, for many, a calling. Lucchesi remains an active nurse, balancing her duties at Delta College with working a day or two per month at San Joaquin General Hospital. She worked through the pandemic.

“People were sick and dying at the time,” Lucchesi says. “They needed help.”

Recommended For You

Are We Ready for the Electric Revolution?

The Capital Region is leading the charge to make California EV compliant in the next decade

These days, there is a sense of possibility in Sacramento when it comes to zero emissions technology. Sacramento may not have the population numbers of New York or Los Angeles, but when it comes to EV infrastructure the California capital plays second fiddle to no city in America.

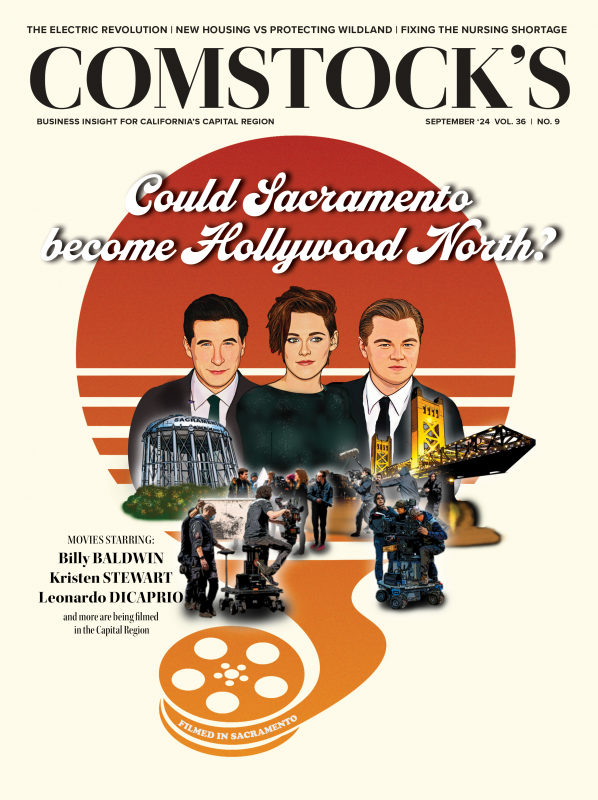

Ready, Set, Action!

Filmmakers big and small are finding the region a congenial place to make movies

For several days this winter, Sacramentans got to play “Spot the Movie Star” while Leonardo DiCaprio and William Baldwin were both in town filming two different movies at locations all over the city. It begs the question: Could Sacramento become Hollywood North? The city and nearby Placer and El Dorado counties have a growing film industry that brings millions of dollars and thousands of jobs into the region.

We Oughta Be in Pictures!!

FROM THE PUBLISHER: Our region has long been one of Hollywood’s well-known secrets. Because of the area’s natural beauty and close to year-round clement weather (the two compelling reasons that made filmmakers leave New York in the early 1920s for a stronghold in Southern California), movies, TV shows and commercials have been shot here for years. What if we had our own film studio?

From Farm to Glass

They’re just miles apart, but Capital Region wine regions are distinctively different based on their climate, terrain and soil

Each of our four wine regions has its own unique terroir, a French term describing the soil, climate and sunshine that give wines their distinct character. These winemakers want consumers to consider their wines farm-to-fork — that is, farm-to-glass.

What Does a California Lobbyist Do?

Often referred to as the third house of the state legislature, lobbyists spend long days advocating for their clients

California is one of only 10 states that has a full-time professional legislature, and last year, companies and industries spent a record high $480 million on lobbying efforts in the state.

When the Sun Sets on the Golden Years

The hardship and high cost of caring for a loved one in decline

For eight weeks in the summer of 2023, Laurie Watkins took leave from work to be her mother’s live-in caregiver. She had joined what is often referred to as the sandwich generation — those who are caring for both their children and their aging parents.