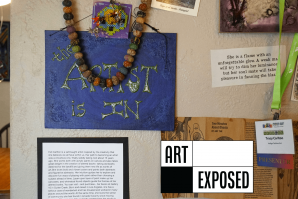

Muñoz is a Sacramento-based printmaker, zine maker and curator

who views her work as both political and spiritual. (Photo by

Marie-Elena Schembri)

Imagine spending a late morning in a quaint but colorful rooftop garden, watching shadows of flowers dance across your sun-soaked patio. A hummingbird darts from bloom to bloom, in and out of the shadows as its luminous feathers glint in the sun. Now imagine capturing the essence of this magical moment, distilling the ephemeral beauty of shadows and the flitting energy of the tireless hummingbird into one small 3 by 4-inch rectangle, rendered in black and white, each detail painstakingly carved and then slathered in black ink and pressed by palm onto sheets of semi-translucent mulberry paper.

This is the work of Jazel Muñoz, a Sacramento-based printmaker, zine maker and curator whose artwork is steeped in the beauty and wonder of nature. Muñoz creates intricate relief prints of subjects like praying mantises, fungi, birds, butterflies and flowers from her DIY home studio, using her hands, a spoon or a small press to create works ranging from palm-sized to 18 by 24 inches. She also creates zines ranging from simple to elaborate, with some involving multiple steps including hand illustration, collage, digital manipulation and printmaking.

A 34-year-old Folsom native, Muñoz studied art, printmaking and photography at Folsom Lake College and Sacramento City College before transferring to the University of California at Santa Cruz to earn a bachelor of arts degree in printmaking.

Since moving to Sacramento in 2017, Muñoz has immersed herself in the local art community, organizing several printmaking and zine events, including co-coordinating the inaugural Latino Center of Art and Culture’s Zine Fest in May and highlighting local art as the WAL (Warehouse Artist Lofts) Public Market Gallery curator since January 2023, where Muñoz is also a resident. She also teaches art at Work of Art, an art studio for adults with developmental disabilities operated by 501(c)(3) nonprofit Southside Unlimited, where she has worked for the last seven years.

For Muñoz, a Chicanx queer artist, it is important to provide opportunities to creatives from marginalized communities, which she also prioritizes in her curation at WAL.

“Sober Whys and Sober Highs: Q&A for Our Alcohol-Free and

Sober-Curious Friends” is a zine that answers some of the

questions people often ask Muñoz about her sobriety. (Photo by

Marie-Elena Schembri)

“I have really been focusing on marginalized forces, BIPOC and queer folks. The last exhibition that I curated was a queer youth artist exhibition, and a lot of the folks are often emerging artists, or this is their first ever. They’ve been creating work but haven’t had a space where they felt either it’s felt like they could see themselves in, felt welcomed or honestly just been kind of seen,” Muñoz explains.

For Muñoz, art is political. Inspired from a young age by her family’s extensive book collection and early exposure to political art by artists like Emory Douglas and images of the Black Panthers, Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Mexico, Muñoz curates and creates with both passion and intention.

A zine that Muñoz created in collaboration with a friend, CK, titled, “Sober Whys and Sober Highs: Q&A for Our Alcohol-Free and Sober-Curious Friends,” addresses the discomfort others can feel when their friends or loved ones become sober. Fielding common questions about their lifestyle choices, the two friends created the zine as a playful yet informative guide to those wondering things like, “What do you do at parties?” and “Have you saved a ton of money?”

“Magical Being” is one of a series of prints featuring the

hummingbird, a symbol for Muñoz of the connection to loved ones

who have passed away. (Photo courtesy of Jazel Muñoz)

By not spending money on alcohol, Muñoz says she has “been able to redistribute this money into the community.” Rather than buying drinks while out at an event, she is able to buy band merch or art from local artists. “That feels rewarding and feels much better as a way that I want to redistribute my money,” says Muñoz, who also sees her sobriety and veganism as political choices.

