Chris Hay wasn’t always such an ardent proponent of pasture-raised eggs.

“I was a vegan before I became a chicken farmer,” he says laughing.

Hay runs Say Hay farms, producing vegetables and tending to 1,600 pasture-raised, egg-laying hens on his 50-acre farm in Yolo County. His birds forage freely during the day, receive open access to soy-free organic feed and take shelter in mobile coops at night. By the end of the year, he hopes to add another 800 birds to his operation. You can buy a dozen of his eggs for anywhere between $8 and $12.

“I get it,” he says when I raise my eyebrows. “I couldn’t buy my own eggs. And that’s not because I’m trying to make a killing, it’s just what it costs to raise food humanely and ecologically.”

The Scoop on Pasture-Raised

Pasture-raised poultry is raised outside of confinement. While the birds have access to feed, organic or otherwise, they are free to roam in an outdoor environment, forage insects and grass, bathe in dust and exhibit other natural behaviors. And their eggs are pricey.

The implementation of California’s Proposition 2, which expanded space requirements for hens that produce eggs sold in California, has had ripple effects impacting producers, distributors and consumers throughout the nation. But as animal rights activists and demanding consumers realize the law hasn’t reflected their ideals, and as the price gap between commercial and specialty eggs narrows, will the elite pasture-raised egg enjoy a rise in popularity?

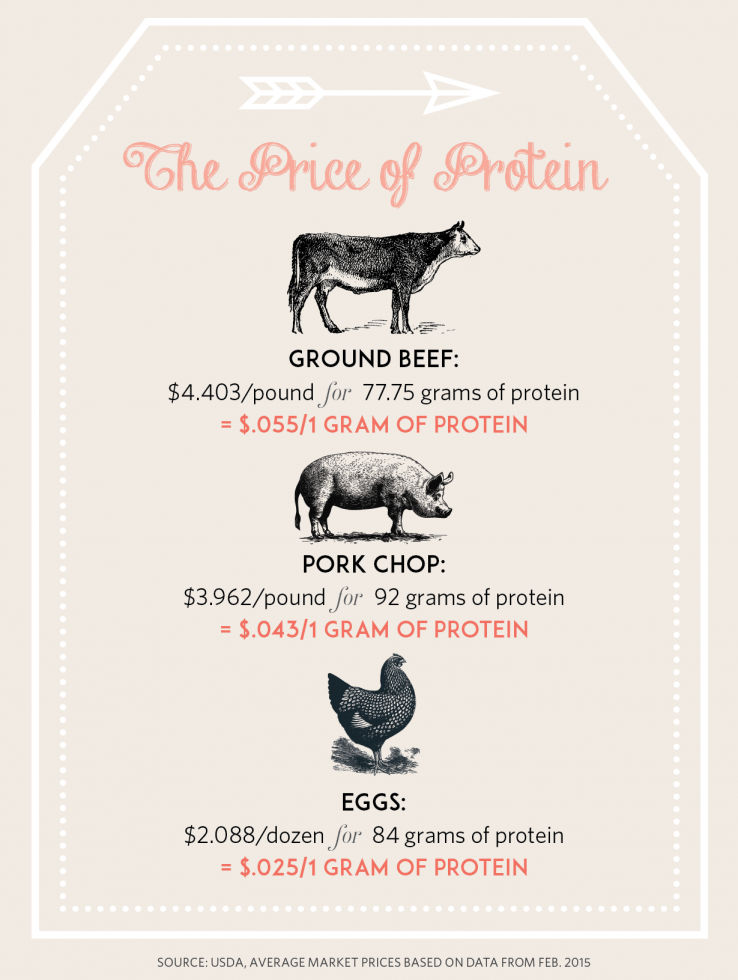

Prop. 2, which went into effect last January, requires that all egg-laying hens have the ability to fully extend their limbs, which has translated to only 116 square inches of cage space (about the size of a legal sheet of paper). That the average price of eggs — which are by far one of, if not the cheapest forms of protein — will rise as a result is undebatable. Ronald Fong, CEO and president of the California Grocers Association, told NPR last December that egg prices in California were increasing between 35 and 70 percent.

Hay isn’t convinced this will lead to greater demand for his own eggs. “I think for most people, if they have that moral compass, it’s already been tuned into the fact that what [industrialized egg production] is doing is not OK,” he says.

But Dan Brooks, the director of marketing and communications for Vital Farms (the only national pastured-egg distributor), sees the change as motivation for consumers to make the leap to his product.

