The sun is now California’s cheapest power source. This remarkable milestone in the changing energy economy, owed to advances in photovoltaic technology, comes as the curtains fall on the fossil fuel age.

But a complete transition to renewable energy remains many years away. While California’s leaders have set progressive goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and tapping into clean energy, it will take bright minds in the private sector to reach and realize those targets. More than half a million Californians now work in jobs related to clean energy, and among several hubs of activity, the Capital Region has emerged as a center of action.

Dozens of companies geared toward low-carbon have opened shop in the region in the past 15 years. It’s a “beehive of activity,” says Thomas Hall, the executive director of CleanStart, a Sacramento networking and educational organization for prospective clean-tech entrepreneurs. Hall feels the proximity of regulatory agencies and their staff to emerging clean-tech companies will facilitate more growth. “We’re well-positioned, and we have a lot of support from investors,” he says.

State officials seem to recognize that it will take viable companies with marketable products to realize the clean energy revolution. The California Energy Commission has made $24 million in startup cash available to promising young ventures through a funding program, the California Sustainable Energy Entrepreneur Development Initiative, or CalSEED. It provides cash for fledgling companies when private investors might still be hesitant.

“That’s the toughest money to come by — to prove a concept,” says Gary Simon, who founded CleanStart in 2005 and has been a mentor to entrepreneurs pushing new ideas and products toward the marketplace. In the past 15 years, Simon says he has watched the Central Valley’s clean-tech sector balloon from about 30 companies to 125. The Capital Region — Sacramento County and the nine surrounding counties — is home to at least 85 of them, and together they generated $3.1 billion in revenue in 2018, according to an industry analysis by CleanStart. The sector employs more than 5,000 people locally. Simon says further growth, and lowered costs associated with tapping into solar and wind power, will involve advances in storage and software.

Here are four innovative companies helping drive the revolution.

RePurpose Energy: Turning used electric vehicle batteries into solar storage

RePurpose Energy turns aging electric vehicle batteries into

solar-power storage units, more or less doubling the batteries’

lifespan. (Photo courtesy of California Energy Commission)

The first mass-produced electric vehicle, the Nissan Leaf, took to roadways 10 years ago. Now, a decade into the electrification of public and private transportation systems, their batteries — which last approximately 7-10 years — are wearing out. Like a tsunami on the horizon, these batteries are accumulating by the hundreds of thousands and pose a novel threat to the environment and a challenge for the electric vehicle industry and regulators. Because of the meticulous care that must be taken to prevent leakage of heavy metals from the batteries, recycling EV batteries is very costly.

But a Fairfield-based company envisions this potential waste stream as a resource. RePurpose Energy has developed a system of turning aging electric vehicle batteries into solar-power storage units. “We offer these batteries a leisurely retirement in a much less stressful setting than an electric vehicle,” says Ryan Barr, chief operating officer of the company and one of its cofounders.

By the end of their lifespans in electric vehicles, batteries retain about 70 percent of their storage capacity — insufficient to reliably power a car but enough to make them suitable as stationary batteries for homes and businesses. Eventually, all batteries die, but RePurpose’s system more or less doubles their lifespan. “We not only extend the life of these existing EV batteries, but we also mitigate the need to manufacture new batteries for stationary energy storage,” Barr says.

And that’s a big gain for the environment. By some calculations, producing a new solar storage battery emits as much greenhouse gas as the same battery offsets through its lifetime, making it just barely a carbon-neutral product. “You need to operate these batteries for 10 years before you get an environmental payback,” Barr says. He adds a point of irony too: While it takes a decade or more for these batteries to become carbon neutral, providers typically warranty them for fewer than 10 years.

RePurpose’s strategy is a step in the right direction. It starts with an assessment of a used battery’s health. Existing systems doing this, Barr says, can take hours.

“We use machine learning algorithms to test a battery in one minute,” Barr says.

Then, suitable used batteries are refurbished with new circuits, new controls and additional software, Barr says. When ready for market — Barr says they aren’t yet — the repurposed batteries will cost roughly half the price of a new one.

RePurpose has received several million dollars in state grant money to bring its concept to life, and early next year, the company is scheduled to fit a large local grocery store (Barr says he can’t name it yet) with 75 batteries to store electricity produced by on-site solar panels. If this test run proves the system viable, Barr says, RePurpose intends to replicate the model with customers around the state.

The economics seem to work out, and plain common sense says the RePurpose team’s business model is a great idea, but there remains a significant obstacle in the company’s path, Barr says. California Public Utilities Commission’s Self-Generation Incentive Program, which offers those who install solar panels and energy storage systems significant rebates on battery costs, specifically excludes repurposed electric vehicle batteries. “That exclusion all but eliminates a customer’s incentive to choose a cheaper, more sustainable battery system over a new battery alternative,” Barr says.

He says RePurpose is attempting to educate state officials “about the potential that will be wasted if we don’t remove this exclusion.”

