The narrative of Andrew Susac’s 2014 season did more than just further his promising baseball career. The Roseville native’s sudden ascent in late July from minor leaguer to eventual World Series champion opened up a breadth of new financial opportunities, too. His salary jumped from $1,600 a month to $3,000 a game, he earned a full World Series share of more than $380,000 and became vested in Major League Baseball’s lucrative pension plan, putting Susac on a path toward a financial future afforded to only a tiny percentage of 24-year-olds.

How does a young, talented player like Susac handle the complexities of this new opportunity, ensuring his financial health while staying focused on the athletic skills that allow him to compete on his profession’s biggest stage? That’s a question every big-time athlete has faced, especially in the era of free-agency and multiyear contracts that can reach into the hundreds of millions.

Though the road to the major leagues was sometimes bumpy for the 2009 Jesuit alum, Susac spent barely 90 days with the San Francisco Giants before his childhood dream of playing for his favorite team in a World Series became a reality.

Now back in Roseville for the off-season, Susac is staying at his parents’ home with his fiancé, Maggie Doremus, until spring training begins in early February. During a post-Series Hawaiian vacation in late October, Susac proposed to Doremus, a softball player he met his freshman year at Oregon State. They are planning their wedding for this coming November.

To successfully navigate his fledgling career, Susac relies on the advisors who have supported his goals from the day he signed his first contract: family members, an agency that handles contract negotiations and marketing, and a group of financial experts who help him manage his income and investments.

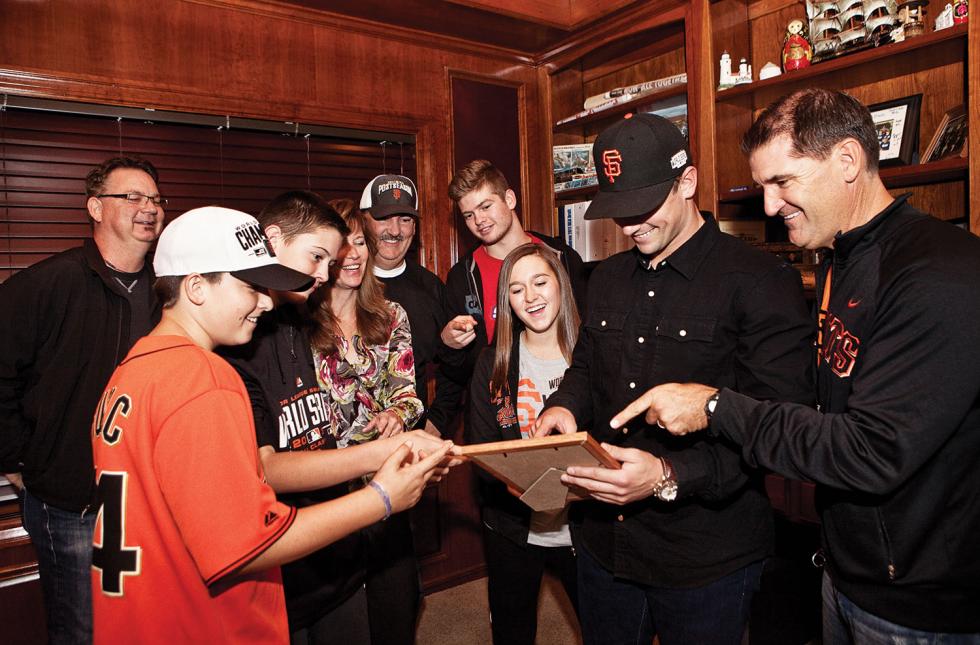

Andrew Susac’s family provides more than moral support. His

uncle, John Susac, to his left, counsels him on financial matters

as well.

Those family members, especially Susac’s “two dads” — biological father Nick, an area builder; and Nick’s brother John, owner of several small businesses, are there for him day in and day out.

There are a few simple messages advisors want Susac to learn early: control spending, don’t dip into the $1.1 million bonus you’ve already earned, and plan as if your career will end tomorrow.

