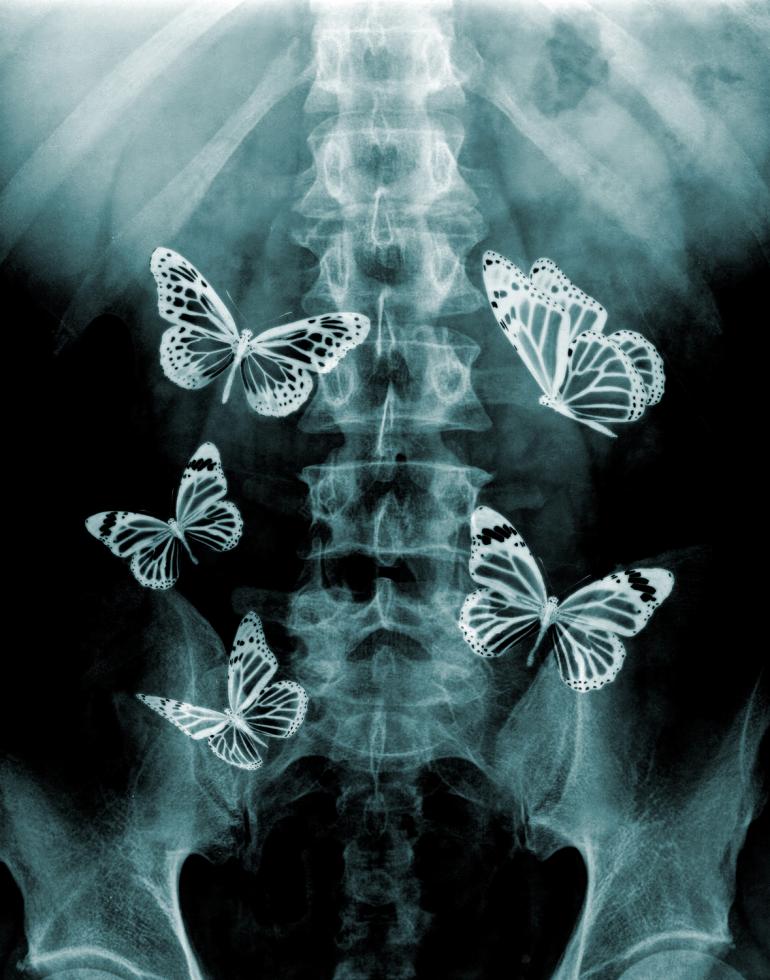

We’ve all been there: You’re waiting to give a big presentation, maybe you dread public speaking, and you feel your stomach twist itself into a pretzel. Or maybe you meet someone new, someone interesting, and when they make eye contact you feel your stomach do a joyful little flip. It happens all of the time. We feel things before we have time to mentally process.

Tired eyes? You can listen to the audio version of this article here:

But what if things like “butterflies in your stomach” are more than just cutesy cliches? Scientists are discovering that our guts are more complex and influential than we had fathomed. Our stomachs don’t merely send messages to our brain regarding hunger or digestion. The signals can have a fundamental impact on how we feel throughout our bodies. “Gut health is more important than most people think,” says Dr. Jason Guardino, a gastroenterologist at Kaiser Permanente South Sacramento Medical Center. “The bacteria in our gut have the ability to affect our body’s vitamin and mineral absorption, our hormone regulation, and it plays an important role in our immune response.”

It even plays a role in our mental health. Scientists are discovering new ways of understanding how the gut’s secrets can help us boost our mood, sharpen our memory and even live longer. (OK, it can also keep us regular.)

The Complexity of the Stomach

Gut health is an awkward thing to talk about. If you break your ankle, you can make jokes about your crutches, chat about the rehab and milk a bit of sympathy as friends sign your cast. But problems with your stomach? This invokes concepts like bloating, flatulence, constipation, diarrhea and “bloody stool.” The subject is taboo.

Video: UC Davis professor dives into the depths of human digestion

“Everybody knows about the heart and the lungs,” Guardino says. “They’re always in the news, and they’re the sexy topics.”

