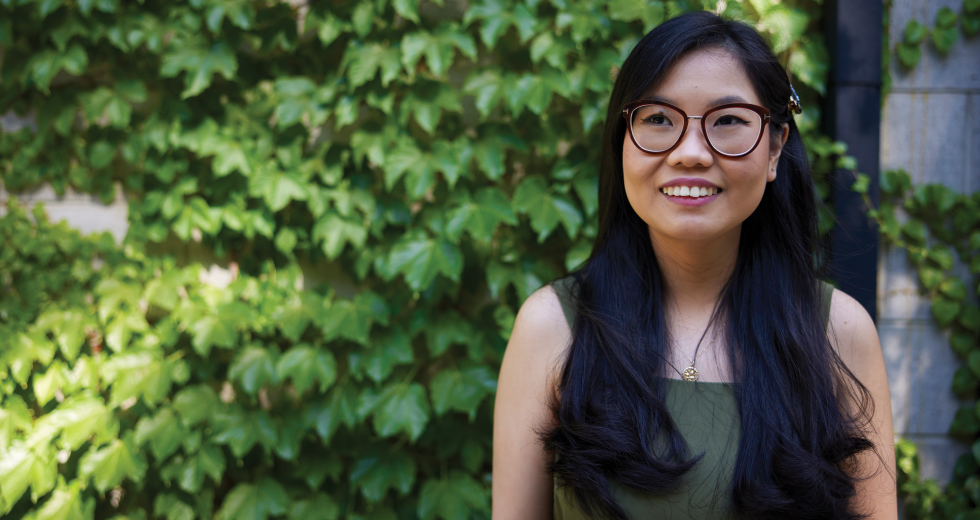

Tinn Salinas is a UI/UX designer. In 2013, her family migrated from the Philippines to Sacramento and she tried to get a design job. She felt confusion and culture shock. “I developed self-doubt,” she says, and struggled to navigate the job market as a 20-year-old (which is a tall order for anyone). “I started questioning myself. What’s wrong with me? Is it the language barrier? Is it the skills?” She and her family soon moved back to the Philippines, where she eventually landed a job at a design firm called Wide-Out Workforces, Inc.

In 2019 she moved back to the Capital Region. Still at WideOut, she focused on designs for VSP, its Sacramento-based client. Salinas did well and moved up the ranks. Soon she managed a team of 12 designers that knocked out 2,000 design projects per quarter, such as brochures and billboards. But she felt lingering doubts about her portfolio, her writing and her overall performance. “I just felt that I wasn’t doing well enough, or that I wasn’t going to cut it,” says Salinas. She still felt adrift in the job market, unsure how to hunt for a higher paying job.

Then a coworker shared an Instagram post about a program called Ascenders Academy, a nine-month mentoring program from Capitol Creative Alliance. Salinas immediately signed up to be in the first cohort, pleasantly surprised that it was free. So did dozens of other mentees and mentors who were organized into pairs. Throughout the Capital Region, formal (such as the UC Davis Group Mentoring Program) and informal (impromptu coffee sessions) mentorship is on the rise.

“Mentorship is more accepted now. If you look at what mentorship is, it’s really about asking for help. Ten or 20 years ago, that was seen as a weakness.”

Marcy Wacker, Program director, Ascenders Academy

“Mentorship is more accepted now,” says Marcy Wacker, design workforce lead and program co-lead of the Ascenders Academy. “If you look at what mentorship is, it’s really about asking for help. Ten or 20 years ago, that was seen as a weakness.” Wacker says now mentorship is seen as empowering — a way of “advocating for yourself.”

As more and more local executives are discovering, mentorship helps the mentee, the mentor and the greater Sacramento economy.

Opening doors

Jane Einhorn, former partner with RSE, formerly known as Runyon Saltzman advertising agency, who is now the owner of JE Public Relations, has been mentoring young professionals in Sacramento since the 1980s. She sees this as a way to pay it forward, and happily answers calls from anyone who seeks her advice. “I had a very good mentor,” says Einhorn, referring to the late Jean Runyon, the legendary founder of RSE. “I probably wouldn’t have had a career this successful if it wasn’t for Jean. She taught me how to meet people, have a sense of humor and get new accounts.” The questions Einhorn’s mentees tend to ask: How do you get a job? How did you get to be successful? Sometimes they ask her, “How did you do it when you had two kids?”

Lydia Ramirez, senior vice president at Five Star Bank, estimates she has mentored well over 100 young professionals, “mostly up-and-coming Latinas.” Ramirez says since she’s the highest ranking Latina in banking in the Sacramento area, people often ask her, “How did you do it? How did you make the C-suite?”

