Whether it’s layers of tiny microchips or rows of dead batteries, each work in Muzi Li Rowe’s Magical Thinking series is like peering into a tiny museum where the most microscopic parts of now-defunct personal technology devices, from old Nokia flip phones to disposable cameras, become individual hallmarks of consumer culture. The small sculptures are visually appealing, with layers of elements suspended in crystal clear resin, formed into perfect rectangular bricks or pyramid shapes, sometimes infused with glitter or even fairy lights.

For Rowe, a Sacramento State and American River College photography instructor who is a collector of “techno scraps,” these artworks made of dissected e-waste are both “personal” and “have this very cold machine-like appearance.”

Rowe builds analog cameras, like this plywood medium format film

camera with three interchangeable lens boards using rows of tiny

cell phone camera lenses. (Photo courtesy of Muzi Li Rowe)

Rowe also thinks about the relationship between time, technology and consumption. “Just the way that we see a phone, and that just gives off a timestamp. … If we look at an early mobile phone, it looks so ancient. They’re actually not that old. But just the way that technology has been developing so exponentially,” she says, adding that newer technology becomes outdated more quickly. “So in that sense, I also think a lot about consumption and waste.”

Rowe’s work bridges the gap between modern and traditional culture, often combining both digital photography and analog darkroom processes. Her series of hand-built cameras and projectors use modern materials like electric cords and motors while also incorporating vintage camera lenses or the use of film. Trained in both digital and traditional analog photography, Rowe uses both mediums and often mixes the two in addition to making sculptures and installations.

“Whatever works, really,” says Rowe, who describes herself as a mixed media artist and a photographer. “When it comes to my art practice, I don’t really restrict myself to just a photographic medium.”

Rowe does, however, create photographs of technology and culture — like her black and white series of fast food chain restaurants, called “Big Boxes,” and her “Vanitas” series of color still lives of various disembodied photographic parts — using film, which she develops in her home darkroom, converted from a guest bathroom. It’s also where she pours her resin.

A more recent project, funded by the Sacramento City Office of Arts and Culture’s Seeding Creativity grant, involved the creation of Chinese knots using old cables of all kinds, including headphone wires, cell phone charging cords, power cords, telephone, ethernet, audio-visual and coaxial cables.

Rowe, who was born in Beijing, China, and lived in Sydney, Australia, during high school and college before moving to the United States, decided to learn the traditional craft of making Chinese knots as a way to reconnect with Chinese culture.

Rowe’s project Good of Nothing incorporated e-waste into the

making of Chinese knots, which Rowe says is a way to connect with

her culture. (Photo courtesy of Muzi Li Rowe)

“I developed this coping mechanism against prejudice just by distancing myself from my own culture,” she says. “That’s kind of something that I’ve been doing subconsciously. And I’m just like, you know what? I’m going to embrace my culture. I’m going to learn this traditional craft and just see what happens.”

The project differs from some of Rowe’s previous work in that it is much more personal to her. It has also afforded the opportunity to share the craft with others, through public workshops held at Axis Gallery, Verge Center for the Arts and Crocker Art Museum, which has had positive engagement.

“People are fascinated, and it’s so interesting. … Humans like to make knots,” Rowe said. “It’s like a universal language, right?”

An exhibition of the project, called 無知爲用 (Good of Nothing), was displayed at Axis Gallery in June of 2023.

Your work fuses vintage, analog and modern technology. Is that intentional?

I am very interested in the idea of technology, even though I’m not a very technical person, but just the idea of the technological development since the Industrial Revolution and how that is affecting the way that we perceive the world in general, and also how artists create their work.

I think about technology all the time, and I try to find ways to use that as my subject.

Your work seems very process-based. Is the process as important to you as the end result?