“That’s where we (players) can get sidetracked, thinking money will grow on trees,” says Susac, who uses a single American Express credit card during the season so that every expenditure is tracked. “People don’t realize that we only work six months of the year, so that’s six months we receive no income. We’ve been looking at this like my signing bonus is what I’m going to live off my whole life.”

The financial life of a professional athlete is complicated. For example, a player must pay income taxes in several, but not all, states he plays in, and daily cash exchanges like meal money on the road and fees for clubhouse personnel are subject to taxes. But Susac says he’s always taken an active role in his finances, and is learning more all the time.

Susac has looked out for himself financially, “going back to college when I was living off a $500-a-month stipend,” he says. He enjoys monitoring his investments and talks regularly with his financial advisors. “I won’t say I’m the smartest about it, but I know how it works. The best way to look at this is to play (the game) like you’ll never play again, and to live like you’ll need the money you’re making now the rest of your life.”

Susac hasn’t spent extravagantly since his promotion to the major leagues. He drives a used BMW he bought for under $20,000 after having sold a truck for about the same price.He often drives his fiance’s SUV around Sacramento.

Jonathan Endo is an associate at RGT Capital Management, the firm that has handled Susac’s finances since he signed with the Giants in 2011. Endo says the firm’s goal is to empower its clients to manage current income so that it will last long after a career has ended. The firm also monitors clients’ risk management and manages estate planning.

John Susac says the strategy involves investing 75 percent in stocks and 25 percent in tax-free bonds, with no investments in real estate. Stocks are split between aggressive small cap and large cap dividend.

Endo says there are four lifestyle phases to a baseball player’s career that must be managed: reaching the majors, arbitration or the first big contract, mid-career, and end-of-career and beyond.

“The majority of professional athletes will make most of their money in their lifetime when they’re young, so they have to make it last,” Endo says. “We always say that you can’t control the stock market or interest rates, but you can control your spending.”

An athlete’s career is tough to navigate. You might be traded. A major injury can doom your career before the real money starts flowing. Even signing a big contract — the average MLB player makes about $3.5 million per year — doesn’t guarantee fiscal solvency, as bankruptcy has claimed even those who have made hundreds of millions of dollars during their careers. A Sports Illustrated article in 2012 reported that 78 percent of players in the NFL and 60 percent in the NBA face bankruptcy or serious financial stress within just a few years of leaving the game.

“I remember getting that first paycheck and seeing that big number. I’m sitting at my locker next to Buster Posey, and Buster is going, ‘You’re in the big leagues now.’ Andrew Susac

Matt Walbeck, a 1987 graduate of Sacramento High School who has experienced the ups and downs of a professional athlete’s life, has been a mentor to Susac since high school. Walbeck, a catcher who originally signed for $20,000, played more than six years in the minors before embarking on a decade-long career with six major league teams from 1993 to 2003. After he stopped playing, Walbeck worked as a minor league coach and manager before quitting the pro game for good in 2011. He now operates the Walbeck Baseball Academy in Folsom.

“When you reach the majors, you tend to have a lot of cash in hand because of things like meal money when you’re on the road (about $100 a day in 2014), so it’s easy to get into bad spending habits,” Walbeck says. Early in his career, Walbeck connected with a financial advisor, Mark Gillam of Fair Oaks, whom he still works with today.

“You get sucked into the lifestyle, then when you’re out of the game and you’re making zero dollars, there’s more money going out than coming in,” Walbeck says. “That’s a problem.”

Walbeck says the people pushing investments and get-rich schemes to pro athletes are a constant, and the rock star lifestyle can lead to “some pretty poor decisions.” He remembers players who, flush with cash, would charter their own planes to get to games.

When Susac’s milestone 2014 season began he was a minor leaguer navigating his way through his first season with the Triple A Fresno Grizzlies. A second-round draft choice out of Oregon State University in 2011, Susac signed a $1.1 million bonus and then steadily rose through San Francisco’s farm system.

The Grizzlies played two series at Raley Field in West Sacramento in April and June, and in front of dozens of friends and family, Susac slugged a home run during each trip. In July, Susac was selected to play in the Pacific Coast League All-Star game held in Durham, N.C.

Then came Friday, July 25. San Francisco’s backup catcher Hector Sanchez suffered a concussion that would sideline him for the rest of the season. That night, Susac, on a road trip in El Paso, got the call from the Giants.

