In a huge hangar in an industrial park off of Highway 50, its silver insulated roof propped up by yellow-painted girders, Aashish Dalal of the California Mobility Center teaches young auto mechanics the ins and outs of working on electric vehicles. Dalal’s “Intro to Green Careers” classes routinely bring in 20 to 30 students per session, many of them sent CMC’s way by the state’s Sustainability, Equitability, Education and Diversity program, or SEED.

Dalal is, by nature, a tinkerer. A striking man, with a shaved head and long gray beard, his eyes sparkling with curiosity behind large black-framed glasses. He has long been fascinated by the possibilities of zero emission vehicles. Hanging under the roof of the hangar is the top half of a classic lowrider, a ruby red 1964 Chevy Impala. Dalal is working with students from the Sacramento Arts and Vocational Academy High School to substitute out the Chevy’s gas motor for a 300-horsepower electric motor. The bottom half of the car — including the frame and wheels — he keeps at his shop in Dixon.

The California Mobility Center receives a state workforce grant and some dollars from the Air Quality Management District, which operates in partnership with SMUD and with Sacramento State. It’s part of a full-court effort to push the Capital Region to the fore in promoting zero emission vehicles and the broader regional infrastructure needed to support a radical reimagining of both the public vehicle fleet and the far larger stock of vehicles in private hands. Designated a “clean city,” Sacramento has received an influx of federal and state funds to boost its EV infrastructure, as well as money from the federal settlement with Volkswagen that came after the German car company was caught fudging data on the pollution linked to its diesel vehicles.

The greater Sacramento region is, says Madeline Brown, lead project manager for the clean transportation division of CALSTART’s San Joaquin Valley Regional Office, “really demonstrating successes and continuing to lead the way at the engagement level.” With cutting-edge research being conducted by nearby UC Davis’ Institute of Transportation Studies, the California Mobility Center, Sacramento State and other hubs for environmental science, this “is a region where different factors have combined to enable it to be successful — and people are taking advantage of the opportunity.”

When the move to electric began

The city of Sacramento’s effort to wean itself off of fossil fuel-based modes of transportation kicked off in the 1990s, years before most urban areas in the U.S. pivoted to the issue, when SMUD first took the lead installing EV chargers in the region. Since then, that effort has spread beyond the city boundaries to encompass the entire region, and, with Governor Newsom’s positioning of California at the forefront of international efforts to limit climate change, to the state as a whole.

A generation after SMUD’s first baby steps toward greening the local economy, the Sacramento region remains at the cutting edge of this process. The well-funded, well-lubricated effort ranges from subsidies for consumers purchasing EVs and for establishing charging stations. The Sacramento Electric Vehicle Association estimates there are 150 charging plazas and 987 fast chargers in the nine-county region, with many more coming online in the next few years — through to investments in new technologies such as bidirectional charging systems that allow the large battery packs of electric buses, trucks and SUVs to be used to replenish the power grid or to keep home air conditioning systems and lights running during power blackouts.

SMUD is already using electric trucks in its fleet. Rachel Huang,

customer and grid strategy director, says SMUD provides subsidies

to customers seeking to install at-home EV chargers.

It includes city and state agencies, local nonprofits, large private companies and a growing alliance of consumers desirous of using their purchasing power to push the region toward cleaner energy choices. (The Sacramento Electric Vehicle Association sends its newsletter out to roughly 700 people each month, and its volunteers hold events around the city to educate residents on the economics of electric vehicle ownership.) The effort even includes using dead trees and walnut shells in rural areas to generate hydrogen that can be used by owners of fuel cell vehicles at hydrogen fueling stations in the region.

If the strategy succeeds, and if the kinks can be ironed out of the system when it comes to building enough EV charging stations and keeping the chargers functioning at a high level of reliability, by 2030 the Capital Region will have 300,000 EVs on the roads, 27,000 of which will be medium- and heavy-duty trucks. In addition, it will also have thousands of hydrogen cell vehicles. By that year, if the targets are met, half of all commercial vehicles in California will be zero emission vehicles; by 2040 the state hopes to have moved the entire commercial fleet, comprised of both state-owned and privately-owned vehicles, away from fossil fuels.

In the Sacramento region alone, these vehicles will rely on hundreds of millions of dollars in investments being injected into the system over the coming years to subsidize the purchase of these vehicles and to build up the region’s charging infrastructure. The California Air Resources Board has, under a program cumbersomely known as the Hybrid Zero Emission Truck and Voucher Incentive Project, or HVIP, distributed hundreds of vouchers totaling over $30 million to truck fleet owners in Sacramento County. Another program, for off-road vehicles such as forklifts and tractors, has handed out $9 million in the county. And the California Energy Commission has pumped several million dollars more into grants used to build up the local charging infrastructure.