“Cage-free eggs went up in price, free-range went up, but we kept our prices the same,” he says. “So the gap in price between our eggs and the rest was considerably narrowed. Where before it might have been a $1.50 jump (to pasture-raised eggs), now it’s closer to $1 or 75 cents. The financial jump consumers need to make is a lot smaller than it used to be.”

Brooks goes on to say that he’s seen a huge increase in demand at Vital Farms since 2009. The company, which is headquartered in Austin, Tex., launched in 2007 with only 50 hens. It now works with 60 farms, 14 of which are in California, and sells to almost 2,000 stores, 700 in this state.

“The market for pasture-raised eggs is growing rapidly,” Brooks continues. “It’s driven by consumers looking for a better quality egg and a farm existence that is reflective of their personal beliefs.”

Hay sells most of his eggs in the Bay area, where he says consumers are more apt to pay his asking price.

“No one is paying $8 for a dozen eggs in the Central Valley,” he says emphatically. “Maybe in Sacramento, but I think food in general is a weird thing. In rural areas, food is devalued even further because people see it all around them.”

Brian Boyce, the sales manager for Riverdog Farm (also in Yolo County), sees a similar phenomenon. All of Riverdog’s pastured eggs, at $8 a dozen, sell at farmers markets in Berkeley.

“There’s a very serious line that gets made by the people who show up, because we sell out at every market way before it’s over,” he says.

What’s in an Egg: The Mixed-Bag Market

Take a stroll past the eggs at your standard grocery store, and you’ll see a vast range in price and variety. And most of the marketing terms you’ll find on labels, pasture-raised included, have few-to-no regulatory guidelines.

Cage-free refers to hens raised in confinement but not in cages. Imagine an enclosed barn filled with a bunch of chickens — they are technically free to roam about, but the extent to which they can move depends on the size of the barn. Hens raised cage-free but in close quarters can see increased rates of hen-pecking and the rapid spread of disease. The standard 116-square-feet applies to floor space, though additional wall-mounted platforms can be added to technically increase overall floor space.

Free-range birds are raised in a barn but with access to the outdoors. According to the USDA, free-range producers “must demonstrate to the Agency that the poultry has been allowed access to the outside.” That access could be a gaping barn door leading into a half-acre of grass, dirt or gravel, or it could equate to an opening the size of a doggy-door leading to a 5-by-5 concrete patio.

“Cage-free, pastured or free-range — those are all marketing terms,” says Rex Dufour, who serves as the western regional office director for the National Center for Appropriate Technology. NCAT’s largest project is ATTRA, a sustainable agricultural information database funded by the USDA Rural Business Cooperative Services. “For example, a label saying free-range, the hens could have free range on a dirt lot with no green on it at all. You wouldn’t be lying, but there is nobody really regulating those labels. That’s why it’s important to know the grower, to understand how they do chicken-raising.”

Places like the Sacramento Natural Food Co-op set their own production standards that include a cage-free environment as well as the absence of unnatural practices such as forced molting. “We aim to provide information for our customers on how the food we carry is raised and produced and let them decide,” says Julia Thomas, the education assistant manager for the co-op. But she thinks there’s room for improvement. Thomas goes on to say, “We’re in the process of gathering more information about our egg producers and hope to visit some of their operations in the coming months. We may choose to discontinue eggs from producers who do not allow us to visit their facilities.”

“I couldn’t buy my own eggs. And that’s not because I’m trying to make a killing, it’s just what it costs to raise food humanely and ecologically.”

Chris Hay, owner, Say Hay Farms

Vital Farms also sets its own standards and requires 108-square-feet per bird, the same standard set by Certified Humane, a third-party certification body.

So, does a happier bird produce a better egg?

Consumers of pasture-raised eggs claim they have a richer taste and a sturdier, more robust yolk. Hay says a chef told him that she found herself using fewer eggs in her recipes when she switched to his product.

A 2010 study from Penn State University comparing the eggs of pastured and caged hens also identified a difference. While the eggs didn’t differ in weight, total fat, cholesterol or omega-6 fatty acids, the study found that pasture-raised eggs boasted higher concentrations of vitamins A and E and omega-3 fatty acids. Vitamin A concentrations were 40 percent higher, with concentrations double for vitamin E and omega-3 fatty acids. These numbers are reflective of similar studies out of the United Kingdom and Spain.