Simpl Global: Making home solar batteries smaller and grid independent

Simpl Global cofounder Farid Dibachi says SimplBox can allow an

average home to go “essentially off the grid.” (Photo courtesy of

Simpl Global)

Solar plus storage is the energy combination that will one day power the world. But while solar panels are now required for all new homes in California, the storage side of the equation poses challenges. Battery systems are expensive and complicated, big and clunky — obstacles that clean-tech entrepreneur Farid Dibachi believes must be cleared for the energy revolution to play out.

His vision: Achieve in the solar battery universe what computer pioneers did with computers when they downscaled room-sized systems into lightweight, more efficient desktop PCs and mobile phones.

“I said, ‘Let’s build something that anyone with absolutely no experience as an electrician or an electrical engineer can install and operate,’” Dibachi says. “And I’m happy to say we succeeded.”

Since launching Simpl Global in 2018, Dibachi and his two partners, working out of Dibachi’s home in Lincoln and funding the project themselves, have reduced conventional solar batteries from shed-sized systems to portable, easy-to-install units as small and simple as a toaster. The battery, called the SimplBox, isn’t cheap. It runs about $1,000, and Dibachi says it will take the average home 10-15 of them to go “essentially off the grid.” He says he has sold several dozen of the boxes, which are manufactured in Reno.

As production is streamlined, that cost will decrease. “When we start selling them at quantity, economies of scale will kick in and bring the cost down and get energy storage to a place where it’s just another household appliance that people can install themselves,” he says.

Dibachi’s next goal is to make his batteries grid independent, so that a property owner’s solar panel system can directly power their building, even during a power outage. Most rooftop systems in use today are designed to work in sync with the local utility’s grid, meaning that if the utility’s power goes out, the building’s does too — even if there are batteries to store the solar electricity. But Dibachi has designed a new battery rigged with electrical hardware that allows the unit to send AC electricity directly into a home or business when the grid shuts down, making customers fully grid independent.

He has a prototype of this system completed. It’s called the SimplBackup, and Dibachi hopes to begin selling it midway through 2021.

As fossil fuels lose favor, Dibachi sees just one path forward: Solar power will generate more and more of our energy as our economies — homes, kitchens, buildings and cars — shift away from combustibles to clean electricity.

“That’s a change that’s upon us — it’s happening around us,” he says. “To complete that picture, you need energy storage. Cheap, easy, appliance-level energy storage really is the missing link.”

Hank: Making existing dumb HVAC systems much smarter

Buildings served by Hank, such as this one in Sacramento, have

seen 50-60 percent reductions in HVAC energy consumption,

according to Jerremy Spillman, the company’s chief revenue

officer. (Photo courtesy of Jackson Properties)

Managing energy use for precision efficiency is not a task that should be left to humans when there is an affable computer system capable of doing it.

Using artificial intelligence software, Hank — also the name of the McClellan Park company that created the system — overrides the standard programming of conventional heating, ventilation and air conditioning units. Ultimately, Hank claims to control temperatures inside buildings in a more even and efficient manner than most systems now in use, resulting in greater comfort and energy-cost savings for building owners.

Just as importantly, Hank improves existing HVAC systems without requiring new equipment, aside from a router. Often, a customer does no more than sign up for Hank’s cloud-based service.

“We don’t need any new equipment, and we’re not selling you any new hardware,” says Jerremy Spillman, the company’s chief revenue officer. “We’re taking your dumb equipment and making it smart by supercharging it with AI and advanced energy algorithms.”

Buildings served by Hank, Spillman says, have seen 50-60 percent reductions in HVAC energy consumption. That, he adds, translates into as much as 30 percent off the total electricity bill and with no comfort compromises. At the systemwide level, Hank’s technology, applied broadly, could alleviate the demand strains on the grid that can lead to rotating outages, like those during heatwaves that prompt millions to rev up the air conditioning.

Hank was launched in 2016 and in 2018 got a boost from a CalSEED grant of $150,000 to help the team prove its concept and create a product. In this period, Hank grew from a program that simply monitored a building’s HVAC system and periodically provided a report to the building’s owners on how to cut energy costs into an AI-driven program capable of managing the HVAC system.

Today, Hank services several dozen buildings totaling about 3 million square feet — and the sky’s the limit in terms of space to grow. Spillman says the built environment is responsible for 40 percent of the country’s carbon emissions.

“You put Hank in government buildings, in all these buildings that aren’t Energy Star-rated, and, all of a sudden, you don’t need to do a $500,000 controls project to make improvements,” he says. “We don’t sell you any new equipment — we just have a better, more efficient way to run your building, and all you have to do is sit back and let the AI do it.”

