Davis artist Betty Nelsen’s sense of humor is practical but sly: “I’m really good at finding other people’s words, but not so good at finding my own,” she joked in an interview after searching for the right descriptor.

Nelsen is in the middle of some major life transitions at the moment. She taught her last art class at American River College and had a solo show at the college’s Kaneko Art Gallery in which she gave a public lecture entitled “Motivation, Intention, and Process.” She’s constructing a series of artist books for an upcoming show. Nelsen is also downsizing from a large home in Davis and preparing to move into a Buddhist-inspired community in Northern California where she plans to live out the rest of her days among other artists and retired academics. She faces this next phase with the same bravery she applies to her art.

When she graduated from high school in St. Paul, Minnesota, Nelsen’s father told her he’d pay for college, but only if she studied something real, not art. She decided to go art school anyway, with or without help from her parents. Her art education brought her to UC Davis for graduate school, and one project she started back then just came full circle now, 40 years later.

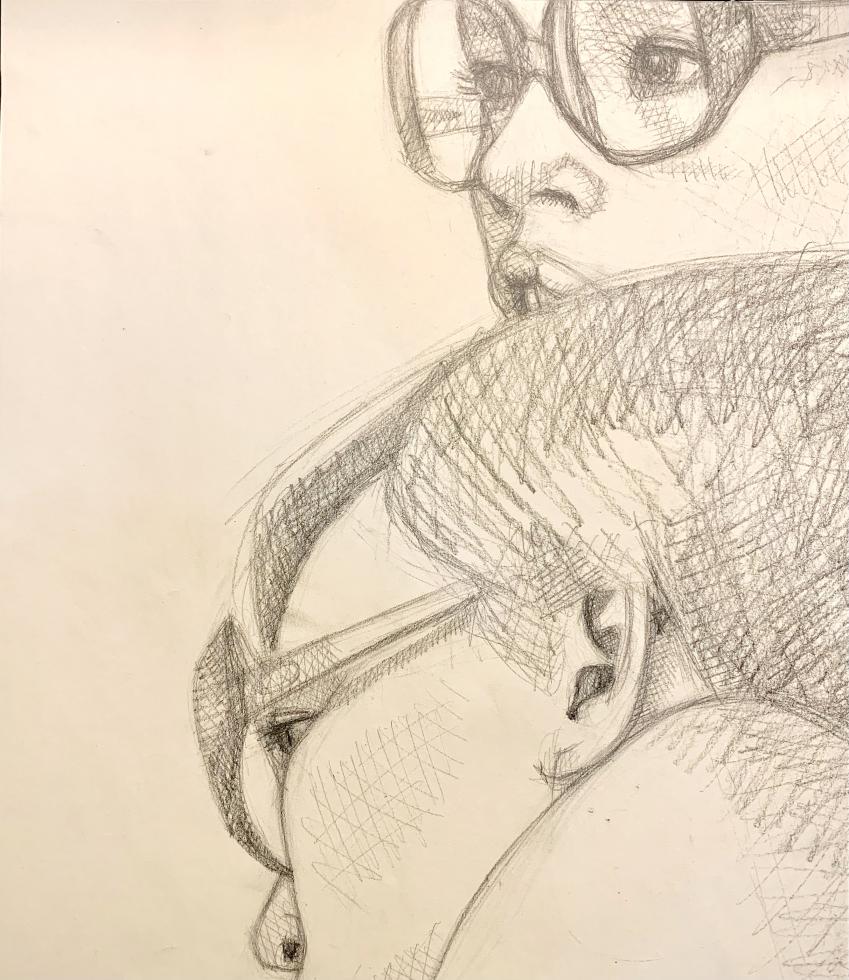

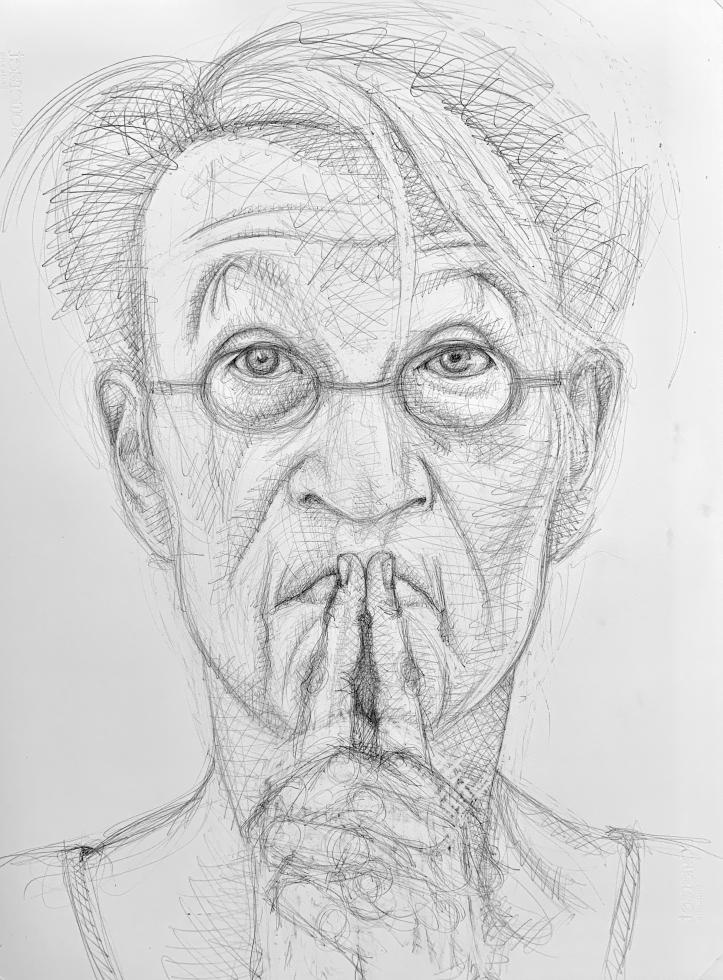

During her MFA program, she began a series of self-portraits, graphite on large newsprint. The portraits are wrought with both precision and a wildness, sometimes with complex emotions playing on each of her faces.

During her MFA program, Nelsen began a series of self-portraits.

Then right before the pandemic, she came back to the pencil, the mirror, and herself as the subject. During the 2020 election, Nelsen’s posts of her progress on social media were cathartic gold: outrage, confusion, exhaustion.

