The rapid growth of deadly fentanyl across the U.S., California and our region is shocking. It is now the leading cause of death in the U.S. for adults ages 18-49. The growth has been so rapid that many people still aren’t aware of this synthetic drug and how it can kill so easily and rapidly. Fentanyl is falling into the hands of teens and young adults who think they are taking a Xanax or Percocet to relax but instead are taking a fake pill that can kill them within 10 minutes. Comstock’s produced this Special Report to bring awareness of this deadly drug, so you can alert your children and friends of how One Pill Can Kill.

- Judy Farah, Editor

Ground zero of the fight against perhaps the most dangerous drug to hit the Capital Region in recent years is a place like Walter’s House in Woodland.

Already, staff at the residential treatment program has seen increasing amounts of opioid use in the past four years among people seeking treatment, according to Doug Zeck, executive director for Walter’s House and a related program that helps people experiencing homelessness, Fourth & Hope. In the past 3-6 months, many opioid users have been coming in having used fentanyl.

“It’s the biggest crisis we have right now,” says Lori Miller, substance use and prevention division manager through Sacramento County’s Department of Health Services.

“It’s the biggest crisis we have right now.”

Lori Miller, substance use and prevention division manager through Sacramento County’s Department of Health Services

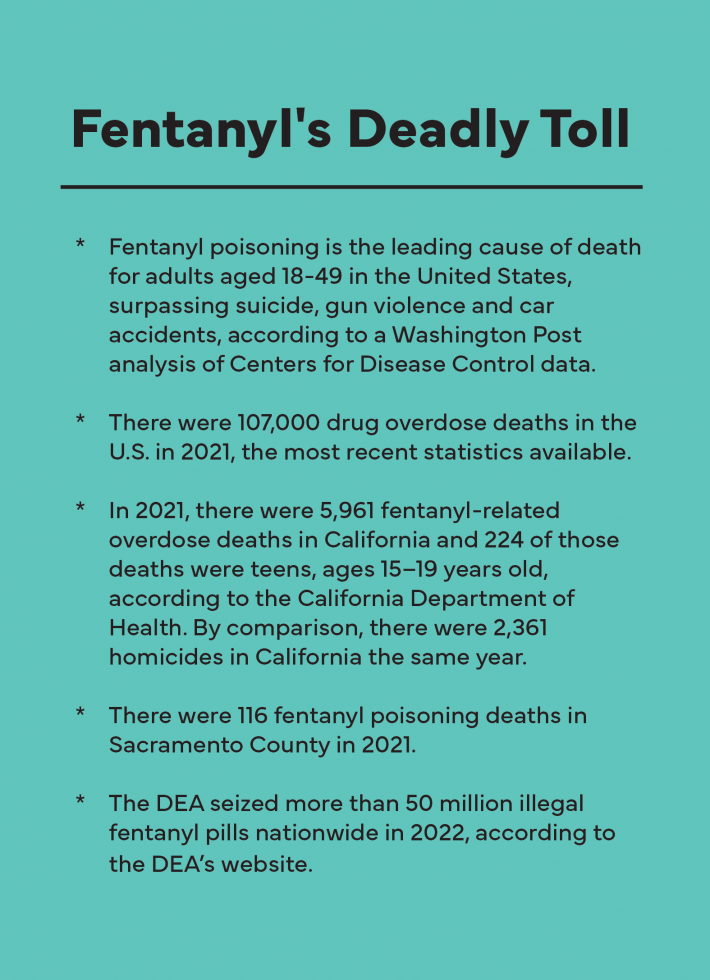

All over the Capital Region, public health officials, lawmakers and law enforcement are gripped with the crisis, fighting a drug that is easily available and able to kill in doses as small as 2 milligrams. And sadly, fentanyl is causing a soaring death rate in teens. In 2021, there were 224 fentanyl-related overdose deaths among teens, ages 15–19 years old, in our state, according to the California Department of Health. But there is also hope, with this coalition and others fighting back against the deadly drug.

An emerging crisis

Fentanyl didn’t start off simply as a public health scourge. The drug is regularly used by doctors as pain relief for patients and in anesthesia. “It is a great pain medicine,” says Daniel Colby, a specialist in emergency medicine, medical toxicology and addiction medicine for UC Davis Health. “If you break your femur, you probably want fentanyl or another opioid like that, at least short-term to get you through the pain. It hits opioid receptors in your body and relieves pain.”