“We’re seeing a lot of momentum now relating to transport electrification,” says Rachel Huang, SMUD’s customer and grid strategy director. SMUD provides subsidies to customers seeking to install at-home EV chargers, and using California Energy Commission grant money (earlier this year, the CEC approved a nearly $2 billion plan to expand zero emissions vehicle infrastructure), the agency has been working on a charging network that will allow for huge numbers of vehicles to be charged without overloading the grid.

Partly this strategy involves using bidirectional charging vehicles, such as school buses — which are idle for large parts of the day. The Ford F150 lightning truck and the Tesla cybertruck can also add energy stored in their batteries back into the system. Partly, it involves providing customers financial incentives to charge their cars overnight when there are less demands on the power supply than there are during peak usage times, a system SMUD has labeled “managed charging.”

In the surrounding region, outside of SMUD’s coverage zone, the nonprofit organization Valley Clean Energy is working with PG&E in communities throughout Yolo County to generate green energy that can be added into the grid and to encourage adoption of zero emission vehicles. As a part of the effort to green the region’s energy usage, the Sacramento Area Council of Governments gave VCE nearly $3 million to install public EV chargers. VCE has also distributed large sums to help low-income customers purchase electric vehicles, with some families qualifying for up to $4,000 in subsidies. And it is currently working on a plan to provide incentives to households needing electric panel upgrades in order to run EV chargers.

“Our role is both beefing up our zero emission fueling infrastructure — being able to put chargers out in the region — but also hydrogen fuel in the region. We are not in this alone; we’ve created a strong alliance with SMUD, the Sacramento Area Council of Governments and Sacramento Rapid Transit,” explains Jaime Lemus, director of the transportation and climate change division of the Metropolitan Air Quality Management District.

In poor communities, the alliance aims to put in free charging stations and community-use electric vehicles, provided via a partnership with Zipcars that can be used for free by local residents upon showing their driver’s licenses. It has also established a Clean Cars for All program, allowing local residents to trade in their old cars and apply for a voucher toward the purchase of EVs or plug-in hybrids. During the first phase of this program, the vouchers were pegged at $7,500. Recently, however, the alliance agreed to increase the value of the voucher to $9,000.

In the next decade, Lemus says, MAQMD hopes to create upwards of 50 “mobility hubs” around the city, places with large numbers of fast chargers that consumers can use to refuel almost as quickly as they would do at a regular gas station. A company called WattEV is also investing $62 million in building a charging depot for trucks on a 118-acre parcel of land alongside I-5, just south of Sacramento, to be completed by the end of next year.

Sacramento is in the forefront of the move to zero emissions

These days, there is a sense of possibility in Sacramento when it comes to zero emissions technology. Sacramento may not have the population numbers of New York or Los Angeles, but when it comes to EV infrastructure the California capital plays second fiddle to no city in America.

Ollie Danner is the CEO of ZeroRig.com, a company that, via the Internet, links up fleet operators looking to green their fleets with dealers who are selling or leasing electric trucks. In recent months, he explains, the company has been on a PR blitz, holding large events at dozens of venues around the region. Later this autumn, it will bring up to 1,000 people to a gathering at the CMC’s large hangar space. At these events, consumers can test drive dozens of different makes of ZEVs and listen to speakers talk about the capabilities of these new technologies, and fleet operators can meet with representatives of the California Air Resources Board.

“We’re basically bringing the big event to the local area,” Danner says.

“It’s a rolling information tour.” At the Port of Stockton recently, the organization hosted what it termed the world’s biggest zero emissions convoy. Later this year, it will repeat the show in Sacramento.

Around the region, cutting edge technologies are now being developed and deployed. The California Mobility Center is, for example, working on creating a fleet of 20-foot-long shipping containers that will come complete with 300 kilowatt hours worth of battery storage, which can then be fed back into the grid during times of overload. In 10 to 15 years, says Orville Thomas, CEO of CMC, “you are going to see more microgrids that are community-based and neighborhood-based, that are a combination of solar and batteries that allow for nimble allocation of energy.” Most new homes, he says, will come with their own batteries to store energy so that “you can flip a switch and go off grid at times when SMUD needs electricity for other purposes.”