“It’s noticeable when you crack them open,” says Mike Badger, director of the American Pastured Poultry Producers Association. “You can see that they’re different. They’re upright and firm, not watery. The orange yolk is the forage component. And they have real taste.”

Setting the Price: Can Farmers Make it Work?

Even if the price gap between conventionally raised eggs and pasture-raised is narrowing, $7 for a dozen eggs can still feel like a lot of money to the average consumer. So why so pricey?

First, there’s the issue of size. Large, confinement operations can boast tens of thousands, even into the millions of hens (though many farms are decreasing the size of their flocks to accommodate the new regulations). Compare that to a pasture-raised farm, where flock size tends to cap out around 3,000.

After that, you have to factor in flock loss. Life isn’t always easy on the pasture, and pasture-raised hens can be easier for predators like hawks or coyotes to pick off. Pasture-raised hens also tend to have a longer lifespan (two to three years versus 9 months for confined hens), during which their lay-rate will decline by about 10 percent.

Chris Hay of Say Hay Farms gets his chickens from Vega Farms in

Davis. They arrive at his farm only hours old. Say Hay Farms eggs

are available at the Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op.

The labor costs are also higher than in confinement models. Moving and tending to mobile coops is neither quick nor easy.

“It might be less expensive to get started, but it requires more ongoing labor to make it work,” Badger says. “At the end of the day, it’s simply economics, and Prop. 2 in California is demonstrating how price can be affected by reducing the size of the flocks.”

In a 2011 study, “The Grass is Greener: Farmers’ Experiences with Pastured Poultry,” out of UC Santa Cruz, then-Ph.D. candidate Kathleen Hilimire found that half the pastured poultry farmers she surveyed reported a direct profit. That figure jumped to 78 percent when farmers were polled on the indirect profitability of their hens. Those benefits were increased customer interest and loyalty as well as higher soil quality, indicating that pasture-raised poultry are most profitable as part of an integrated farming system, which is the type of operation Hay runs.

“We use animals and vegetables in the same system and take the waste stream of one as a resource for the other,” he says. “So we use manure as fertilizer and use veggie scraps to increase the quality of feed.” For Hay, that’s the only way for humane flock-tending to be remotely profitable. But he says he finds that the soil created by his chickens’ foraging and fertilizing produces better crops.

“We notice with the crops we grow out here, not only are we applying little to no fertilizer, but they’re more resistant to pests,” Hay points out. “They’re more resilient, they last longer once they’ve been harvested, and the crops themselves are less prone to stress.”

But even considering the indirect benefits of producing pasture-raised eggs, Badger says their high price tag still comes down to basic economics.

“It’s not that pastured-egg farmers are trying to buy a vacation house,” he says. “They have to price according to their production costs.”

Hay estimates he operates with about a 20-percent profit margin for his eggs, which provide roughly 25 percent of his farm’s net profit. “It’s not easy, but a lot of us love what we do,” he says. “The trick is doing it for a living. Growing food is the easy thing we do, and growing food to make a living is one of the hardest businesses.”

Recommended For You

Legacy Crop

With J-E Paino at the helm, can Solano County lead the region to a rebirth of hops?

Paino has made a commitment to using all local ingredients in Ruhstaller’s brews, going so far as to grow his own hops yard. But it hasn’t been that easy. So what’s standing in the way of the Capital Region’s hops renaissance?

The New World of Ag

Investment in agtech is growing, but will the Central Valley cash in?

Through certain entrepreneurial eyes, agricultural technology looks a lot more relevant than the latest iPhone app or social networking tool. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, by 2050 the world will need 70 percent more food to feed an additional 2.3 billion people.. And the Central Valley is poised to cash in — if we play our cards right.

As the Bees Go

Local beekeepers prepare for another uncertain winter

Rick Schubert is settling in to the part of bee season that didn’t exist when he opened Bee Happy Apiary with 300 hives in 1977. It’s mid-September, and at headquarters, tucked in the dusty hills off a private road in Vacaville, the faint humming of honey bees serves as background buzz to the voices of men.

Of Rice and Men

On the Cover: Parched by years of drought, thousands of California’s rice fields lie barren

In the Sacramento Valley, where 97 percent of the state’s rice crop is grown, family farmers have been forced to fallow cropland they have worked for generations. The economic hit has been hard and true, affecting not just farmers, but seed distributors, equipment dealers and anyone else with a thumb in the rice business. The drought could cost Central Valley farmers and communities $1.7 billion this year and may lead to more than 14,500 layoffs.