The train slowly rolled toward us from about 100 feet away. We stood beside the track, and I gazed down at the approaching white headlights. The Siemens employees at the manufacturing facility talked about electrifying the tracks to test high-speed rail onsite, and I scribbled down their words in a notebook. As the small train crept closer, gliding along the test track, I gritted my teeth and recoiled into my notes, realizing it probably wouldn’t stop until it passed us.

It was September 2014 in south Sacramento. Siemens Rail Systems, a German rail manufacturer, had invited me, a Sacramento journalist, to tour the site and to help them make a pitch to the California High-Speed Rail Authority. Siemens wants to build the nation’s first true high-speed rail. I had hoped that touring the manufacturing plant would help me conquer a fear of trains.

The two employees went on about how high-speed trains could be constructed in a factory built on an empty lot beside the current plant. The small train rolled by. I smiled, pretending not to re-live a nightmare, then looked back down at my notes.

With each interview I conducted and report I filed, I sought to understand how these great rolling machines had destroyed the person I used to be and killed the person I cared about most.

For the previous two years I had learned everything I could about high-speed rail while covering California’s project for both Comstock’s and later the Sacramento Business Journal. Helping people understand how and why a sleek locomotive would whisk passengers across California’s dusty inland was my vocation. I published thousands of words on the topic.

The reporting took me into the homes of Central Valley farming families as they plotted litigation against the California High-Speed Rail Authority. I also traced the family history of its CEO Jeff Morales for a profile, listening as Morales’ brother Christopher cried over the phone as he described what it was like to tell Jeff in 2003 that their father, George, had died of a stroke.

Related: The Conductor

These sources connected to the train project were unaware of an ulterior motive in my reporting. With each interview I conducted and report I filed, I sought to understand how these great rolling machines had destroyed the person I used to be and killed the person I cared about most. But publishing stories about high-speed rail never helped. Like other pain relievers, print journalism became one more way to avoid facing what happened that day.

My mother and I awakened early on Christmas Day 2008 to go skiing in the Sierras, but a blizzard kept us stuck in traffic until early afternoon. Mom and I arrived at the ski resort in Truckee too late to make even a half-day pass worthwhile. I grew frustrated but my mom, Sydney Parks, told me to “relax my brow.” That was her phrase whenever she saw me fret. When I was little, she would gently slide her thumb across my forehead, wiping my worries away. She raised me, her only child, as a single parent.

We were about to begin the three-hour drive back to the Bay Area, but outside the resort we noticed a family hiking in the snow along a hill and decided to get out to stretch our legs. We started down a path beside the road. The other family was no longer in sight. The air was fresh and peacefully still. As the snow fell over us, Mom asked me whether it was true that no two snowflakes are identical; I told her I didn’t know. The snow under my feet looked uneven, and I kicked it until my foot hit metal. We were at a train crossing. I told my mom but she kept walking. I presumed she heard me. I considered whether or not to follow her or call her back. It was Christmas Day; everything was shut down. Ice and snow were packed over the tracks. The idea of a train rolling by seemed unrealistic. We set out along the tracks, which provided a small trail between a hill to the right and a creek on the left.

When we were a couple hundred feet past the crossing, a plow train rounded a curve and charged toward us. Waves of snow spewed from both sides of its colossal grill. A yellow spotlight glared from the helm. We had seconds to clear out. We started to run, but mom fell on the tracks and moaned in panic. As I grabbed under her armpits to hoist her to safety, we were both struck by the dark mass of steel.

Eight years after his mother died, journalist Allen Young

returned to the spot where the two spent their last moment

together. At the time of the accident, the tracks were covered in

snow. To the right of the tracks, snow had been plowed to make a

5-foot-high wall, Young said. To the left of the tracks is a

steep precipice, with a creek below.

Chips of snow swirled around us like shrapnel as the dark train roared overhead. I remember being seized by an overwhelming blackness, but it’s the sound — not the image — that lives on in my memory: a chugging drumfire of turning wheels and screeching brakes. If I close my eyes to imagine it, my right arm begins to tingle. The collision cracked the bone below my shoulder in half.

The impact threw Mom about 25 feet up the hill. I was knocked a few feet from the train, and landed face down in the snow. As the train came to a halt behind us, I tried to lift myself out of the snow but realized my right arm was useless. The skin around it felt like a jacket sleeve that I could twist around in. I let the arm fall and then noticed my right foot was also broken. I slid across the snow toward Mom with my left arm and leg. She was on her back, her body contorted. When I reached her, she slowly blinked her eyes and opened and closed her mouth. Skin around her lips was gone, exposing teeth. She looked like she was trying to talk, but didn’t make a sound.

The train slowed and stopped. All I could think was that we would somehow get out of this, no matter how bad it was. We’re going to be OK. I repeated those words out loud, over and over, as we waited for the ambulance to arrive. We’re going to be OK, and I will take care of our family. I’m going to be OK, I said. We’ll be OK. I’ll take care of our family. But by the time the ambulance arrived, Mom had stopped moving. The paramedics pronounced Sydney Parks dead. She was 59.