Sometimes mentees are looking for a job. Sometimes they need help with their portfolios. Maybe they’re confused on how to navigate the rocky waters of freelancing — increasingly important in our gig economy. Or maybe this is their introduction to networking. “For a lot of mentees,” says Wacker, “it’s easier to do a one-on-one thing as an entry point to meeting more people.” And sometimes a mentor can add value by showing that a profession is not a good fit. “They may decide that PR and advertising is not for them, so you’re doing them a favor,” says Einhorn, who has seen mentees leave the field and become lawyers.

What does mentoring look like, exactly? “Maybe it’s a phone call before they go into an interview, to give them confidence,” says Lydia Ramirez, senior vice president at Five Star Bank.

What does mentoring look like, exactly? For Einhorn, pre-COVID-19, it often meant a monthly meeting at Peet’s Coffee in Sacramento neighborhood Sierra Oaks. The Ascenders Academy used regular Zoom meetings. “Maybe it’s a phone call before they go into an interview, to give them confidence,” says Ramirez, adding that it can also mean reviewing a resume or opening up her Rolodex. “Driving information and driving inspiration,” says Ramirez. “That’s what mentorship boils down to.”

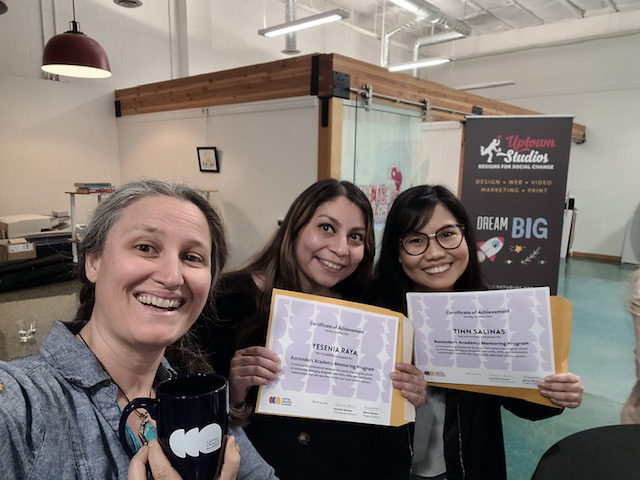

Heather Hogan mentored Tinn Salinas through the Ascenders

Academy, which pairs mentors and mentees.

Salinas took the homework seriously. At Hogan’s suggestion, she made tiny tweaks like changing “Digital Designer” to “UI/UX Designer.” This sounds minor, but Hogan’s experience in the field taught her that this is more likely to catch the eye of an employer. Salinas redesigned her website. She had anxiety about her writing, so Hogan suggested that she start a blog to gain confidence and showcase her chops. Salinas began writing posts with smart UI commentary, such as how, if she worked at Google, she would improve the interface of Google Chat.

They also talked about substantive work challenges. One of Salinas’ sharpest pain points was the amount of turnover on her design team, which wasted too much time on training and onboarding. After picking Hogan’s brain, Salinas created an internal playbook for new designers who worked on the VSP account, providing a turnkey solution for training and onboarding. This had an immediate impact. Soon the team spent less time on training and more time designing, expanded from 12 designers to 21, and cranked out more projects, boosting revenue for the group. The playbook worked so well, they’re now planning on adapting it for other clients.

“I really treasured the time the mentor spent with me,” Salinas says. “She gave me a lot of resources and helped me with my current job.” When the nine months of Ascenders Academy concluded, Salinas (who’s still at WideOut) proudly created a slideshow that showed what she had learned, then presented it in person at the end-of-year party.

This was only possible because Hogan made herself available, and that’s a hallmark of a good mentor. “No matter how busy you are, you have to make the time,” says Ramirez, who squeezes in calls whenever she can. Other qualities of a good mentor: willingness to share their experience and connections (as opposed to hoarding contacts), a genuine interest in helping others and a knack for candor. “One thing I encourage is for mentors to be frank about their own experiences,” says Wacker, who adds that design is often seen as a glamorous profession, but a good mentor can paint a more realistic picture of the inevitable bumps and trapdoors.

And a good mentor has the patience to deal with scheduling mix-ups, panicked phone calls or rookie mistakes from the mentees. Wacker found at Ascenders Academy, the biggest challenge was keeping the pairs connected. “I will be honest … that was 100 percent on the mentee side,” says Wacker. “I’m trying to impress on the mentees, without being too heavy-handed, that these folks are professionals and they’re taking their time for you.” For Einhorn, the biggest challenge of mentorship is when “people don’t listen to me.”

