January and February 2015 were dark times for Chris Benziger. He was the youngest of five brothers in the family business — the Benziger Family Winery north of Sonoma — and assumed he’d work there the rest of his life.

Benziger’s father Bruno and oldest brother Mike started the vineyard in 1980. By nine years in, sales had grown from 10,000 cases a year to more than 3 million. From a company run only by family members, it grew to 150 or so employees. The brothers were on the same page: Every quarter for ten years or so they’d been holding “blue sky” meetings to plan for the company’s future leadership and discuss business ideas.

But the Great Recession of 2008 crunched the industry, forcing

consolidation and squeezing small wineries on price. Mike got

cancer, and other brothers were nearing retirement age. In the

changing business climate, the older brothers were uncertain

whether the company had the leadership to survive. So early in

2015 the officers — the five brothers, a brother-in-law and two

others — had a discussion on whether to sell, and a majority said

yes. Only Chris Benziger and another

partner said no.

“It was devastating for me personally because not only was it ‘you’re losing your whole life,’ but also it’s like, ‘What, you guys don’t trust me?’” he says. “And also like, oh, we are no different than the Mondavis, we’re no different than the Sebastianis and all those winery squabbles you hear about. Like, we are better than that.”

It turned out they were. All that open communication in those quarterly meetings helped them be clear about the outcome they wanted in a sale. After doing a dozen interviews, the company found a buyer — The Wine Group, one of the world’s largest wine companies — that committed as part of the purchase to keeping the company intact, including all its employees and managers, and continuing its green farming practices. The Benziger Family Winery is one of its brands, and Chris Benziger stayed on as brand ambassador.

Most importantly, though Chris Benziger opposed the sale, he still has a solid relationship with his brothers. There were no lawsuits. “I didn’t lose my family. I still love my family. I still hang out with all my brothers,” says Benziger. “And that’s probably the biggest thing — it would be a real tragedy to not just lose the business, but also lose the people.”

There’s been no systematic study of the links between firm failure and family feuds, but some business experts think the connection is obvious. Kurt Glassman is a founding partner at Sacramento-based LeadershipOne, one of whose specialties is helping family businesses with conflict. In his experience, more than half the time failures can be traced back to the family’s inability to get along, he says. A 2007 study of 60 family firms in the Journal of Business Venturing concluded that “family firms plagued by conflict suffer from performance problems.”

So managing family business conflict isn’t just about harmony but survival. There’s nothing wrong with disagreements — managed well, they ensure diverse perspectives that are good for a business’s mission and sales, say experts. Managed badly, they can not only take down a company but permanently rend relationships.

Lost jobs, sunk businesses, fractured families

Trust is currency — more of it usually means lower costs and fewer lawyers. A 2020 paper in the journal Frontiers in Psychology showed that higher trust in a company was associated with better business performance and higher employee incomes, longer job tenure, more job satisfaction and higher productivity.

Family businesses start out with more trust in the bank because of the clan relationships, say some family business experts. In turn, that may be a reason they do better than their non-family peers: They grow faster, are more profitable, carry less leverage and have higher valuations, according to a 2018 Credit Suisse report.