And yet the gut houses one of the most important clusters of nerves in our bodies. The enteric nervous system, often called the “second brain,” is threaded in the lining of our stomachs — so problems in our belly can lead to problems in our ENS. The ENS controls the gut independently from the brain, though it is in regular communication with our central nervous system. “The two nervous systems are very much intertwined,” Guardino says. “You can think of them almost like conjoined twins.” Remember those butterflies in your stomach I mentioned earlier? That’s the ENS revving you up.

The gut also pumps out serotonin, which can sway our mood. (In one of history’s gloomiest experiments, a 2014 study from Norway found a link between depression and stool bacteria.) “We used to compartmentalize things so much,” says Dr. Maxine L. Barish-Wreden, medical director of the Sutter Institute for Health & Healing in Sacramento. “We’d say, ‘There’s the brain, and there’s the nerves, and they’re each doing their own thing.’ But they’re all communicating with each other, all the time. When you disturb the system in one area, that affects everything. It’s like throwing a pebble in the pond.”

“It’s like a rainforest in your gut. It’s like outer space, but inner space. And we’re just starting to see the impact.” Dr. Maxine L. Barish-Wreden, medical director, Sutter Institute for Health and Healing

Perhaps this connection shouldn’t be too surprising. “If there’s something wrong in your gut or you’re not digesting your food well, of course it affects your mental state,” says Dr. Jonathan Eisen, a professor of evolution and ecology at UC Davis who has been studying the gut microbe for nearly 30 years. He speaks on a headset while riding his bicycle to campus, his voice calm and somehow not winded. “That all seems sort of obvious,” he says. “To me, what is more interesting is that we’re starting to understand how the gut has an impact on the rest of the body, and what the microbes are doing that might impact anxiety or affect the immune system’s development.”

A Rainforest of Bacteria

The gut is teeming with bacteria — billions of bacteria belonging to over 10,000 species in an ecosystem of staggering complexity. In 2007, the National Institute of Health launched the Human Microbiome Project, with a goal of analyzing, coding and classifying this labyrinth. (Think of the quest to map our DNA, but in our stomachs.) That study has revealed a vast ecosystem of genes, bacteria, viruses, yeast and parasites living together, and the harmony (or lack thereof) of this ecosystem has significant impacts on both our physical and mental health. “It’s like a rainforest in your gut,” says Barish-Wreden. “It’s like outer space, but inner space. And we’re just starting to see the impact.”

The gut, in a sense, functions as the barrier between the external world and our inner-selves. A weak barrier can make us physically or mentally weak. “When you have unhealthy patterns of bacteria, you’re more likely to have gut permeability, or ‘leaky gut,’” Barish-Wreden says. “When the gut barrier is not strong, then pathogenic bacteria in the gut are allowed to pass through the gut wall.” She likens this barrier to guardians at their post, keeping an eye out for intruders, dubbing everything from foods to external forces as either friend or foe. Because 70 percent of our immune cells are in or clustered near the gut, the gut impacts how well we combat diseases, stave off fatigue and absorb vitamins.

Ninety-five percent of your body’s serotonin lives in the gut. That feel-good matter then gets zapped from your gut to your head. We tend to think of the brain zapping signals to the rest of the body, but actually it’s a two-way street. So problems in the gut can cause problems in the mind, such as depression, anxiety and autism. “Recent evidence indicates that not only is our brain ‘aware’ of our gut microbes, but these bacteria can influence our perception of the world and alter our behavior. It is becoming clear that the influence of our microbiota reaches far beyond the gut to affect an aspect of our biology few would have predicted — our mind,” explain Stanford University’s Erica and Justin Sonnenburg in The Good Gut.

For an example of how the gut can impact our mental state, in a 2011 study of mice at McMaster University in Canada, a strain of “shy” mice were given the gut microbes of a more “aggressive” strain of mice, and once the rodents lived with their friskier counterparts’ gut microbes, then they, too, began to act more aggressive. Change the microbe, change the behavior. It’s easy to see how this could, potentially, lead to ground-breaking changes in how we think about food.

Related: The Robotic Stomach

Eisen’s team at UC Davis examines the ecology of gut microbes, using the same analogy as Barish-Wreden. “It’s similar to how people would study a natural rainforest,” he says. Where does each gut microbe come from? How do these millions of microbes relate to each other? Can they be mapped? How do they change over time? “Just like you look at how a volcano is born from an island, we try and look at where the gut microbes come from,” he says.