Do you want to become a mentor but you’re not sure where to start? Official programs like Leadership Sacramento or Ascenders Academy are obvious onramps, but often it just sort of happens. When Hogan was teaching a design class at Sacramento City College, one of her students invited her to lunch. “I was confused,” Hogan says with a laugh. “Like, are we friends?” And then at the end of the lunch the student said, “Now I have a mentor!” Hogan and the student stayed in touch and frequently discussed her career path, “and now she’s making six figures.”

Hogan also endorses what she calls “peer mentoring.” She organized a group of six artists called the Creative Mastermind Group that meets every two weeks. This is more structured than the occasional coffee. Their sessions alternate between group critique and the “hot seat hive mind” where members gently but constructively critique each other’s work and then help one another tackle specific problems with clients or careers. “I hope you encourage people to start their own group,” says Hogan. “It’s not that hard!”

The surprising mentoring ROI

In one sense, mentoring is an act of volunteering that’s chicken soup for the cubicle soul. It’s selfless. “I’m still kind of verklempt by how willing these established professionals were to give back to their creative communities,” says Wacker. “They don’t really have any reason to do this.” But in another sense, even if this is not their motivation, mentors often do benefit from the relationship in surprising ways.

“It’s good for business,” says Einhorn, who has found that over the course of her long career, sometimes mentees can get new jobs, move up the ranks and later become clients. (One of her mentees from RSE is now an executive at a bank and pays her for public relations work.) “It helps build connections and collaborations” for both the mentors and mentees, says Hogan, “because we all know people don’t get jobs because of your resume; you get it because of who you know.”

Mentoring can also be a way to sharpen leadership skills, something that even the most successful freelancers rarely get a chance to do. “In graphic design, there’s not a lot of opportunity for leadership roles,” says Wacker. “This was a real opportunity for these mentors to grow their own skills, which might have been a little dormant.”

Tinn Salinas (far right) says she received helpful resources from

her mentor. She also focused on enrichment by spending nine

months with the Ascenders Academy.

Mentorship can even help the region. It’s a way to cultivate and retain talent. Years ago, “Sacramento was never a hotbed of advertising and public relations,” says Einhorn, but thanks in part to a culture of mentorship, “People don’t have to go to San Francisco to get a job at an agency. The creative community has become quite sophisticated.” This is one of the reasons Wacker helped launch Ascenders Academy. “We really need to foster and grow and develop this amazing talent pool that we have in Sacramento,” says Wacker. “I see that as part of our mission.”

While mentoring is no silver bullet, it could be a way to improve issues of equity. “Coming from a place of generational white privilege, I’m always amazed at what I learn from people who aren’t like me,” says Hogan. “And I’m always trying to find ways to meet more people who aren’t like me.” She knows that first-generation college students or young professionals migrating from other countries (like Tinn Salinas) can have a hard time navigating the corporate landscape, and that “it’s really important to bring more people in.”

This is especially true in finance, says Ramirez, as banking “has always been a ridiculously conservative industry.” When young professionals are starting out, says Ramirez, “they don’t see a lot of high-ranking C-suite individuals who are either Latina or Latino. They don’t see them. And for me, representation matters.” If Ramirez can be an inspiration, then she considers it “my duty to make sure I do what I can to bring them up with me.”

Ultimately, says Ramirez, she’s trying to break down barriers. And mentorship is a way to do this, because “sometimes it takes just one person to make it possible.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Women in Leadership: Lydia Ramirez

Our annual salute to extraordinary women who are shaping our future

Lydia Ramirez, senior vice president and chief operations officer at Five Star Bank, is the Sacramento region’s highest-ranking Latina in the banking field.

A Good Mentor Is Hard To Find

Women need mentors, but the search for one isn’t always easy

Sarah Sciandri is looking for a woman, but finding one is tougher than she thought. The 34-year-old likes her job as a marketing manager for the Sacramento architecture firm Nacht & Lewis, but she wants a female mentor to help move her career forward.

Young People Are Our Future Community Leaders

Younger generations are rising to leadership positions as older people edge out of the workforce. To introduce the 2022 Young Professionals issue, Comstock’s president and publisher reflects on what makes these generations unique, and perhaps more importantly, what they have in common.

Closing the Power Gap

Black Star Fund CEO and Chairman Kwame Anku on the importance of investing in Black entrepreneurs

Comstock’s spoke to Anku about his fund (which plans to close at $12 million in May) and the importance of investing in Black entrepreneurs.

Making a Dream Team

How to become a leader who wins hearts to maximize performance

These three steps can improve your leadership capabilities and help create the dream team that you have always wanted.