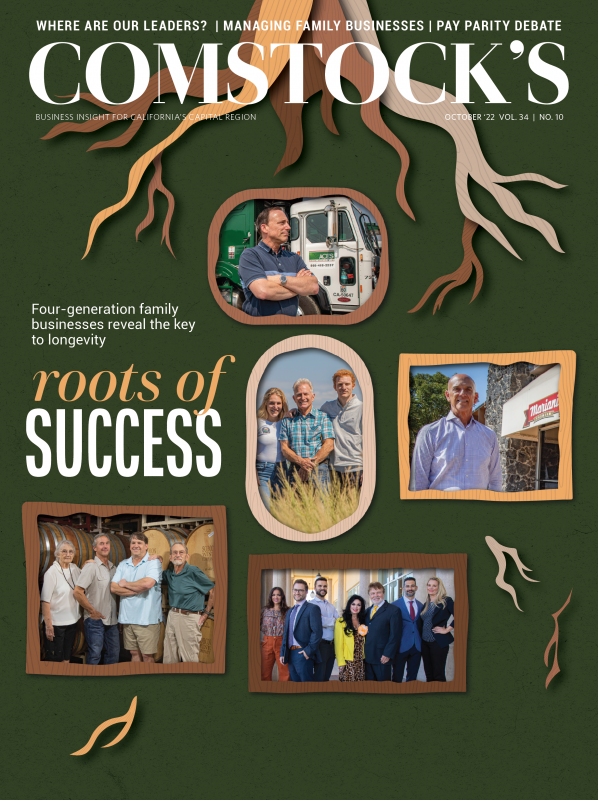

Warren, Jody and Ryan Bogle at the Bogle family winery in

Clarksburg. The siblings share a vision for sustainability and

what’s best for employees and the company. (Photo courtesy of The

Bogle family)

So a lot rides on not spending down the firm’s natural solidarity by handling clashes badly. The most obvious risk is to family connections. In a non-family run company, if you hate your boss, you can quit and never see them again — not so with a family member, says Peter Johnson, director of University of the Pacific’s Institute for Family Business.

A lot is at stake beyond the family too: When family-run enterprises get sold or fold, jobs are lost and communities lose capital, says Glassman. “We often say ‘What would a Little League game look like without family businesses?’ You wouldn’t see banners on the walls anymore,” he says.

He’s seen up close the damage untended family fissures can do. He was the fourth generation of a family business — Del Mar, a bed spring company — that had to be sold to a Fortune 500 firm because of battles between his mother and sister. “Our family business survived two World Wars and the Watts riots (in 1965 Los Angeles) but didn’t survive family disharmony,” he says.

Or take the Nut Tree roadside stand in Vacaville, a family company begun in 1921 that grew into a landmark attraction with an iconic restaurant, airstrip, miniature train and more that drew millions of visitors. By the early 1990s, surviving family members had split into factions, and a lawsuit by one side forced the Nut Tree to be put up for sale in 1996, according to an SFGate report last June excavating the history.

“Once you change the frame of mind from, ‘This is just an issue that we’re having with each other’ to ‘This is an issue that has a community impact,’ then it’s a different conversation, a different lens,” says Stella Premo, the Capital Region Family Business Center’s executive director.

The tripwires for conflict

Tension in family businesses can be more fraught than that in others because of the history. If a son or daughter is now head of sales and disagrees with a decision, the parent who leads the company may remember the tantrums they threw as a kid and chalk it up to temperament, says Johnson. Family members “have a more difficult time seeing who we are today rather than who we were five, 10, 20 years ago,” he says.

Many clashes are predictable; they happen anytime family firms are contemplating a sale, trying to figure out the next CEO or buying out a shareholder, says Glassman. Family members can also argue about how much to spend on dividends and how much to plow back into the business, says Premo. In other cases, parents want to give jobs to adult children who aren’t qualified for the roles, says Johnson. And toxic trust agreements set up by company founders — agreements that are so restrictive that they keep the next generation from adapting to a changing business climate — put firms on a downward spiral toward fissures, closure and sale, says Glassman.

Knowing all that can help leaders plan for disagreements. A theme Johnson says he’s heard over the years when family firms talk to each other is, “Oh my God, other family businesses are just as screwed up as we are.” It’s the Facebook problem — everyone assumes the pretty online pictures represent reality, he says.

Getting ahead of it

To start, family members should talk about how they see the company’s future. “If family members don’t share the same values and vision, they shouldn’t be in business together,” Glassman says. Over his years of working with family firms, he’s developed a formula for harmony: common values and vision built on a foundation of trust and sharing.

“If family members don’t share the same values and vision, they shouldn’t be in business together.”