Scientists are now analyzing the fecal matter of babies, then seeing how that changes over time — while breastfeeding, at 2 years old, then at 4 years old, etc. When Eisen began his research in 1989, it took him a year and a half to sequence 1,500 “bases” of gut DNA. But now, thanks to faster computers and miniature robotics that can create “test tubes the size of your thumbnail,” his team can now sequence a billion bases in less than a day. He hopes this research will eventually give us clearer answers to question like: Could antibiotics be causing more problems than we realize? Do they wreak havoc on our gut’s ecosystem (and thus flummox the ENS and our brain-axis), just like how, say, carbon dioxide could change our environment?

So far there are more questions than answers. But while this precise mapping of the gut’s microbe is a new phenomena, Barish-Wreden says we’ve seen the clues for decades. As far back as 1908, a Russian scientist by the name of Ilya Mechnikov found that people in Bulgaria lived longer than in other countries, and their diets had one key thing in common: They were high in fermented milk products, like yogurt. He was one of the first to cite the benefits of “good bacteria” in our guts, and he has been called “the father of probiotics.”

Speaking of …

Probiotics and the Brain

At the most basic level, scientists have found that some bacteria are good for us, some bad. A condition called dysbiosis occurs “when we have too many ‘bad bugs’ that have overtaken the ‘good bugs,’” Guardino, of Kaiser, explains. Dysbiosis can trigger not just the expected symptoms like inflammatory bowel disease, but also seemingly unrelated conditions like acne, anxiety and multiple sclerosis.

Related: Jason Guardino on How Our Gut Matters

If you follow the “second brain” to its logical conclusion, then you might wonder: Should we take supplements for our gut? If the gut can influence our moods and even change the workings of our brain, why not give it a boost? Enter the world of probiotics, a live bacteria yeast that stimulates the growth of microorganisms, especially those with beneficial properties.

It’s true that probiotics are very real and our gut needs them for proper digestion. The experts I spoke to all agreed that they might recommend probiotics in a short-term burst to help with a temporary illness, such as irritable bowel syndrome, which Guardino describes as “the No. 1 diagnosis that GI doctors make, by far.” Yet, they would generally not recommend using probiotics as a long-term solution, or in the hope they will be a panacea, or a way to combat depression or sharpen our memory.

“If we’re eating healthy food, such as good vegetables, good fiber and good fermented food, then we don’t need the additional probiotics,” says Dr. Rana Khan, the department chair of gastroenterology for Dignity’s Mercy Medical Group. He doesn’t personally use them, instead opting for regular snacks of yogurt, which, like most fermented foods, are packed with good bacteria.

Barish-Wreden also cautions that too many probiotics could disrupt that natural environment. They can be thought of the digestive version of “mono-cropping.” With over-the-counter probiotics, “you’re taking the same strain over and over again — the same crop — and feeding it to your gut,” she says. “This might not create the conditions to let your gut do what it needs to do, which is creating its own rainforest,” says Barish-Wreden.

Gut Check

Instead of leveraging probiotics as a way to enhance that second brain, the more straightforward approach is to simply eat gut-friendly food. The best choices? “What’s good for your heart is good for your gut,” says Guardino. He tells his patients to avoid anything that comes from a bag, a can or a box and promotes a mostly-plant-based diet.

A variety of food is key. Different fruit has different fibers and antioxidant properties. Khan offers bananas as an example: If someone eats a banana every day as their only source of fruit, sooner or later they will feel more bloated. He recommends mixing in things like apples and mangoes. The pace of consumption also matters. “Chew your food really well,” he says. “Enjoy your meal. Think of it as your last meal. Make it thin and liquidy before you swallow.” This also helps you eat less. He learned this not in med school, but from his grandmother; when he was a kid he would shovel food in his mouth and says his grandmother would throw her shoes at him and say Slow down! (“That’s why I’m a digestive specialist,” he adds, laughing.)

If this strategy sounds decidedly low-tech, or even primitive, well maybe that makes a certain sort of sense. The power of the gut is not new. It has taken recent technological breakthroughs to help quantify, classify and categorize the billions of gut bacteria, but at least one doctor has been well ahead of the curve. Over 2,000 years ago, Hippocrates, told us that “All disease begins in the gut.”