Just before midnight, Andrew reached his father, Nick, who, along with his mom, Shawnna, a brother and numerous cousins, were camping near Lake Tahoe.

“Pack your bags,” Andrew said. “We’re going to San Francisco.”

Andrew Susac’s rapid rise to the majors changed his athletic and

financial fortunes

Shawnna, a patient advocate at Mercy Medical Group, recognized a delicious irony in the moment. “And to think we were on our first nonbaseball vacation in years,” she says.

The family rolled into San Francisco in time to catch Saturday night’s game against the Dodgers and watch as Andrew got his first big league at-bat. (The Giants, per Susac’s contract, put the extended family up for the week, supplying tickets and lodging.)

Over the next three months, Susac, considered one of the best young catching prospects in baseball, emerged as a key component of the playoff-bound team. His high level of play earned him one of the 47 full World Series shares of $388,605, which were voted on by core team members from a total pool of more than $22 million.

Susac says the entire experience has yet to sink in. “I wasn’t expecting to get to the major leagues that fast, and to think that I’m a World Series champion, that I’ll get a ring after my first year, is just really crazy.”

Once promoted from Triple A on July 26, Susac began earning a salary at the major league minimum of $500,000 per year. The minimum goes up to $507,500 next year, according to his agent Brodie Scoffield of Legacy Sports Group. Scoffield notes that Susac, technically still a rookie, would be subject to a salary set by the team until 2017, the year he would first be eligible for an arbitration hearing.

The team could at any time also offer Susac a multiyear deal, which happened with starting catcher Buster Posey, who signed an 8-year, $167 million contract before his fourth year with the Giants after winning the league’s Most Valuable Player award.

Though Susac is still a long way from a Posey-like contract, even the major league minimum salary was an eye-opener.

“I remember getting that first paycheck and seeing that big number,” Susac says. “I’m sitting at my locker next to Buster Posey, and Buster is going, ‘You’re in the big leagues now.’”

Susac’s two months of service in San Francisco earned him about $200,000, after making $8,500 during his three months in Fresno. His World Series share almost doubled his regular-season earnings.

Additionally, Susac has qualified for the MLB pension, which includes health care and is considered the best in professional sports. There are three tiers of investment options, but MLB players must only play 43 days in the majors to earn a minimum annual plan of about $34,000. After 10 years in the big leagues, benefits can total $200,000 annually if taken at age 62.

Pitchers and catchers report to spring training in early February, and for the first time, Susac will head to camp as an experienced major leaguer. His family will be there to support him, as they have the past three years, and he is confident they will be with him long after his career comes to an end.

Editor’s Note: In the original draft of this story, we incorrectly stated that Susac was no longer a rookie. Paragraph 30 has been edited for accuracy.

Recommended For You

The New Team in Town

River Cats become Giants' Triple-A affiliate

The Sacramento River Cats, for 15 years regarded as one of baseball’s most successful minor league organizations, announced in September it would be making a big switch. Beginning this season, the team will no longer be the Triple-A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics but will instead become the top-dog minor league team for the San Francisco Giants.

Create the Future. Now.

The Sacramento Kings' Ryan Montoya scouts the globe for the best in tech

Ryan Montoya’s task is clear, straightforward and possibly, well, impossible: Turn the Sacramento Kings into the most technologically adept sports franchise in the world.

Status Check: Roseville Sports Complex

Placer Valley Tourism makes progress in large-scale sports development

Last May we reported on the upcoming development of a $30 million, 12-field soccer complex in west Roseville and the addition of five baseball and softball fields in the existing Whitney Park complex in Rocklin. Here’s where things stand:

Comments

I knew you were a keeper from the first time I saw you catch! You also have great taste in dogs! What is your Vizla's name?

Ellen, his dog's name is Wrigley. And even though Andrew Susac hit his first major league home run at Wrigley Field last August, the dog had been named several months before, ironically.

Pitchers and catchers report to spring training in early February, and for the first time, Susac will head to camp as an experienced major leaguer. His family will be there to support him, as they have the past three years, and he is confident they will be with him long after his career comes to an end.