Kurt Glassman, founding partner, LeadershipOne

Jody Bogle is vice president of consumer relations at Bogle Vineyards in Clarksburg. She’s in the third generation of family vintners, and the Bogles’ farm history stretches back six generations. Her brothers are Warren, president and vineyard director; and Ryan Bogle, vice president and CFO. Since the three took over from their parents, they’ve doubled the acreage, case volume has tripled, and the number of employees has grown about fivefold, Jody Bogle says. In 2019 the company was named American Winery of the Year by Wine Enthusiast Magazine.

Growth is good but requires more decisions. So when the siblings bring different opinions to a project, like a recent effort to rebrand, what prevents a more serious fissure is their shared past. All three grew up in the business. Company offices were in their home. As kids, they got dropped off in the vineyard with sack lunches to work all day. Bogle says they’re three different people but share a vision for sustainability and what’s best for their employees and the company. “Those are the three pillars that drive us and our everyday decisions,” she says.

Policies let a company anticipate and manage the conflict tripwires. The most important is a succession plan, says Robert Rivinius, executive director of the Family Business Association of California.

One business that’s made succession planning a practice is Holt of California, a Caterpillar dealership headquartered in Pleasant Grove. The company has managed lots of family negotiations over the years: It’s the result of previous mergers of three family-run Cat dealers. Company president Ken Monroe is at retirement age, and the company has spent four years planning for its next leader, bringing in consultants twice a year for a day and a half to meet with shareholders to formulate a strategy and holding shareholder calls between those in-person meetings.

Monroe says there’s no such thing as too much communication in succession planning and other big decisions and that it’s especially important to include in-laws in those conversations. Blowups happen when the family isn’t talking enough and someone gets it in their head that things are going south, he says.

Getting outside help in planning for and managing tension points is essential, say area experts. Consultants can ask questions like “I want to make sure I’m hearing you correctly — am I understanding what you’re suggesting?” and “What makes you believe that to be true?” says Johnson. “Whereas everybody else in the company might just say, ‘Well, that’s probably true.’” Jody Bogle says over the years consultants have worked with her and her siblings to better understand their different management styles and how to mesh those.

For all the advice on managing conflict in family firms, the biggest hurdle may be the “knowing-doing” gap — leaders know the steps but don’t actually put them into practice. “Most everybody who’s working in the business, you just get ingrained in the day-to-day stuff,” says Monroe. “It’s easy to let governance and that big picture come later … so it takes extra discipline to go do that.” Planning for conflict is about taking care of the important but not urgent, in Stephen Covey’s classic formulation.

It’s attention to those details that have kept the Benziger Family Winery a family-run firm operating inside a larger company. One longtime company policy — instituted to handle a classic conflict trigger — requires family members who want to work at Benziger to first spend time in a job elsewhere in the wine industry to learn the craft. That rule has brought in five members of the next generation — three nieces and two nephews — who are serious about the business, says Benziger.

“We’re going on seven years now, and we’re still very much the Benziger Family Winery,” he says. “Yes, the Wine Group owns us, but it’s still got the same vibe.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Is It Time for a Tax Plan?

A proposed capital gains hike could impact family businesses in transition, especially those without a strategy.

Ties That Bind

Here are 10 strategies for protecting the mental health of members of your family business.

Lineage of Success

Family businesses are the heart and soul of Little Saigon in south Sacramento

The pandemic hurt the small businesses that make up Little Saigon’s microeconomy, but business owners and their customers are hanging on.

Effective Communication Drives Family Business Success

Avoid misunderstandings and build trust with these four steps

The No. 1 problem in family business is also the same problem every other organization faces: poor communication.

Where Have All Our Leaders Gone?

In a divided country, some local leaders are serving with integrity

Across the political spectrum, this is perhaps the only thing

that everyone can agree on: The nation lacks inspiring leaders.

While leadership appears to be lacking on the national stage,

quietly — away from the spotlight — local leaders can

inspire.