***

I awoke on a hospital bed. A young doctor walked up and explained that surgeons had operated on my arm, which was now wrapped in gauze. The arm didn’t hurt, but my right foot did. It’s too swollen to operate on, the doctor explained. The bone shattered in the accident, he said.

“Will I ever walk again?”

He frowned. “I don’t know,” he said.

I spent New Year’s Day in the hospital and underwent two foot surgeries. After the first operation, a surgeon confirmed I would walk again, but possibly with a cane, and maybe no more hiking. A few weeks later, during a return visit to the hospital, the surgeon told me to expect a full recovery. I laughed and pushed my left palm into my cheeks and wiped away tears.

On March 19, 2009, nearly three months after the accident, I rolled through the front door of work in a wheelchair. I had only worked at the office a short time before taking leave, so most of my coworkers were still vague acquaintances. Out of respect, the wheelchair was ignored, as were the metal braces over my right arm and the black hospital boot covering my foot.

My job, at 24 years old, was to help write a daily newsletter about statewide education policy called the Cabinet Report. My employer, a school consulting firm named School Innovations and Advocacy, had hired journalists to produce an education news product. I was grateful to be paid to write.

Daily journalism became another pain medication in an arsenal that included hydrocodone and diazepam. The emotional distance between reporter and subject kept me numb; the act of writing provided an escape. It was addicting. You quiz people about their lives and their work, and sometimes they open up about life-altering failures or personal losses. But they rarely turn questions back on you. Reporters scavenge for conflict and despair, and rarely reciprocate. The job conditions you to greet everyone as a potential source, not a friend. This is how I learned to excel in my trade: stiff, dispassionate, ghost-like. My job was to write about the world in front of me. Nobody expected me to participate in it.

After a December 2008 accident, Allen Young was told he may not

walk again. He took his first steps out of the wheelchair the

following April.

In those first few months back at work, I would talk on the phone all day from my wheelchair, often cracking jokes with people on the other line. They didn’t know about the cast over my arm or the black hospital boot. I was an actor playing the person I used to be. After work, I took anti-depressants and drowned my brain in television. Who was this guy who had failed to save his mother from an oncoming train? I didn’t care to know him.

I was living with a friend’s parents in Rancho Cordova. I spent much of the evening in bed, staring at my black hospital boot, which had to be elevated. Still, the foot would swell with blood and pain. It only slightly resembled the other foot. Even without the swelling, the reconstructive surgery had left the foot bigger, rounder. A scar lined its side. I hated my foot, but a loathsome voice in my head welcomed the pain. It was my punishment for not saving her. I deserved this.

I’d lay in bed and ruminate over every decision I made the day Mom died. Had I done anything differently — anything — she would still be alive. We would both still be alive. That was a comforting thought I adopted early on: imagining us dying together. The medics would have cleared my body away before it could soak in all this guilt. The snow-covered hills would remain a place of beauty.

On a sunny day in April 2009, I took my first steps out of the wheelchair… Learning to walk is glorious.

“Relax your brow,” Mom would say.

And yet despite the dark fantasies, my body continued to heal. On a sunny day in April 2009, I took my first steps out of the wheelchair. I clutched a metal cane, stood up and strode a couple steps down the hallway. My caregivers cheered. Nerves rattled my foot as pain seared through my leg, but I was walking! I had spent months envisioning this moment. Imagine if you could remember taking your first steps as a toddler. Learning to walk is glorious.

After a couple weeks I could walk without a cane, and my editor assigned me to enter the State Capitol and report on legislative committees and press conferences. I was one of the reporters shouting questions at Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger as he ducked and tumbled from one talking point to another. The events were thrilling. They also provided a convenient narrative to friends and family that I was overcoming my ordeal with strength and enthusiasm.

Journalist Allen Young interviews Mayor Darrell Steinberg as a

reporter for the Sacramento Business Journal.

My friends all lived outside of Sacramento, so I’d write them funny tales of covering the Governator. My entire support network — a collection of Sydney’s friends and my childhood friends — rooted for my success. My attitude was integral to my mom’s legacy. I had to act happy or else I feared I’d let everyone down.

At times I would forget to dissect my own happiness and just live it. It was during one of those casual moments that I met Lily in the State Capitol. We exchanged business cards and went to lunch a week later. Lily worked in education and cared deeply about helping young people, but she could also make fun of her own convictions and the strange values of people in politics. We’d laugh to tears. I never went into detail about the accident and she didn’t pry. We married in 2013, and every day with her is a gift.

One day while walking back from the Capitol, I crossed over light rail tracks as a train approached from afar. Though the train was moving slowly and I had plenty of time to move to safety, I panicked and ran into an alley. Clutching the handle of a green dumpster, I cried for about five minutes, before walking back to the office.

***

Those post-traumatic episodes still happen, though they are less intense and less frequent with each passing year. This last Christmas marked eight years since the accident. I’ve grown accustomed to chronic pain in my right foot — as much as anyone can — so I pivot to the left when standing. Doctors say the pain will just get worse with age. Violent memories are still a burden. I’m still cycling through different therapies. Reporting on California high-speed rail never produced any revelatory capstone, except that the project appears doomed.

