Alvaro Ramirez, a lifelong entrepreneur who cut his teeth during the dotcom boom, recounts a story told to him by a small-scale strawberry farmer on the cusp of losing his farm. Unable to find an ideal buyer, the grower was selling his produce for half of what a distributor turned it around for.

“He didn’t have the network to sell it, to move or to market it,” Ramirez says.

So Ramirez set to work creating eHarvestHub, an online tool that connects growers to transportation and distributors at low cost. Farmers list their produce in a database, which retailers can then access. Once an order is made, eHarvestHub uses what Ramirez calls an “Uber model” to efficiently get product from the farms to the distributors.

“Fresh produce changes hands six to seven times before making it to the store,” Ramirez says. “I think tech can change that, bring things back to where they used to be when the grower picks it and brings it to the store. We can do that with technology.”

Through Ramirez’s eyes, agricultural technology looks a lot more relevant than the latest iPhone app or social networking tool. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, by 2050 the world will need 70 percent more food to feed an additional 2.3 billion people — so we’ll need to get innovative. And the Central Valley, with its rich farmland, ideal climate, access to ag research hub UC Davis and proximity to Silicon Valley capital, is poised to cash in — if we play our cards right.

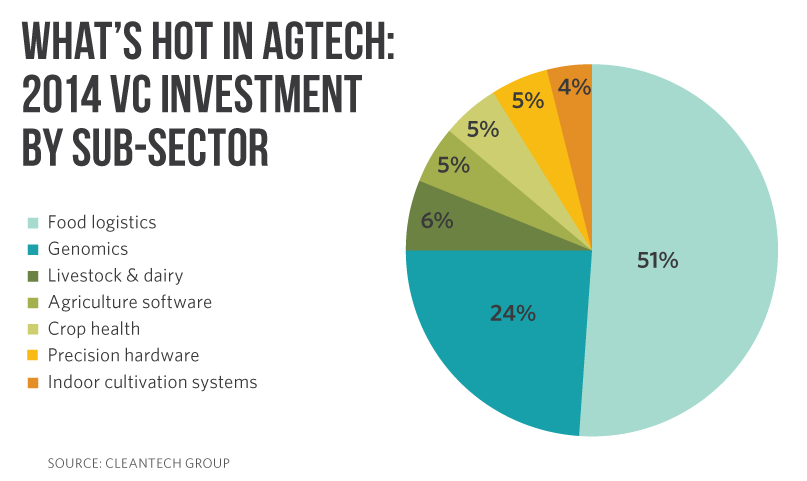

Investors, pay attention. According to CleanTech Group, which connects corporations with innovation via an online platform called i3, corporate and venture equity investment in the agriculture and food space increased 29 percent between the second and third quarters of 2014, with a total of $239 million invested — a 48 percent increase since the same time the previous year.

“I’d look at it as wants and needs; we all need to eat,” says Marty Reed, a partner with The Roda Group, an early-stage venture capital firm focused on clean technology. “The business opportunity is unquestionably there. If you can provide a better outcome for a grower, they will adopt. It make take some time, but they will adopt it.”

“Young farmers, they don’t want to farm the way their fathers farmed.” Rob Trice, founder, Better Food Ventures

Why Here?

The Kauffman Foundation’s 2014 report AgTech: Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Growth cites California as one of three areas in the nation where innovation in agricultural technology is on the rise. Given competition in the midwest and North Carolina, the Central Valley’s easy access to Silicon Valley is a huge asset.

But for Daniel Morash, a New Jersey native and founder of California Safe Soil, the region has more to offer than being part of a high-value neighborhood. A fertilizer developed by his company, based in West Sacramento, uses heat, mechanical action and enzymes to convert food to fertilizer in just three hours. Called Harvest to Harvest, the product can replace chemical fertilizers while increasing crop yields and reducing chemical runoff into groundwater. According to Morash, research facilities at UC Davis and easy access to state regulatory authorities in Sacramento made the Central Valley an ideal fit for the company.

“We’ve got a clean path to licensing and permitting and a natural transportation advantage over all other technologies,” he says.

The Central Valley has already seen significant investment from established companies. In 2013 Monsanto expanded its research facilities in Woodland, with $31 million put into a 90,000-square-foot addition. Last year, Bayer CropScience spent $80 million to grow research and development offices in West Sacramento. HM Claus, the fourth largest seed company in the world, has a headquarters and research facilities in Davis. And the region’s big agtech homegrown hero, biopesticide company Marrone Bio Innovations, netted a cool $56.4 million with its 2013 initial public offering. The following year a second round of financing drummed up another $40 million. (Bayer CropScience purchased AgraQuest, founded by Maronne, for $425 million in 2012.)

Rob Trice is the founder of Bay Area investment firm Better Food Ventures, which invested in eHarvestHub last year. He says that as younger farmers take control, opportunities in agtech will only grow.

“Younger farmers, they don’t want to farm the way their fathers farmed,” he says. “In Silicon Valley we’re seeing this low-cost disruption of information technology. I see no reason why that can’t be broadly applied and made accessible to more farmers.”

What’s Holding You Back?