Muñoz chose to become sober after the loss of her father in 2019, and she explores both her grief and spirituality through themes of nature in her art. Her series of hummingbird lino block relief prints were inspired by family lore that hummingbirds are “messengers from the beyond.”

“Seeing something like a hummingbird can make us feel almost closer to a loved one. And also it brings joy. … If it’s around my dad’s death anniversary or birthday, or I’m in a place where we shared together, I will often see a hummingbird. And so I wanted to create a series to kind of honor that, to explore it and kind of maybe hold onto that connection that I had,” Muñoz says.

She describes hummingbirds and butterflies, which also show up in her art, as “free spirits” that can’t be held captive.

“It’s like these little magical beings that we can’t hold onto. So they’re fleeting, which is, I think, also symbolic of life. Everything is fleeting. I think through relief printing linocut, it’s kind of allowed me to almost relinquish some control and let go through this process.”

How were you exposed to political ideas and art at a young age?

My dad was a very avid reader, and I felt like he had everything as far as content for books. We had lots of books in the home. We’d visit the library — all we had was PBS — and I feel like because of his interest in world matters and was also just socially political. And then, of course, my siblings.

My oldest sister actually studied communications and had some interest in journalism, so there were books that I was seeing that were college-level or things that were being introduced. And because of music too, my interest in punk music and a lot of, I guess it would be rock music. Rage Against the Machine was somebody that I listened to in junior high; a lot of their lyrics spoke to things.

Do you think part of it is because of your Chicanx culture?

I will say yes. It definitely inspired that. I think a lot of it was culturally, so having that influence at home and learning about the Zapatistas in Chiapas Mexico, and then there’s obviously

Emiliano Zapata, who is also a revolutionary, who I would also see his image. So individuals like that.

I was learning who they were and also still forming my sense of self, but I was also very spiritual. I was really interested in Eastern philosophy and Taoism and Buddhism and kind of just this idea of duality, some of the things that we experience in life, but also our beliefs and my interests. So it was just a lot of influences from different places, I feel like.

Do you think that idea of duality shows up in your work?

I believe now, in the work that I’m conveying, it is more like non-dualism. … It’s kind of taught in Western thought, is there’s the dualism, there’s one or the other, and that exists in a lot of other ways too, in gender and religion and stuff. So I kind of was like, “OK, I don’t really fit in either-or.”

In “Spirits of the Saguaro,” one of Muñoz’s largest prints at 18

by 24 inches, intricate details emerge from hours of careful,

meditative carving. (Photo courtesy of Jazel Muñoz)

I think that the impression from my understanding is everything is connected, and it’s also not linear. And so, I think in my work, I like to pull from my personal experiences. And as I had mentioned, my dad passed in 2019, and so having been able to move back and having some inkling that my dad’s health wasn’t great was also a push for me to be like, “Okay, he wants me closer to home. I want to be closer to home.” And then experiencing that loss, which was very much drawn out over a period of two years. And in my youth and in college, I have lost friends, so I wasn’t unfamiliar to grief.

I think I started contemplating and looking at nature and how things are constantly growing, blooming and then wilting, dying, and then it’s decomposing, and then that provides life again. And so I would kind of ruminate on these facts, I feel like, and it helped me.

Do you mind telling me why you chose to go sober?

Yeah. So I think I kind of had gone through periods of on-and-off drinking. And I think that I got to — it was two things — one of them was that I got to a point where I felt that drinking wasn’t giving to my life. I felt that I was often distracted by it and I didn’t like the spaces that I was in that were involved in drinking. And I felt like I wasn’t really creating authentic connections or relationships. So that motivated me certainly. And then the second reason is when my dad passed, I think the first year after he passed, I didn’t know what to do with myself.