In revisiting her early self-portraits, she has zeroed in on the strongest elements, cropping the drawings into pages that will go into a series of handmade books. She has magnified her control over her lines and shading. Some body parts become abstractions. Each book will be an accordion, unfolding the linked parts of herself on a continuum. They are a meditation on the passage of time, acknowledging the way we store memory and identity together. It’s a way for Nelsen to spiritually prepare herself for the next phase of her life.

Betty Nelsen’s artist books will be on exhibit at the CONTENT Artist Book Exhibition at the Artery in Davis, September 1-25, 2023.

Tell me about the first batch of drawings you did as a student at Davis.

That first year, I was probably doing the worst paintings I ever did in my life. I was borderline humiliated, I was doing these kind of abstracted things, some of them were kind of corny. I think I felt like I had to perform in a way. I hadn’t been in school for years, and so I was listening to everybody except myself. And in the summer, I just dropped back into my own real voice. And that was when this work started to happen. With the double self-portraits, it’s work about my relationship with myself. It’s kind of that the inner voice steps outside of itself.

And you chose to do these big — what was the objective?

I had been doing large-scale for years. I felt like the larger the drawing, the bigger the impact.

And seeing them cut up like this, I didn’t understand at the time what happens when you come in tighter — and it’s really one of the thrills about this — it’s like I’m recomposing the drawing in a way that emphasizes what I wanted to emphasize earlier, in a stronger way. Who knew I could be this excited about these drawings 40 years later.

Tell me more about the drawings as they relate to the artist book.