But now fentanyl poisoning is the leading cause of death for adults aged 18-49 in the United States, surpassing suicide, gun violence and car accidents, according to a Washington Post analysis of Centers for Disease Control data. The CDC also reports that there were nearly 107,000 drug overdose deaths nationwide in 2021. That year, there were 116 fentanyl poisoning deaths in Sacramento County, according to the county’s public information office. (Statistics for 2022 aren’t publicly available as of this writing.)

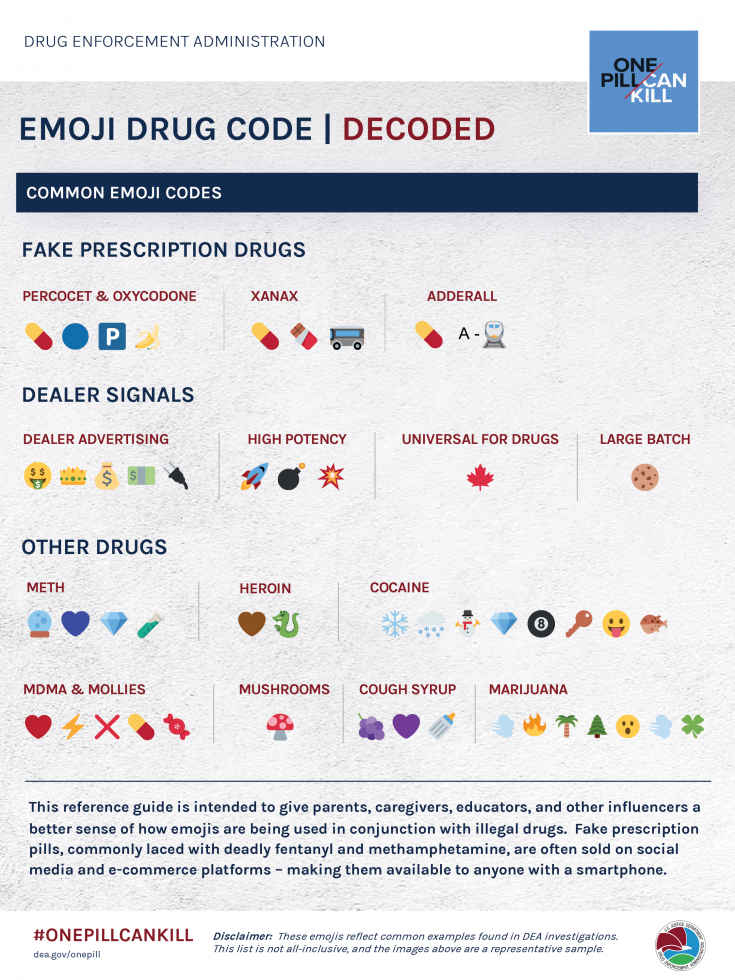

The problem has been a sharp rise in the availability of illicit fentanyl, or fake pills, which has shown up in everything from Percocet to Xanax, methamphetamine and marijuana. The crisis comes when a user, possibly a first-time user, doesn’t know the pill they are taking is laced with a deadly dose of fentanyl.

The highs can come with a terrible cost, even with a small amount of fentanyl.

“As dosing goes up, when you get more and more, people get more and more sleepy and their respiratory rate, their breathing rate goes down,” Colby of UC Davis says. “If you fully overdose, you get completely sleepy, you get somnolent and then your respiratory (system) can go down so far that you stop breathing. And that’s how you die.

Many officials interviewed for this story pointed to methamphetamine, which has long wreaked havoc, as the No. 1 problem drug in the Sacramento region. But many say fentanyl is just behind. And all over the region, officials are using a word to describe what fentanyl is creating in their communities: crisis.

“The root of their addiction, it could be past trauma, different things like that,” Zeck says. “But I think once they’ve been using opioids, now they’re looking for something that’s more. And so now it’s the teaching and the developing their understanding around the danger of fentanyl is what our counselors are having to take on.”

The illicit fentanyl pipeline is well-known among law enforcement, yet still highly effective. Precursor chemicals for fentanyl are manufactured in China and imported to the Jalisco New Generation and Sinaloa cartels in Mexico, which produce fentanyl powder and counterfeit pills. The powders and pills are then smuggled into the United States and distributed through an assortment of street gangs and dealers, according to the United States Drug Enforcement Agency. In January, President Biden traveled to Mexico to discuss how to combat the flow of fentanyl into the U.S. with President Andres Manuel López. And during his budget address last month, Gov. Gavin Newsom dedicated $97 million to the fight against fentanyl.

