It’s the first day back at work for a female employee after a pregnancy. She’s talking with a male manager who tells her he’s surprised she’s back so soon — his wife didn’t work for years after their first child.

In leadership meetings, a female manager is usually interrupted by male colleagues when she talks. The male managers get respectful attention, and the CEO sometimes compliments them for offering ideas that were ignored when she suggested them.

An African-American employee is told that he “doesn’t sound black,” a Jewish employee hears that she “doesn’t look Jewish” and a gay staffer’s supervisor tells him he “doesn’t act gay.”

Those are real-life stories, according to several experts on workplace discrimination. They’re also examples of subtle comments and behavior that have lately come to be known as “microaggressions.”

Allegations of overt on-the-job sexual harassment have been front and center in Sacramento after three cases last year in which city employees filed claims against supervisors for allegedly soliciting them for sex. But those who work on harassment prevention say that under-the-radar microaggressions need equal attention. Not only can they put companies at legal risk, but they also can cut into productivity and in the long run cost them money.

The High Cost of Bias

Prejudice comes in all flavors — targeting gender, race, ethnicity, religion, age, sexual orientation and more. And if its more overt forms — say, a supervisor’s solicitation of sex — are like a frontal assault, microaggressions are something like a sly shove. Often they’re unintentional, and they may not even reference anything sexual. And they can go in all directions — men targeting women, women targeting men, people of the same gender targeting each other, supervisors targeting staff and staff targeting supervisors.

“If the boss says, ‘Hey I don’t want women working for me,’ that’s overtly aggressive,” says Vida Thomas, an attorney who heads Weintraub Tobin’s workplace investigations unit. What makes microaggressions so challenging for alleged targets is they’re merely suggestive. “So [the target] is always asking, ‘Am I being hypersensitive? Am I overreacting? Am I reading too much into this?’” Thomas says.

Derald Wing Sue, a California-licensed psychologist who teaches at Columbia University and writes widely on cultural competence, gives a common example. A female doctor wearing a stethoscope is approached by an intern who asks, “Where’s the doctor?” and is surprised by the answer. The subtext of the intern’s assumption is that women aren’t capable in leadership roles, Sue says. In fact, that example is no anomaly — in a 2014 study of 60 female scientists of color by the Center for WorkLife Law in San Francisco, survey respondents reported routinely being mistaken for janitors.

The impact on performance may be anything but subtle. Sue points to studies showing that the mere suggestion of bias can make it harder for these employees to focus. In a classic 1999 experiment that’s been validated several times, a group of male and female college students were tested at math, and before starting were told that the test results usually showed gender differences. The men significantly outperformed the women. But when a matched group was told that the test results usually found no gender differences, men and women performed equally well.

Microaggressions can be hard on a company’s profitability in other ways, most obviously by putting it at legal risk. Courts have defined sexual harassment as incidents that are severe or so pervasive that they create a hostile work environment. The “pervasive” part of that equation could comprise minor incidents, including microaggressions. Taken together, those may be judged by a reasonable person as creating a hostile work culture, says Sue Ann Van Dermyden of Van Dermyden Maddux, a Sacramento law firm that investigates alleged workplace discrimination. (On April 1, new rules for employers went into effect in California: Employers with five or more staff now must have written policies against harassment, discrimination and retaliation that contain specific information, such as the complaint process.)

“If you have a climate in which you’re losing talented individuals because they feel like they’re pushed out or it’s a culture where they can’t succeed because the climate is hostile, that’s really a big waste. You’re not accessing the full range of the talent pool that should be available to you.” Jamie Dolkas, director of Women’s Leadership, Center for WorkLife Law

There’s also the cost of employee churn. “It’s really expensive to recruit, hire, and train employees,” says the Center for WorkLife Law’s Jamie Dolkas. “If you have a climate in which you’re losing talented individuals because they feel like they’re pushed out or it’s a culture where they can’t succeed because the climate is hostile, that’s really a big waste. You’re not accessing the full range of the talent pool that should be available to you,” she says.