Because these changes are being implemented in real time and without a huge amount of accompanying hoopla, and because the funding is often distributed via organizations and departments with cumbersome acronyms standing for hard-to-remember titles, it’s easy to forget just how transformational they could be. Over time, however, zero emissions research and investments will dramatically change how Sacramentans go about their daily lives.

In the coming years, there will be, says CALSTART’s Brown, a huge expansion in microgrids, designed to withstand the growing challenges to the power supply by extreme weather and of wildfires.

There will be “vehicle to everything” charging systems, whereby an increasing number of cars and trucks can be used to power homes. And there will be massively enhanced battery recycling systems in place to deal with all the waste products that come with electric vehicles. There will also be a growing recognition of the need to provide meaningful assistance to residents of low-income communities to help transition all residents away from oil-based transport and toward a zero emissions future.

Taken as a whole, energy and transportation experts look at the region and see the possibility of radical transformation. Here in Sacramento, Brown says, “there are places and there is space to try new things.”

Recommended For You

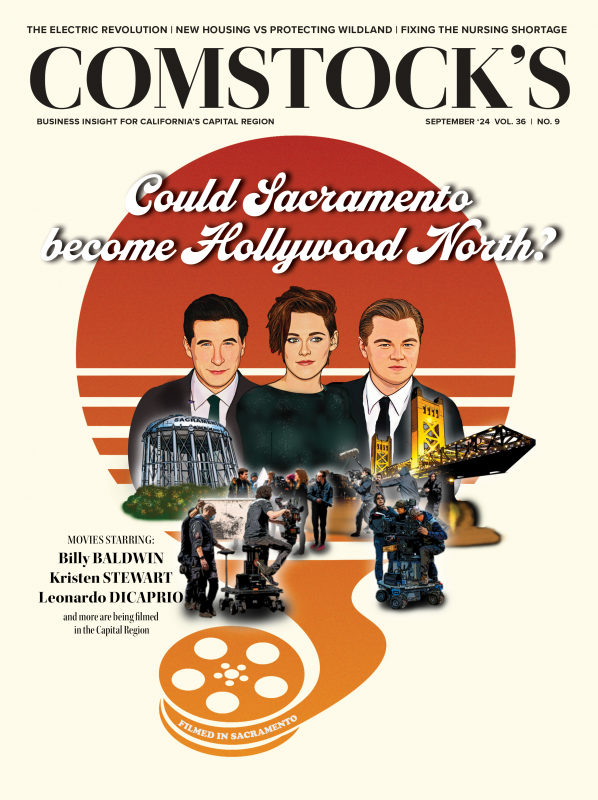

Ready, Set, Action!

Filmmakers big and small are finding the region a congenial place to make movies

For several days this winter, Sacramentans got to play “Spot the Movie Star” while Leonardo DiCaprio and William Baldwin were both in town filming two different movies at locations all over the city. It begs the question: Could Sacramento become Hollywood North? The city and nearby Placer and El Dorado counties have a growing film industry that brings millions of dollars and thousands of jobs into the region.

We Oughta Be in Pictures!!

FROM THE PUBLISHER: Our region has long been one of Hollywood’s well-known secrets. Because of the area’s natural beauty and close to year-round clement weather (the two compelling reasons that made filmmakers leave New York in the early 1920s for a stronghold in Southern California), movies, TV shows and commercials have been shot here for years. What if we had our own film studio?

From Farm to Glass

They’re just miles apart, but Capital Region wine regions are distinctively different based on their climate, terrain and soil

Each of our four wine regions has its own unique terroir, a French term describing the soil, climate and sunshine that give wines their distinct character. These winemakers want consumers to consider their wines farm-to-fork — that is, farm-to-glass.

What Does a California Lobbyist Do?

Often referred to as the third house of the state legislature, lobbyists spend long days advocating for their clients

California is one of only 10 states that has a full-time professional legislature, and last year, companies and industries spent a record high $480 million on lobbying efforts in the state.

When the Sun Sets on the Golden Years

The hardship and high cost of caring for a loved one in decline

For eight weeks in the summer of 2023, Laurie Watkins took leave from work to be her mother’s live-in caregiver. She had joined what is often referred to as the sandwich generation — those who are caring for both their children and their aging parents.

Sleepy Suburbs? No Way

These Capital Region cities are buzzing with energy and ambition

A generation ago, Sacramento was the undisputed king of commerce and culture in our region. But the once-quiet suburbs are growing up fast. In fact, thanks to years of quiet community building, the edge cities are leading the way in defining the modern Capital Region.