As COVID-19 was bearing down on Sacramento in the spring, Vivian Pham noticed that more doctors and nurses were dropping by her restaurant in Little Saigon, fresh off a shift at nearby hospitals and in need of takeout on the way home. She thanked them for their life-saving work, but she also found that the tables had turned. They were thanking her too, just for keeping the restaurant going at a time when the pandemic was upending how people went about their lives, their work and, yes, their meals.

Pham, who runs Huong Lan Sandwiches with three generations of her family, struggled with the choice of whether to suspend operations, but in the end, she wanted to send the community a message: They were in it for the long haul.

“That is the reason I kept on going, kept it open. We have been around for so long, I can’t close,” she says. “If I close, then everybody may think that we’re giving up — and we are not going to give up.”

At the turn of the millennium, Pham’s family came to south Sacramento to open Huong Lan before the area became known as Little Saigon. The pandemic is just the latest challenge for the enclave, whose history has been dotted with struggles and successes on its way to becoming what Sacramento City Councilman Eric Guerra calls a “cultural asset” of the capital city.

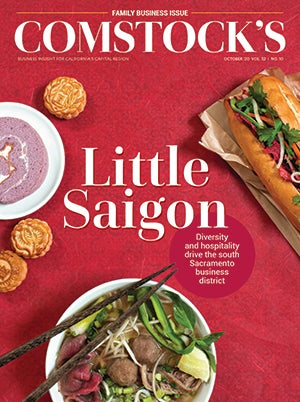

Stroll around Stockton Boulevard, especially the stretch sandwiched between Fruitridge and Florin roads, and the microeconomy is on display. At a supermarket, the aisles are lined with parsley, catfish and red lanterns. The doyenne of a jewelry store resizes rings and sells taels of gold. A doctor scrawls out prescriptions, which his daughter fills in the adjoining pharmacy. A pho shop vends the ricey cords day and night. Each of these particular businesses is owned by a family.

Little Saigon advocate Tido Hoang says families helped change the place from a neglected district to a destination, a change that is still a work in progress. He petitioned the city to make the district’s name official in 2010, not just to attract visitors but also because, to him, “Little Saigon” is an idea. It is a metonym of what he hopes Sacramento to be — a place where all newcomers start with a fair shot at making it.

What they have made, in Little Saigon, is about 200 small businesses, many of whose owners are Vietnamese, but also Chinese, Laotian, Indian, Salvadoran, Black or Slavic. As Pham puts it, what is true of the area is also true, ultimately, of the United States: “We’re all from elsewhere.”

A Mixed Local Economy

Many wind up in Sacramento because they were fleeing something — Southeast Asian war zones, Bay Area prices, the humdrum of Midwestern strip malls.

The latter applies, in part, to Jonathan Lam, who was born in Hong Kong and moved to the U.S. at 14, shuttling around small towns from Illinois to New Mexico. If he craved dim sum or pho, it required two hours of driving. Otherwise, the only options for miles were Dairy Queen, McDonald’s and gas-station fare. It was the same national brands, he says, town after town.

He was drawn to Sacramento for pockets like Little Saigon that he says add to the colorful identity of the Capital Region. In 2016, Lam and his wife, Cynthia Aung-Lam, opened Pegasus Bakery & Cafe, which has its name on its building in both English and Chinese, out of a belief that small businesses inject variety and choice into the local economy.

Jonathan Lam (right) and Cynthia Aung-Lam opened Pegasus Bakery &

Cafe in Little Saigon in 2016. The couple launched their business

out of a belief that small businesses inject variety and choice

into the local economy. (Photo by Rachel Valley)

Their gusto for running what they saw as a welcoming — and, they hoped, welcomed — business was zapped on a day in April when President Donald Trump appeared on TV and decried COVID-19 a “Chinese virus.” That night, vandals smashed through the glass doors at Pegasus, as well as the windows of four other businesses near their shop on Stockton Boulevard.

“I feel like I’m American, but people judge (the) color of my skin and are targeting us, even though we try to do good things for our community,” he says. “I can only control my own actions. So that’s how I teach my sons and my family.”