“It’s really exploded in the last few years,” says Bob Beris, acting special agent in charge of the San Francisco division of the DEA, whose office covers Bakersfield to the Oregon border. The DEA seized more than 50 million illegal fentanyl pills nationwide in 2022, according to the DEA’s website.

Sometimes, law enforcement agencies have been successful in making arrests along Interstate 5, such as when the U.S. Attorney’s Office announced charges in October against 11 people in Washington state and California suspected of trafficking “more than 1,000 pounds of methamphetamine and hundreds of thousands of fentanyl pills,” according to a press release.

But the cartels persist because, as Beris explains, they can create pills for literal pennies and sell them sometimes as high as $60 to $80 apiece.

“These organizations are going to go wherever they can create money,” Beris says. “They don’t care about people’s safety, they don’t care about whatever, so if their pills are poisoning people, they don’t care. You’re a product to them and they want to get their product out to as many people as possible.”

Fentanyl gets distributed by a network of street gangs and dealers who reach users of all ages, including young people. Dr. Rob Oldham, Placer County health and human services director and interim health officer, says half of all fentanyl deaths in the county in 2021 were among people aged 25 and younger. (Placer County had 50 opioid-related deaths in 2021, according to the California Overdose Surveillance Dashboard.)

Lauren Werner, program manager for the Sierra Sacramento Valley Medical Society, which oversees the Sacramento County Opioid Coalition, sees how younger users can fall victim to fentanyl.

“I think one of the main things that makes the fentanyl crisis is the popularity of counterfeit pills that look legitimate,” Werner says. “There’s a lot of kids that have been experimenting with getting these pills off Snapchat, off Instagram, TikTok.”

It leads to sometimes heart-wrenching outcomes, such as that of 17-year-old Whitney High School senior Zachary Didier, who fatally overdosed in December 2020 after taking a fake Percocet pill. His mother, Laura, now speaks to students at local schools about the danger of the drug. (See sidebar.)

“It’s just a horribly tragic loss of life,” says Rocklin Unified Superintendent Roger Stock. “I think it really opened a lot of people’s eyes to just how severe the fentanyl issue is.”

Fighting back

Placer County law enforcement caught a break reviewing Didier’s cell phone and were able to set up a fake drug buy in early 2021 with the person who sold Didier fentanyl. When Virgil Bordner was arrested, Placer County District Attorney Morgan Gire had a choice to make.

Gire’s office had never prosecuted someone as the result of a fentanyl death. It faced some questions of parsing liability between a person knowingly taking drugs — even without knowing they contained fentanyl — and the person who sold it.

“We grappled with that and ultimately came to the conclusion that if you knowingly sell what you know to be dangerous to someone else and they die as a result, you are legally responsible,” Gire says.

Bordner, who sold the fatal drug, ultimately accepted a deal to plead no contest to charges of involuntary manslaughter and sales of narcotics to a minor, receiving a 17-year sentence. Gire’s office also has three pending murder cases related to other fentanyl deaths.

“I couldn’t be more thrilled,” Rocklin Police Chief Rustin Banks says of DA Gire. “These truly are poisonings, and the fact that he’s taking the approach that he has allows us to really go after and possibly make a dent in this issue that so many communities are dealing with.”

To Gire’s knowledge, he is among the first district attorneys in the state and the only so far in the Sacramento region to file murder charges for fentanyl-related deaths, with none of those cases having gone to trial so far. Other district attorneys in the region are interested in pursuing similar charges. Yolo County District Attorney Jeff Reisig says the theory is “absolutely” justifiable.

“The analogy I would give you is currently in California law, there’s long precedent for the idea that if somebody’s convicted of driving under the influence, during that first conviction, they’re given a warning about the dangers of drunk driving,” Reisig says. “And they’re told specifically if you drive drunk again and you kill somebody, you could be charged with murder.”

El Dorado County District Attorney Vern Pierson says his office has a few related cases it’s looking at filing. It is giving what are known as Watson advisements to people who sell fentanyl, putting them on notice about its deadly effects.

Rochelle Beardsley, assistant chief deputy district attorney for Sacramento County, says her office hasn’t filed murder or involuntary manslaughter charges yet related to fentanyl, but that she was familiar with the case involving Didier’s death. “If we had a case present like that in Sacramento County, we would file that case,” Beardsley says.

Sacramento County Sheriff and former California state assemblyman Jim Cooper says the legislature is still reluctant to do penalty enhancements related to drugs. “In the role of drug sales and drug dealing, the dealers know the penalties are not very harsh at all,” Cooper says. “It’s unfortunate.”