Spin Storage Systems: Making flywheel solar batteries to increase energy storage

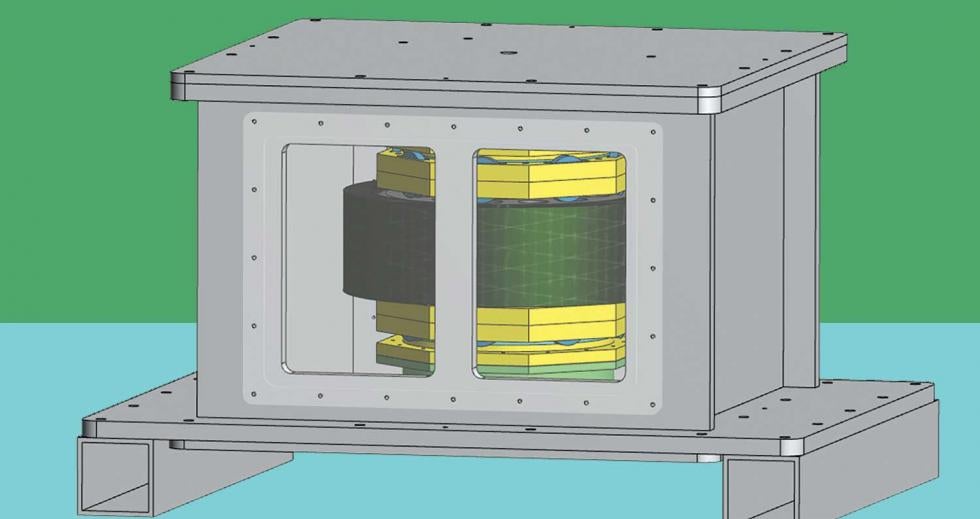

Spin Storage Systems is developing a prototype for an advanced

and low-cost flywheel battery in its tech lab in northwest

Sacramento. (3D drawing courtesy of Spin Storage Systems)

In a tech lab and machine shop in northwest Sacramento, a team of engineers is making wheels turn in phenomenal ways. The team is putting the finishing touches on a prototype for an advanced and low-cost flywheel battery — a spinning cylinder generated by solar electricity and, when the sun stops shining, keeps whirring away under the power of stored kinetic energy.

It’s not a new concept. Flywheels have been around for ages. Potter’s wheels, waterwheels and bicycles all utilize flywheel principles. Today, flywheels in the form of steel discs play a role in combustion engines.

But the Burlingame-based Spin, launched in 2011 and whose founder Jon Garber invented the QuickCam (a webcam video camera), is fine-tuning the basic components of its prototype to make a state-of-the-art flywheel solar battery that competes with conventional energy storage systems. The advantages of a flywheel system include no degradation of storage capacity over time, no toxic or flammable chemicals, and a lifespan of decades.

To charge any battery takes energy, and the customer gets to use that energy later at any time — but not all of it, because energy is lost in transmission. In these respects, a conventional battery offers an efficiency level of 80-something percent, explains Peter Cattaneo, Spin’s vice president of product marketing and business development.

Flywheels are better, but they still leak energy and will run out of juice if left uncharged. “A traditional flywheel might only spin for an hour or two after charging,” Cattaneo says. “We’re building one that will spin for days.”

Flywheels — even advanced models — also tend to grow unstable on their axis the faster they turn, costing energy and even posing dangers should the flywheel break apart. But Spin’s flywheel battery rotates on contactless magnetic bearings, and the whole system is kept in position, revolving around its natural inertial axis inside its case, with magnetic suspension, an improvement over flywheels that turn on ball bearings.

“We keep it positioned in the center of the case, because we don’t want it hitting anything, but we’re not forcing it onto any physical axis of rotation,” Cattaneo says. This means no air resistance, no contact between metal parts, minimal friction and a spinning flywheel that will hold kinetic energy much longer than existing systems. Spin has designed its flywheel with a 30-year design life, with no scheduled maintenance.

Spin, which has collaborated with Sacramento State University engineering students on multiple flywheel design projects, is still in its premarket prototype stage, but it’s getting close to releasing a product, which will look something like this: a 1-cubic-meter box weighing about 1,000 pounds containing a spinning hub that holds up to 30 kilowatt hours of electricity. Cattaneo says it probably won’t be much, if any cheaper, than conventional storage systems but will last much longer. “We’re going to sell you something that lasts 25 years at full capacity for the same price as a conventional battery that lasts 10 years and will only be at 70 percent of capacity by the end,” Cattaneo says.

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Promise for New Proteins

Advancements in the alternative-protein space ignite in the Sacramento area

In September, UC Davis was awarded the first federal funding

given to a university to research cultivated meat, positioning

the Capital Region to serve as a hub of the advancing

technology.

Vaccination Anticipation

UC Davis researchers join the global race for a COVID-19 vaccine

UC Davis is participating in a global clinical trial being run by Pfizer — one of the most promising vaccine trials to date.

Say Hello to Hope for the Upcoming Year

To open our December issue, Comstock’s executive editor looks forward to positive trends for 2021.

Startup of the Month: Unfold

Breeding seeds for vertical farms

The future of vertical farming begins on the genetic level. That’s the philosophy of Unfold, a Sacramento-based startup focused on innovating fruit and vegetable seeds to better serve indoor growing facilities.