Retooling the Work Culture

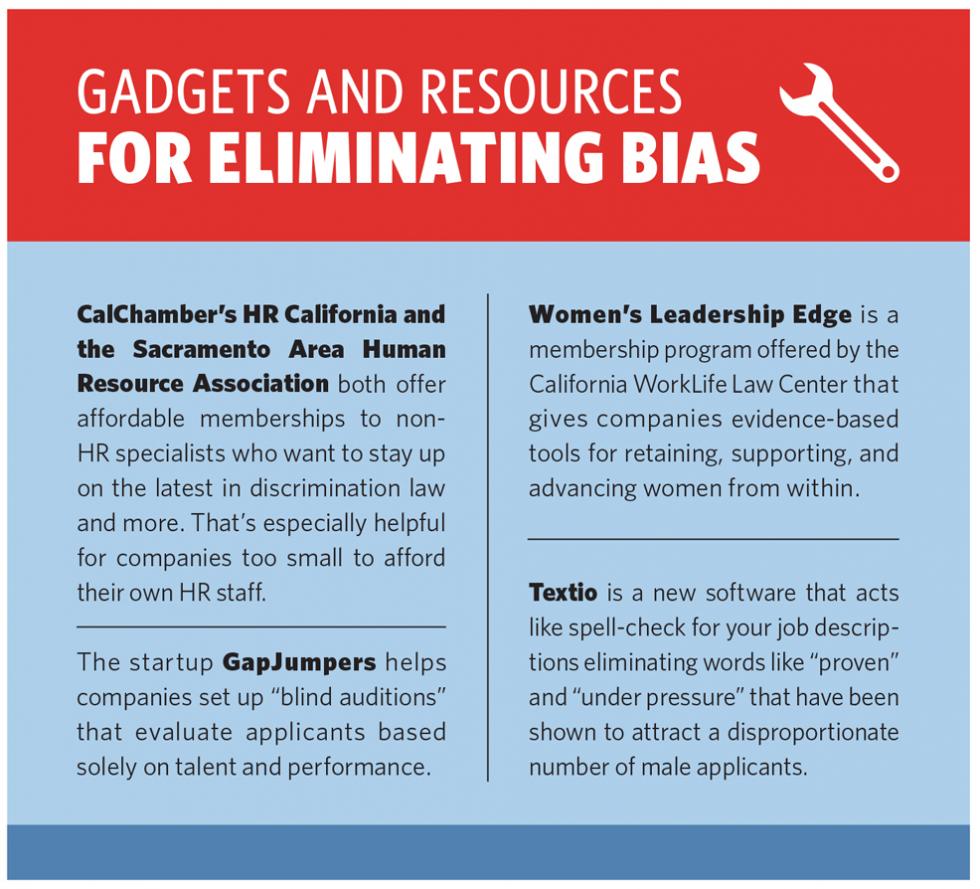

Dolkas says we need to go beyond talking about whether there’s a problem of workplace bias and actually help companies put in systems that can fix it. To that end, the Center for WorkLife Law has developed a set of “bias interrupters” — systems that let companies identify and measure bias and then re-engineer their practices.

That approach has four parts. First, companies conduct an evidence-based assessment to identify problems — say, pay disparities between men and women doing the same work. That usually means getting employee feedback through a survey, a focus group or confidential interviews.

Second, companies develop objective metrics to measure the size of the problem and set goals. In the case of pay disparities, for example, personnel records can establish the current baseline. Metrics also help leaders sort out where the problem occurs: Do the disparities crop up during the hiring process or when raises are negotiated?

Third, leaders put a bias interrupter into place. Again using pay disparities, companies that include the phrase “salary negotiable” in job ads virtually eliminate pay disparities because women then feel free to bargain at hiring time.

Finally, the firm reassesses its metrics after a period and makes more changes if necessary. Workplace experts also say a company’s state-mandated harassment prevention training should deal head-on with microaggression. Well-planned trainings can help people realize that subtle expressions of bias usually happen because of an employee’s worldview rather than malice. “Every single person has bias,” Van Dermyden says. “You can punish people all day long but not change their attitudes. It’s far better to offer training that helps people see things from another person’s perspective.” Training should target managers rather than staff, although staff can be briefed on the overall policy and the complaint process, says Jennifer Duggan of Duggan Law Corporation, which represents businesses in legal disputes.

Thomas, of Weintraub Tobin, says good training helps people recognize that we all see the world through filters. “For me, the essence of harassment prevention training is getting folks to understand that we’re coming into the workplace with unique backgrounds consisting of so many factors. There’s geography: Where were you raised? Were you raised by one parent or two? Was your home religious or not, and if so what religion? Did you grow up in a suburb or inner city? Have you traveled or lived outside the country? On top of that you add gender, ethnicity, ancestry, race — all of these factors unique to these people. And then we put them in one constrained space and we expect that they’re not going to bump up against each other? Of course they are. That’s the challenge.”

Yet it’s also possible to make the definition of microaggression so elastic that it ceases to hold anything. Employees and students in some cases have been told that saying “bless you” or wearing green and red in advance of the holidays is a microaggression, says Jonathan Segal, an employment attorney and national authority on employment issues at the Philadelphia-based Duane Morris Institute. He says cases like those trivialize the serious and persistent instances of real harassment that do injure victims and organizations. And if employees feel that anything could be a microaggression and they’re walking on eggshells, they’ll just avoid interacting with people who are different, which itself could be discriminatory, he says.

Training Yes, Company Policy — Maybe

There’s no consensus about whether firms should tackle microaggression in their corporate policies. Dolkas favors it — by addressing subtle forms of bias in their policies, companies can better protect themselves from lawsuits, she says. That’s because if behaviors are taking place that create a hostile work environment, they could rise to the level of sex discrimination. In that case, it’s better to have a wider definition of discrimination so that those problems get reported and can be stopped early, she says.

But Van Dermyden says she’s not sure companies can realistically create anti-harassment policies that address everything that could arise. “I don’t even know how you’d create a policy to cover all of the different types of comments that could comprise microaggression,” she says. Many comments and behaviors that could be perceived as microaggression arguably already fall within a company’s anti-harassment policies, she adds.

If they do tackle microaggression in their policies, Segal says they need to use careful language; they should label examples of subtle bias as “inappropriate” or “unacceptable” instead of “unlawful.” Among the risks of using a term like “unlawful”: different jurisdictions have thresholds for what constitutes harassment, so if an employee is fired for “unlawful” behavior that turns out not to be, the employee could sue for defamation.

But another emerging area of gender equality may well merit changes in policy — the treatment of transgender employees. In February, the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing issued new guidance that requires employers to allow transgender workers to use restroom facilities consistent with their gender identity. Companies aren’t required to have a policy covering transgender issues, says attorney Samson Elsbernd, of Wilke Fleury. Still, he advises firms to be proactive, as they may not know when they have an employee who identifies as transgender. A policy provides expectations for how other employees treat transgender coworkers and signals that the company has taken all reasonable steps to prevent harassment should a lawsuit arise.

Thomas is happy that the subtler forms of bias now have an official name. She credits the younger generation — particularly on college campuses — for raising awareness. “I don’t blame young people for saying, ‘No, we want to take this conversation to the next level,’” she says. “What’s happening is that people are being harmed and the people doing the harming are often completely clueless that they’re doing so.”