Newly elected Rocklin-area California State Assemblyman Joe Patterson says he is authoring a bill, AB 18, to create advisements for convicted fentanyl traffickers so they can be charged with murder. A similar bill, SB 350, failed during the previous legislative session after failing to get sufficient buy-in from progressives, though Patterson is optimistic for his bill’s future.

“We’re not talking about the user of fentanyl, which may need help,” Patterson says. “We’re talking about people that are dealing this stuff to our kids. Those are the people that we need to hold accountable for bringing this into our communities.”

Not everyone supports prosecuting people for murder for fentanyl distribution. Werner of the Sierra Sacramento Valley Medical Society says she didn’t want to speak for the Sacramento County Opioid Coalition, but expressed reservations.

“There’s so many layers to the war on drugs that have failed,” Werner says. “And incarcerating people for drugs in the past has not proven to be successful to stopping the amount of people that … get hurt from doing drugs.”

Yolo County Health and Human Services Agency Director Nolan Sullivan says he worries about conservatives looking to push anti-immigration stances by co-opting the narratives around fentanyl. “It’s a public health issue,” Sullivan says. “And I think that we’re making it into a criminal issue.”

Finding solutions

AB 1542 by Assemblyman Kevin McCarty would have created a Yolo pilot program for secure residential treatment of people convicted of crimes but was vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in October 2021.

“I understand the importance of developing programs that can divert individuals away from the criminal justice system, but coerced treatment for substance use disorder is not the answer,” Gov. Newsom wrote in his veto.

Zeck, the executive director of Walter’s House in Woodland, says he understood that many of his counterparts might not have been supportive of the bill, though he offers, “I’ve had family members that would, I believe, be alive today if a program like that would have been around.”

A five-county treatment program bill, AB 1928, was introduced by McCarty in the 2021-22 legislative session and died in the Assembly.

“I think we need to look at this from all angles,” McCarty says. “I know it’s a big federal debate as well and supply coming to the United States across the border, that’s an issue. But from our perspective here in the state, it’s a problem that we need to look for innovative solutions.”

Officers around the region have been carrying the lifesaving drug naloxone or Narcan in recent years, and Patterson recently introduced AB 19 that would require all public schools in California to carry it. “Schools are obviously recognizing the importance of it,” Patterson says.

Sacramento County Unified School District Superintendent Jorge Aguilar says his board voted Oct. 10 to make Narcan available at each campus and that it’s already been used “for at least one medical emergency,” though he declined to reveal more information for privacy reasons. In his 2023 budget, Gov. Newsom allocated for overdose medication for middle and high school students. “Whatever our schools need, anyone who needs them will be provided,” Newsom said.

Different counties around the region have also begun to craft public health campaigns around fentanyl, such as Placer County’s 1 Pill Can Kill effort. Oldham says his team has reached nearly every high school in Placer County and has begun approaching middle schools with a message: Getting help is OK and resources are available, but don’t take pills that don’t belong to you.

“Basically, if you’re taking a medication, it needs to come from a pharmacy, or else you’re really playing with your life,” Oldham says.

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

The Herb Column: Cannabis Dispensaries vs. Opioid Overdoses

UC Davis professor Greta Hsu on her groundbreaking study about cannabis availability and opioid-related mortality

The study’s findings show that as the number of dispensaries increase, the number of opioid deaths drop.

Follow Her Lead: Olivia Kasirye

As the country celebrates the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, we profile 19 leaders in the Capital Region

Olivia Kasirye, public health officer of Sacramento County, is often called on to be a stable figure at the center of a crisis.

Startup of the Month: Wyllness

Granite Bay startup launches solution to help solve the opioid crisis

The opioid crisis was born in the late 1990s. Pharmaceutical companies said opioids — a class of drugs that produce pleasurable effects and relieve pain — weren’t addicting. Healthcare providers prescribed more of them. Twenty years later, we’re in the throes of an epidemic.

Hooked on Fishing, Not on Violence

A reformed drug dealer mentors youth through fishing, music and willingness to listen

Poole takes boys and young men ages 5-24 from Sacramento out every Saturday morning not only to fish but to be mentored. He calls it “healing by the water.”

Perspective: The Ever-Growing Sacramento Homeless Crisis

The closure of a 20-year-long homeless services program left a hole in our chain of homeless services, writes Sherman Haggerty in a guest column for Comstock’s. The local shift to housing first and the elimination of transitional housing have contributed to the rapid growth of our homeless population, he argues.