Yeah. It’s just like, you have a plan and then how you get there, it’s never how you planned it. Usually my mistakes and whatever happens along the way, that informs me on where to go next. I think it’s great that some people, they have a plan and they’re very strategic and they complete their project. I don’t have that ability. …

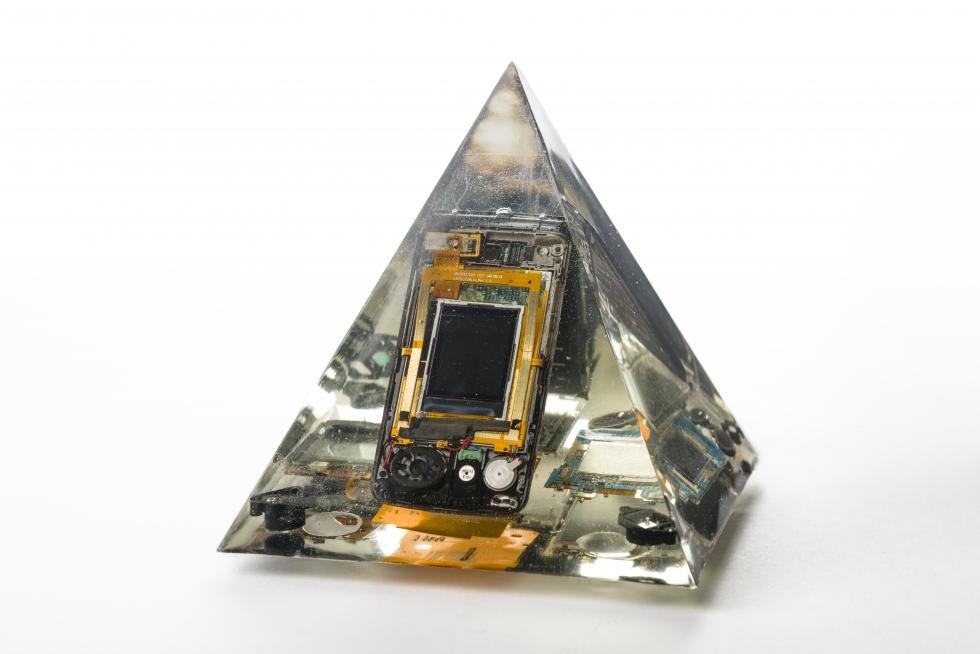

In this sculpture, titled Pentahedral Faraday Cage No. 1, a

pyramid formed of epoxy resin encases an outdated dissected cell

phone. (Photo courtesy of Muzi Li Rowe)

I think the idea is always more important (than) techniques. And when I was making cameras — you want to calculate, you want to be precise, you want the focus to be sharp, right? I feel like that’s the first thing that we all think about. But during the process, I just kind of embraced the fact that, A, I’m not very good at it. B, that’s not really the point. I think really it is about all these phones that I’ve collected on eBay and I took them apart, and just this whole clumsy process is what’s meaningful to me.

How did you get into making this work? Was there something that inspired you to do that, or was it more just that you just liked experimenting with parts and things?

I think this got started when I took apart a phone, and then took the little camera out, and then I put a piece of tracing paper behind it, and I saw the projection of the light bulb. I was like, damn, that’s so cool. It’s just like how pinhole (photography) is just forever magical. It’s just like you have a lens and you have a light source, and you just see that projection. I’m like, I’m making a photo from this. You know what I mean?

And then I kind of got obsessive with just collecting phones. So I did this at the same time too, I was also photographing it. So I think it’s like a Nokia flip phone or something (photographed) on wet plate (collodion). … There’s always something humorous.

It’s just like all this technology that’s gone obsolete. There’s so much to it. The semiotics of it, the personal connection to it.

You said you view the tech waste sculptures as “personal.” Can you explain that?

Yeah, it’s really fascinating. It’s just how I think. There are just so many layers to these objects. On one hand, it’s personal because a lot of people, they see an old Nokia or something and they’re like, “Oh, I used to have that.” You know, there’s something very personal about these devices.

Where do you source your e-waste materials?

Everywhere. Primarily eBay. I love thrifting. I mean, I’m really lucky in a way because I collect a lot of e-waste, and everybody always gets rid of their e-waste. So for a while, I mean, I haven’t really purchased anything. The people just give me their old crap, and I say yes to everything, and sometimes I’m just like, “Oh, this thing, I don’t know, but I’ll keep it and maybe one day, one day I’ll find a use for it.”

How did you end up in Sacramento after living in China and Australia?

After I graduated college, I went back home. I worked for a few years at galleries. I worked for a few years, and I met my husband in Beijing. He was in the Army. He was visiting Beijing. We met and we had this long distance relationship. He was stationed in Hawaii at the time, but he’s originally from Monterey, California. So after we got married, I lived in Hawaii for a couple of years, and then we both applied for schools in California. He was also pursuing his graduate degree. So yeah, I got into UC Davis. So we ended up in Davis and then moved to Sacramento.