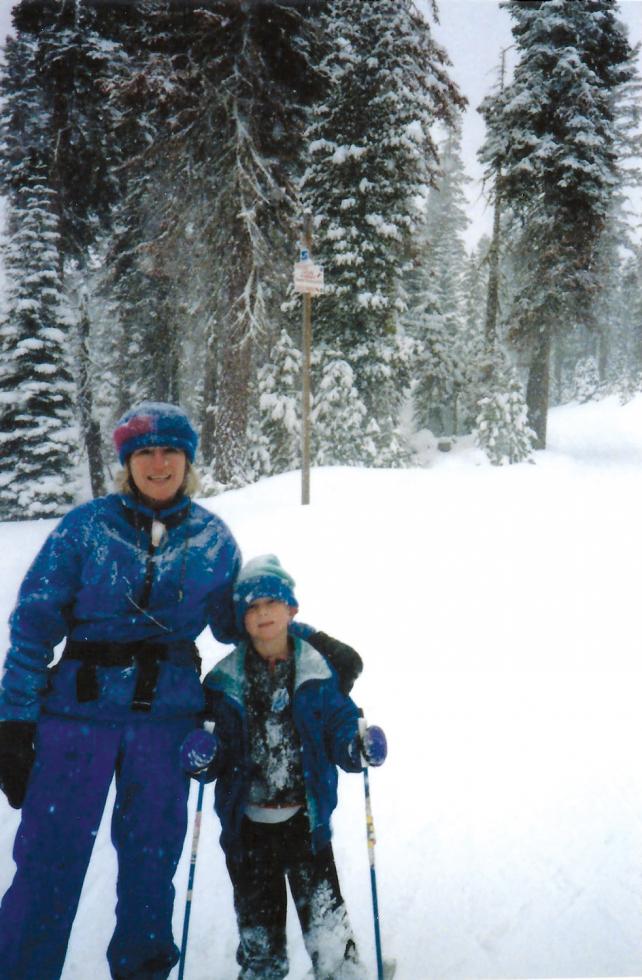

Allen Young with his mother, Sydney Parks, on a ski trip in 1994.

He was 10 years old. His mother was a single parent.

I wish I had a moral to tie up my story, a mantra to live under. Some inspirational quip about survival. I’ve rotated through encouraging messages, but over time the meaning evaporates into a dishonest quote. You gain wisdom and lose it again, even if you write it down. But after a number of years, you can attain a clear picture of the person you used to be and realize you’ve moved forward.

In those initial years of recovery, my body continued to heal on days that my mind gave up. Muscle grew over the metal pins affixed to my humerus bone. The swelling in my foot always subsides; my heart continues to beat. My being, whatever it is, wants to survive.

“Relax your brow,” she’d say.

Post-script

This story is dedicated to my wife Lily, who sat with me on numerous Saturday evenings after I returned from my writing desk, a stricken look on my face after reliving the incident and its aftermath. On days I could barely talk, she shined at me.

It took eight years to write this story. For the first five years I couldn’t talk about what happened, even to friends. I began the piece in fall 2014, under the presumption that turning the incident into a commercial product would present feelings of power over the depicted events. Ultimately, the publishing mattered little. The act of writing helped me turn a corner. Whatever the trouble is, you’ll feel better after putting it down on paper.

Comments

A very wise man once told me, "we are all living with something"!

The stories may be different but we all have one or two or three... and it is Okay!

one of the best humans i've ever met. thanks Allen. love ya buddy.

Thank you, Alan, for sharing your traumatic, real, and inspiring life event. I've known Lily since she was young. To have a glimpse into your life, of a most vulnerable time and experience, brings me closer to knowing you as a couple. It seems odd to combine a personal response with a public article. I'm sure I share for many; although this story is one of recovery and healing for you, it is a reminder of how the human spirit and drive for life takes over and thus brings us to the other side of healing. That other side is survival and understanding who we are meant to be, to recognize the gifts we have been given, and appreciation of who and what's important in our life. Thank you, Alan.

Heart-wrenching, beautiful writing about a terrible, life-changing (and tragically life-ending) event, by a talented young writer I was privileged to mentor/edit in the UC Center-Sacramento's 2007 summer Public Affairs Journalism Program. I didn't know Allen's wonderful mom, who died the following year, but I felt I knew her, from his loving, often funny, always compelling stories about her. And I know how difficult it was for Allen to write this deeply moving article, which he had occasionally talked w/his teachers/editors/mentors about writing, struggled to write, over the past 8 years. . .After reading an early version, one prescient editor said he "wasn't ready" to write it yet, but he would be. We knew he would be. And his amazing Lily helped make this beautiful article, and Allen's recovery, his catharsis, possible. I am honored and humbled to have been asked to play even a small part in this gifted young writer's tortuous -- and ultimately, cathartic --journey. Your mom would be so proud, Allen.

As far as I could see, Allen spent some time with his dad and my friend Roger Young, pre and post tragedy, and yet there is not one comment about Roger in this fine essay.