It’s a long process. Right now, I’m in the beginning of an idea of these self-portraits talking to each other. I have no idea who’s going to live next to who. I make a mock-up so I can see the whole book and if there is going to be a build of emotion. You know those silly arguments you have with yourself, where part of you is so vulnerable and the other part is all “Oh, you idiot,” and it’s all played out here. So I haven’t decided how the whole thing will come together. It’s nice to be a little whimsical and a little serious.

Nelsen cropped her early self-portraits into pages that will go

into a series of handmade books.

What was your idea of success back then?

I thought I’d get a gallery and sell and keep doing my work and be a full-time artist, and that didn’t happen. And there is that disappointment. It’s taken a lot to come to terms with that and accept who I am as an artist.

With my current circumstances, with moving and downsizing substantially, this project of cutting up and making smaller, I can take it with me. There is an accessibility with a book that’s different then a great big drawing. If it’s too intense, you know you can close the damn book!

The only way you can do a profile of yourself is to set up two mirrors and draw yourself in the mirrored mirror. I’m pretty adamant about not using photographs. There are a number of artists who use photographic reference really well, but I’m not one of them. I always feel confined by it. I can’t step far enough away and find myself in it. The other thing about drawing with the mirror is that the drawing becomes a compilation of multiple moments, like hundreds of moments, and it’s a whole different experience.

I’m thinking about the self-portraits you did during COVID, and how you didn’t draw for a really long time. Tell me about that progression.

Nelsen returned to self-portraits in 2020.

So then how did you return to self-portraits after 40 years?

I was beginning the semester teaching a Facial Expression and Anatomy Class. Of course, the whole time I was still teaching art. And I noticed this class in particular, they were such newbies, they had no understanding of process. So I made some drawings and took a photograph every five minutes to demonstrate process, and in the midst of that I realized the reason it’s taken so long is that I was in such deep grief for so long that I didn’t have the capacity to be that vulnerable as you need to be to go into the studio. And that was a relief. I had healed enough to do it again.

And when you came back to drawing it was like a revelation.

I couldn’t have predicted being about to jump back in with both feet. We don’t have nearly as much control as we think we do; we don’t know where the pull comes from. But when it shows up, are you going to listen? I just decided I was going to draw whoever showed up.

And now these drawings, all these “selves,” will come together in this book.

In a way I couldn’t have anticipated.

Edited for length and clarity.

–

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Art Exposed: Beti Masenqo

The musician-singer-songwriter blends folk and rock with the Ethiopian songs of her childhood

When she performs, singer and songwriter Beti Masenqo leaves this earthly plane in a way that seems entirely effortless.

Art Exposed: Unity Lewis

A curator, artist and musician carries the legacy of his grandmother’s groundbreaking work documenting the Black experience

Unity Lewis recently curated a series at Crocker Art Museum that brought his grandmother’s book into the three-dimensional world by pairing works of artists from previous generations with their modern counterparts who will carry the torch.

Art Exposed: Vincent Pacheco

A graphic artist blurs art and design and plays with the cultural language of piñatas

The artist builds piñatas in various forms of cultural artifacts. Each is a temporary monument to family, identity and cultural heritage.

Art Exposed: Alina Tyulyu

A lifestyle photographer becomes a war documentarian when she returns to Ukraine as a volunteer

The Sacramento-based photographer is traveling around her

native country of Ukraine to aid refugees during the

Russia-Ukraine war, documenting their experiences along the

way.

Art Exposed: Nancy Sayavong

The Roseville-based sculptor uses woodworking techniques for both art and remodeling

As a woodworker and metal fabricator, Nancy Sayavong uses her

training both for art and remodeling jobs. Her work is

interested in the contrast between the romantic ideal of the

home and its lived reality.

Art Exposed: Tasha Reneé

The local potter on the hazards of ceramics and making peace with impermanence

Tasha Reneé sells ceramics independently and through plant shops

and home decor businesses and is currently pivoting to teach

others through private lessons, workshops and classes.