The U.S. has been slammed with a confluence of ordeals this year — medical, economic and racial — and the 2 square miles around Pegasus bear all the markings of the combined tumult. Many Little Saigon storefronts were boarded up out of fear of violence, which never came to pass, from protests after the killing May 25 of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis. These businesses were also among the first to feel the tremors of what eventually augured a recession.

The JPMorgan Chase Institute released a sample of national data in June to gauge how the pandemic hurt small businesses. Those owned by Asian Americans registered the steepest dive in revenue among all races, a 60 percent drop annualized. The institute surmised discrimination to be a factor. Businesses suffered, some through physical havoc, as at Pegasus, and others that lost customers who wondered if they could catch the virus by eating Asian food (there is no evidence it can be transmitted through handling or consuming food). The impact was also social. After the coronavirus broke out in China, Asian Americans reported an uptick in hate crimes, including a family in Fresno whose van was tagged with COVID graffiti and a woman in San Francisco struck with a glass bottle and a racial epithet.

Guerra, whose district includes Little Saigon, says the enclave was overlooked in March, when the city government earmarked $1 million in the first tranche of pandemic aid to small businesses. He says recipients tended to be downtown owners who heard about the loans early enough to apply in the two days allotted. For the second round of $15 million in June, Guerra held webinars with nonprofits including the Community Partners Advocate of Little Saigon Sacramento, and companies were given a two-week application window.

“People left for the suburbs. Those areas, who picked them up? It was the immigrants and refugees who were willing to take a bigger risk than others. And they have taken a big risk, and they have propped it up. So let’s start by acknowledging that.”

Eric Guerra Sacramento City Councilman

Over the years, the vicissitudes of a flight to the suburbs have diminished south Sacramento, including the migration farther south into Elk Grove and the opening of the Westfield Galleria at Roseville that crowded out Florin Mall. Those families who chose to keep their businesses in Little Saigon have prevented what otherwise would have been a worse economy overall for the city, Guerra says via Zoom, lighting up his digital background with a mantis-green “Little Saigon” freeway sign.

“People left for the suburbs. Those areas, who picked them up? It was the immigrants and refugees who were willing to take a bigger risk than others,” he says. “And they have taken a big risk, and they have propped it up. So let’s start by acknowledging that.”

The ‘Middleman Minorities’

By the early 1980s, south Sacramento already had a small constellation of businesses owned in large part by Chinese American and Vietnamese American kith and kin. In the decades that have elapsed, the businesses have diversified in their métier, from food focused to also mechanics, travel agencies, salons, law firms and money changers. The businesses have diversified in their cultural ties, as well, including a halal market and a Mexican dance studio.

Grocers in Little Saigon, such as SF Supermarket on 65th Street,

source niche products nationally and internationally, filling a

gap left by mainstream supermarkets. (Photo by Carly Cornejo)

Even amid all the store signage in Punjabi, Russian and Spanish, however, Vietnamese Americans made up the preponderance of shopkeepers, and in 2010, the City of Sacramento made it official: The quarter was designated as Little Saigon, the only such district sobriquet granted by the city. Campaigners wanted the name change to help brand and market the area, drawing tourists and customers.

The cost of living in Little Saigon is lower than the Sacramento average, which has been a mixed blessing. It leaves businesses with less of a buffer to endure hardship like the coronavirus-induced downturn. But it’s also what allowed mom and pops to make a foray into entrepreneurship, according to Hoang, who is the president of the Vietnamese American Community of Sacramento. He spent his childhood in the neighborhood in the 1980s, riding his bicycle around Elder Creek Road or fetching hu tieu noodles nearby for his family.

Back then, he says, a generation of immigrants was starting businesses, based mostly on grit, frugality and little to no English. They employed ethnic brethren, some with limited language skills, as well as family members, which kept costs down. Sociologists call these groups “middleman minorities,” ethnic merchants who act as conduits between the producer and the consumer. Asian grocers in Little Saigon, such as SF, A&A and Vinh Phat supermarkets, for example, will source niche products nationally and internationally, and then make them available in a single place, filling a gap left by mainstream supermarkets.