Muñoz demonstrates how she captures shadows from plants in her

garden by tracing them onto her block before carving. (Photo

courtesy of Jazel Muñoz)

It was in 2019 and then the pandemic happened. And so I think in that span it felt like I could easily numb myself through drinking and avoiding the feelings of grief that way. And so in that I reflected and was like, this is not what my dad would have wanted. And he also was someone who didn’t drink. And so I was like, I want to honor him and myself by actually processing these feelings, as painful as they were and are at times, right? And so that pushed me even further. I was like, okay, I am going to do it, and I have more reason to now because of my dad. So I’ve stayed sober.

Do you think your sobriety has influenced or changed the way that you make art?

I would say yes, I feel that it has. Prior to being sober and creating work, I kind of think that what I was reflecting at the time was the turmoil that I was internally experiencing. So not being sober and having an outlet that at the time would be to be social and drink and then bring that to my art. I felt like I was still trying to find the connection there.

Muñoz’s work explores concepts of life and death, like in this

print titled “Death is Certain.” (Photo courtesy of Jazel Muñoz)

So I feel like I have a much greater understanding of what that is now compared to when I wasn’t sober. I felt like I was just very foggy, making work, feeling disconnected and knowing that there was something there. I was being pulled to express myself in this way, but still feeling a little not sure. So I would experience moments of feeling centered and rooted through my art practice, but then that would kind of vanish. It would slowly dwindle or go away. Being able to create work now, sober, I’m fully present, I think, and aware in life.

Being as involved as you are in the Sacramento art community, what are your hopes for the future of this community?

I’d hope for accessible art opportunities that reduce the barriers that many artists with disabilities face, like entry fees, lengthy applications or having previous exhibiting experiences. I hope for artists and curators to be compensated for their work, which includes more resources to receive funding that isn’t a reimbursement process. Pay artists for their work now, not later. And most importantly, affordable studio spaces for artists.

Edited for length and clarity.

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Art Exposed: Doug Winter

Elk Grove photographer creates images exploring perception and memory through the lens of visual impairment

After suffering a stroke in his right eye in 2012, Elk Grove resident Doug Winter, a trained commercial photographer, began to think differently about sight and perception.

Art Exposed: Muzi Li Rowe

This mixed media artist and photographer explores culture through defunct technology

Whether it’s layers of tiny microchips or rows of dead batteries, each work in Muzi Li Rowe’s Magical Thinking series is like peering into a tiny museum where the most microscopic parts of now-defunct personal technology devices, from old Nokia flip phones to disposable cameras, become individual hallmarks of consumer culture.

Art Exposed: Jodi Connelly

Meet the artist who uses dirt to explore the connections between people and the environment

Burnout from a 10-year career working in the nonprofit sector in Brooklyn led Jodi Connelly to a creative breakthrough in her art practice.

Art Exposed: Tracy ‘Indi’ Carlton

Meet the Amador County artist who traded in a 21-year nonprofit career to become a creative expression coach

Tracy Carlton took an unconventional path to her art career, launching a as a creative expression coach and teacher last year following a 21-year career at First 5 Amador, the Amador County branch of the statewide nonprofit commission dedicated to improving early childhood development.

Art Exposed: Carrie Hennessey

The vocalist, instructor and writer emphasizes positive energy and risk-taking, whether onstage or coaching others

Carrie Hennessey has been known to belt out a tune while walking her dogs outside of her South Natomas home, but the neighbors in this otherwise quiet neighborhood don’t seem to mind. She picked up the moniker “Opera Mom” while her two children (now in their 20s) were in elementary school, but there is a lot more to her.

Art Exposed: Betty Nelsen

On the art of how to look in the mirror

In revisiting her early self-portraits, Betty Nelsen has zeroed in on the strongest elements, cropping the drawings into pages that will go into a series of handmade books.

Art Exposed: Beti Masenqo

The musician-singer-songwriter blends folk and rock with the Ethiopian songs of her childhood

When she performs, singer and songwriter Beti Masenqo leaves this earthly plane in a way that seems entirely effortless.