Tech entrepreneurs venturing into agriculture aren’t always connected to their markets. (Ramirez spent seven months on the road interviewing farmers before feeling he had gained a sufficient understanding of how to serve them.) And though technology may be more approachable for younger farmers entering the industry, in 2012 the average age of a principal farmer was 58, according to a 2014 preliminary report by the Census of Agriculture. Add to that the fact that savvy investors are more used to WhatsApp-esque turnaround times on their investment, and you’ve got a landscape rife with opportunities for misunderstanding and faulty expectations.

According to John Selep, the founding and managing partner of the Davis-based AgTech Innovation Fund and board director for the Sacramento Angels, the business model in the web and mobile app space has been “polished and refined.” That’s not the case, he says, in the ag space. “It’s not as clear how to monetize user traffic and it takes a little longer for investors to become familiar with how the company works.

“The rate of success in IPO versus mergers and acquisition is very different in food and agriculture,” he says. “There’s still education needed to help investors build in some patience.”

And without substantial backing, it’s not easy for ag startups to develop and grow. The agricultural space hasn’t seen the same level of tech startup lifecycles that other industries have, and there are far fewer successful examples to learn from. Jack Coots, program manager for Sacramento Regional Technology Alliance’s AgStart track, says investors in the space aren’t the only ones in need of educating.

“Startup ag companies don’t have a lot of feet on the ground in the marketplace,” he says. “They have good ideas, but they haven’t been tested.”

“What we hear is that there is not yet a well-enough organized environment for innovation in this region. I think that’s where investing more in phyiscal and networking infrastructure will be helpful.” Josette Lewis, associate director, UC Davis World Food Center

For the Central Valley to solidify its position in agtech, Coots says, entrepreneurs need opportunities to connect with customers, float ideas, gauge interest and figure out what tweaks are necessary.

To that end, in April SARTA will host Field Days, the first of three quarterly meetups which will bring an entrepreneur’s product into the field to be demonstrated and then vetted by both investors and growers.

“It will allow the technologists and innovators to get immediate feedback from the marketplace and investors,” says Coots, “and investors can gauge the level of interest in the technology from the marketplace.”

Where Can We Put This?

If the Central Valley is to compete for global attention, it’s going to need more space.

“What we hear is that there is not yet a well-enough organized environment for innovation in this region,” says Josette Lewis, associate director of the UC Davis World Food Center. “I think that’s where investing more in physical and networking infrastructure will be helpful. There’s not a lot of prebuilt lab space.”

Matt Yancy, executive director of the Davis Chamber of Commerce, says the city is studying two innovation park proposals for a T-shaped set of parcels in Davis’ northwest area.

“There is a need for space for these agtech or biotech startup companies that are researching and developing these products to not only test their theories and determine if their product could be taken to scale, but to actually be able to take the company to scale,” Yancy says. “Here in Davis, given current land constraints, there just isn’t really a lot of room.”

Traditional business park management is focused on filling space and maintaining facilities. The Davis innovation parks will be governed by a combination of public, private and university voices with the intent of enabling companies to grow through connections to university research, business development and economic resources throughout the region.

“You’ve got a facility that has a vested interest in the success and growth of the companies that are housed within,” Yancy says.

Despite niches in need of filling, it would seem this is the Central Valley’s game to lose. SARTA’s first annual TechCon, held at the Sacramento Convention Center, saw standing room only at all four of its AgStart sessions. The World Food Center has brought TechCon panelists, including Trice, back to the region for brainstorming and networking. And Coots says SARTA is willing to go so far as to bus its partners up from Silicon Valley to attend Field Days.

“I’ve been working in the agtech space well over 10 years, and I’ve never felt as much momentum as I do now,” he says. “There’s a greater awareness of agtech and its opportunities, and the agricultural space itself is more open to seeing where technology fits into operations.”

Farmers are coming around as well, Coots says. “I had a grower tell me that it just needs to make ‘cents’ for him to embrace technology.”

Recommended For You

Startup of the Month: California Safe Soil

West Sac agtech company turns organic trash into fertile treasure

Daniel Morash doesn’t like to see spoiled food go to waste. In 2012, Morash and his brother, Dave, spent millions to launch California Safe Soil with one goal in mind: convert leftover organic material from supermarkets into a nutrient-rich soil amendment farmers could use to grow crops.

Status Check: Stevia First

It’s full speed ahead for this sweet startup

In 2013 we reported on Capital Region startup Stevia First and its CEO Robert Brooke’s goal of making his company the first domestic distributor of stevia. Stevia First made significant progress last year, most notably by entering into a partnership with China-based stevia distributor Qualipride International Ltd.

Touchscreen to Table

West Sacramento to address food access with Code for America

Code for America works with cities around the country, using open-source software to improve the scalability and reach of government services. Starting next year, Code for America fellows will work with the Sacramento Area Council of Governments and the city of West Sacramento using technology to tackle issues related to health care and food access in the city.

Comments

Here is an interesting article on the future of small organic farm operations in El Dorado County: "What nobody told me about small farming: I can’t make a living" - http://goo.gl/SUfSsE

hi I am an Broker working in hedge funds-commoditys and venture capital and I want to get into developing the new ag-tech future any advise is accepted gladly coming from an family farm achinery sales business originally I grew up with all the equipment best regards Patrick Jennings ceo pesgreen ltd