Rowe uses both digital and analog photography to create art that

merges the modern and traditional. Here, she uses the historic

process of wet plate collodion to photograph a circa-2003 Nokia

6800 with a flip-out keyboard. (Photo courtesy of Muzi Li Rowe)

When you were at UC Davis, did you have an emphasis there?

Yeah, so UC Davis, their MFA program is pretty interdisciplinary. So you can do whatever you want, and they encourage you to try all the things. That’s when I started learning how to work with wood, and I wanted to make three dimensional objects. Before that, it was very flat, just two dimensional.

Do you consider the digital photography that you do as art? Or is it more of a commercial thing to you?

Well, I mean, for my photography freelance thing, everything’s digital. But for my art, I do both. Whatever works really. … I built this stereo camera before and I wanted to build the camera and have that as an analog camera, but that just didn’t work out. I wanted to make an 8×10(-inch format) stereo camera … and it didn’t work out, so I used my digital camera to photograph the projection on the stereo camera.

Can you tell me about your photography business, 18% Labs?

Yeah. Mostly it’s just documenting exhibitions, cataloging artwork. I’ve done some printing as well, so I’ve done some commissions here and there, but mostly artwork documentation.

An iPhone 5c is encased in an epoxy resin brick, its components

suspended in transparent layers. (Photo courtesy of Muzi Li Rowe)

I saw on your Instagram that you’re also the owner of Tekhne Handmade. What is that?

So that’s just kind of a little jewelry thing that I started. I’ve been making all these earrings. It’s because while I was pouring epoxy resin, there’s always a little bit on the bottom of the cup, and I just pour some (to use up the extra resin).

What are you working on now?

I have a show in Axis in March. I wouldn’t say that I’m making new work for the show. I’ve been doing a lot of drawings on the side. It’s just something that I’ve been doing for several years, and I just want to show all of my drawings. … So this is just ink on acetate, and I have all of these drawings, I just never figured out how to show them.

I got this cheap frame from Blick. I’m going to make a mold of this frame … and then pour epoxy resin into the mold. Essentially going to make a clear frame. And the image will be kind of floating in the middle of the clear resin. So it would be like glass, a little spacer, and then have the image sort of float at the back. And everything’s clear. I don’t know if it’s going to work, but we’ll see.

Edited for length and clarity.

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Art Exposed: Jodi Connelly

Meet the artist who uses dirt to explore the connections between people and the environment

Burnout from a 10-year career working in the nonprofit sector in Brooklyn led Jodi Connelly to a creative breakthrough in her art practice.

Art Exposed: Tracy ‘Indi’ Carlton

Meet the Amador County artist who traded in a 21-year nonprofit career to become a creative expression coach

Tracy Carlton took an unconventional path to her art career, launching a as a creative expression coach and teacher last year following a 21-year career at First 5 Amador, the Amador County branch of the statewide nonprofit commission dedicated to improving early childhood development.

Art Exposed: Carrie Hennessey

The vocalist, instructor and writer emphasizes positive energy and risk-taking, whether onstage or coaching others

Carrie Hennessey has been known to belt out a tune while walking her dogs outside of her South Natomas home, but the neighbors in this otherwise quiet neighborhood don’t seem to mind. She picked up the moniker “Opera Mom” while her two children (now in their 20s) were in elementary school, but there is a lot more to her.

Art Exposed: Betty Nelsen

On the art of how to look in the mirror

In revisiting her early self-portraits, Betty Nelsen has zeroed in on the strongest elements, cropping the drawings into pages that will go into a series of handmade books.

Art Exposed: Beti Masenqo

The musician-singer-songwriter blends folk and rock with the Ethiopian songs of her childhood

When she performs, singer and songwriter Beti Masenqo leaves this earthly plane in a way that seems entirely effortless.

Art Exposed: Unity Lewis

A curator, artist and musician carries the legacy of his grandmother’s groundbreaking work documenting the Black experience

Unity Lewis recently curated a series at Crocker Art Museum that brought his grandmother’s book into the three-dimensional world by pairing works of artists from previous generations with their modern counterparts who will carry the torch.

Art Exposed: Vincent Pacheco

A graphic artist blurs art and design and plays with the cultural language of piñatas

The artist builds piñatas in various forms of cultural artifacts. Each is a temporary monument to family, identity and cultural heritage.