“We went there when we couldn’t afford anywhere else,” Hoang says. “We built homes, we built businesses, the businesses became million-dollar projects. It created jobs, it gave people a sense of identity.”

Also in the 1980s, Pham’s parents and her in-laws each separately moved to the United States from Vietnam, where they had determined that they could not raise their children in a post-war environment. New to the Bay Area, Pham’s mother-in-law started working at an eatery hawking banh mi, Vietnam’s national sandwich, until she was finally spurred to action by a thought that has occurred to so many families: Why not strike out on our own?

Huong Lan Sandwiches laid down stakes in San Jose and then expanded to Sacramento in the early aughts. The company now slings sandwiches at nine locations, from Rancho Cordova to Fresno, with each deli managed by a family member.

Vivian Pham, who runs Huong Lan Sandwiches with three generations

of her family, says the business stayed open after the

coronavirus pandemic hit, because “we are not going to give up.”

(Photo by Rachel Valley)

“For our parents on both sides, it’s been a long journey for them,” Pham says one evening this summer after bringing pork noodles home to her mother-in law, the matriarch of the Huong Lan dynasty. “And so, as kids, to have kept that going for them, I think they’re very proud of us.”

A History of Pluralism

Sometimes consumers want the familiarity and uniformity of a corporate chain. Other times, they want a cake with mango filling and blueberry toppings, custom made at a mom-and-pop patisserie. Lam, who has made that cake, says Pegasus gives patrons authenticity and options, like with coconut buns and Instagram-ready crepes.

“We bring them our culture, we bring them our hospitality, we bring them choices. A lot of Little Saigon, in this area it’s a lot of small businesses, different small restaurants, and they put color in the rainbow.”

JONATHAN LAM co-owner, Pegasus Bakery & Cafe

“We bring them our culture, we bring them our hospitality, we bring them choices,” he says. “A lot of Little Saigon, in this area, it’s a lot of small businesses, different small restaurants, and they put color in the rainbow.”

He has a mural to match. Step into Pegasus, and the first sight is a rainbow painting from wall to wall, anchored by the bakery’s equine namesake.

Down the street, Black, white and brown customers stop by Huong Lan, coolly familiar with its many Vietnamese dishes, but the restaurant is also changing palates. Pham laughs as she recalls a diner who grimaced at hearing about headcheese, a meat jelly made from various parts of a pig, but tried it anyway.

Variety comes from family businesses like these. But across the U.S., after decades of corporate mergers and expansion, it has become less and less likely that such small ventures will survive. To take one indicator, the Kauffman Foundation calculates what percent of new businesses actually hire staff within two years of forming. In California, that number has declined nearly every year since 2005, to 15.6 percent in 2018, according to the foundation’s “2018 New Employer Business Report.”

These businesses are vital to the continued development of Little Saigon, Guerra says, especially if the Capital Region is going to tackle broader problems such as sprawl, pollution and homelessness.

They are a reminder too, that Sacramento’s is a history of newcomers, he says, which has been the case for the better part of two centuries. After the Maidu and Miwok people, white and Chinese settlers came to the valley in the gold rush, followed by arrivals linked to the end of slavery, the Dust Bowl, the multiple waves from Latin America and the Vietnam War. They came for mobility of all kinds — geographic, social and economic.

“It provides a sense of home,” Guerra says of the district. “All of these businesses that are on the boulevard bring that sense of welcomeness.” He aims to make Little Saigon a better-known destination, a vital stop on the itinerary of travelers to the California capital.

It is a continuation of work that denizens have been doing for years, according to Hoang, who also works with his siblings at Tido Financial, the financial advisory business he founded. People used to drive out of downtown Sacramento on Highway 99 and pass by “a place no one wanted to pay attention to,” he says. Today, the neighborhood still has to contend with blight, depressed property values, crime and underserved populations. But families also have brought restaurants, festivals and temples to the working-class ZIP code. In a time of pandemic, they donated food and masks to those with less. In more salutary times, they held networking mixers and free classes in tai chi or computer literacy.

“We worked hard,” Hoang says of the evolution over the years. “We changed this from a place that was undesired to now, a place where people look forward to coming.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.