A rumor of impending layoffs circled the newsroom in the weeks before they hit, but the reporters didn’t know the size of the reduction, or who would be targeted.

Ed Fletcher, a general assignment reporter at the Sacramento Bee for the past 18 years, was getting ready for work on Tuesday, April 24, when he noticed a Facebook post from his colleague Tom Couzens.

“I just received the expected call,” wrote Couzens, a sports editor and 33-year Sac Bee veteran. “I am not sad for me, but for our industry and the thousands [that] have been let go.”

Minutes later, Fletcher says he received a call from Lauren Gustus, regional editor for McClatchy’s West region, who explained Fletcher’s own termination in the context of a greater restructuring effort by the parent company of the Sac Bee and 30 other newspapers throughout the country.

The Sac Bee newsroom has shrunk 63 percent since 2006, down to 105 newsroom staff. This most recent round of layoffs represented a 15 percent reduction from a year ago. It included 20-year sports columnist Ailene Voisin, two business reporters and its cannabis reporter. Sacramento currently lacks a full-time journalist focused solely on the city’s emerging cannabis industry, with its rampant black market and startup enforcement agencies. The past year alone saw the Sac Bee replace its publisher and executive editor. A prior round of layoffs, in May 2017, slashed a dozen reporters from the news, arts and sports desks.

McClatchy’s printing press, located in Midtown Sacramento, circa

2016. (photo: Ken James)

The recent downsizing is collateral damage to what McClatchy executives call the company’s “digital turn,” as the company focuses on a digital product line while cutting expenses, regionalizing operations and hiring more digital- and data-savvy reporters. The opening of a second virtual and augmented reality R&D hub in Sacramento, New Ventures Lab, is a symbol of McClatchy’s next chapter.

Executives do not forecast an end to the print product, at least not publicly, but this transformation from a newspaper company to a tech business marks an unavoidable pivot that plows the elder media firm into a crowded and cutthroat arena. Decades-long journalism careers are suddenly ending as the product enters its unpredictable metamorphosis. If successful, McClatchy may ride along the helm of an exhilarating shift in the delivery and consumption of news.

If not, Sacramentans could lose their paper of record. The Sac Bee is often slammed by readers for floundering in its public watchdog role or swinging too far to the left. But even when those gripes are valid, the consequences to losing a paper of record are incalculable. Doctors are regularly sued for malpractice, but nobody wants to live in a community without a hospital. The Sac Bee is almost as old as the city itself. Its demise would be an alarming blow to civic transparency, says Dan Walters, who worked as a Bee columnist for 33 years.

This transformation … marks an unavoidable pivot that plows the elder media firm into a crowded and cutthoat arena.

If the daily newspaper goes away, “The people in the school board and the administration and the unions will feel free to do any damn thing they want to because they know nobody’s looking over their shoulder,” says Walters, who now works for the journalism nonprofit CALmatters. “That’s what gets lost.”

Locally Rooted Legacy

With a 161-year history in Sacramento, McClatchy is one of the nation’s largest newspaper chains, with 30 newspapers across 14 states. More people than ever are reading its journalism: While its daily newspaper circulation has fallen by 52 percent over the past decade, the number of visitors to McClatchy websites has grown significantly over that time. On average, McClatchy fetches over 75 million unique visitors each month, up almost 200 percent from a decade ago.

But McClatchy’s revenue has fallen by approximately 60 percent since its peak in 2007, and the company has endured annual losses for the past three years. The publicly traded company has become a case study for the troubles of the American newspaper, joined by other signature newspaper institutions of California. This year alone, the Los Angeles Times unionized following years of downsizing. Digital First Media, which owns 16 regional papers in California including San Jose’s The Mercury News, cut a third of its total statewide editorial staff. While the nation’s largest newspapers have experienced large boosts in digital subscriptions following the election of President Donald Trump, overall circulation for U.S. daily newspapers has dropped every year since 1988, according to the Pew Research Center.

But the widespread malaise hanging over the news industry was clear from the air on a bright day in mid-May, when McClatchy celebrated the launch of New Ventures Lab. The space is to be a high-tech testing ground where journalists and technologists can experiment with virtual and augmented reality — two developing mediums that cast users into computer-simulated environments. Wine flowed as local tech luminaries and city officials explored the “video lab” at the newly-renovated train depot, with representatives from Google and YouTube in the mix. Attendees tried on Oculus VR headsets to view samples of upcoming McClatchy projects. Stickers featuring McClatchy’s new slogan, #ReadLocal, were scattered across black-clothed tables.

Wearing a dark suit and clear-rimmed eyeglasses, McClatchy CEO Craig Forman addressed the crowd, linking this new venture to the company’s commitment to local journalism. He described Meghan Sims, who is leading the NVL project, as the innovative heir to Eleanor McClatchy, the third-generation family leader who lifted the company to greater prominence throughout the mid-20th century.

A paper boy delivers the Sacramento Bee in 1950. (photo: courtesy

of center for sacramento history sacramento bee collection)

“We’re deeply committed to this city and to independent journalism in the public interest,” Forman told the crowd. “This space demonstrates our dedication to innovation and reinvention.”

Even if the digital turn proves successful and McClatchy can stabilize its revenue and expand again, the turnaround will bookend an American staple. If you lived in Northern California at any time over the last 150 years, the internet was delivered to your doorstep every morning, and it came in the form of the Sacramento Bee. At its height in 2004, the paper’s daily circulation reached almost 300,000. Throughout the 20th century, the Bee (including the Fresno Bee and the Modesto Bee, which were launched in the 1920s) extended to nearly 100 small towns and cities, with stringers writing dispatches from across the Central Valley. At its height, the paper could be found in newsstands from the Oregon border to San Diego. Love it or hate it (and there have always been haters), the Bee was fundamental to the California experience. People would start reading the front page over breakfast, then resume at a coffee shop or work. The newspaper was ubiquitous from city to city. In the Sacramento region, disc jockeys read the Bee’s reporting aloud on local radio stations during the day, and television news anchors did so at night.

“It was information, opinion, news, comics for the kids, [baseball] box scores. It was a real part of life for everyday people,” says Steve Wiegand, author of Papers of Permanence: The First 150 Years of The McClatchy Company, in an interview with Comstock’s.

As the city matured, the Sac Bee guided some of Sacramento’s most vital public conversations. It fought for the creation of the Sacramento Municipal Utility District after locals felt slighted by PG&E. It covered the earliest discourse that preceded the statewide water plan. More recently, the paper broke news surrounding the Oroville Dam crisis, the killing of Stephon Clark and the capture of the Golden State Killer — the latter story occuring the day after the recent round of layoffs were announced.

“To say McClatchy will be able to survive and evolve in a digital platform — we don’t have that answer,” says Keith Herndon, author of The Decline of the Daily Newspaper: How an American Institution Lost the Online Revolution, in an interview with Comstock’s. “This transition is ugly and disruptive, and we are in the middle of it,” Herndon says.

The Dark Knight

There are reasons to harbor hope that Sacramento’s premiere newspaper company can slug away competitors long enough to catch its breath and grow again. But if McClatchy is ultimately swallowed by a techie takeover, fingers will fly at the firm’s former leader, whose youthful exuberance embodied the company at the crest of its confidence, right before the fall.

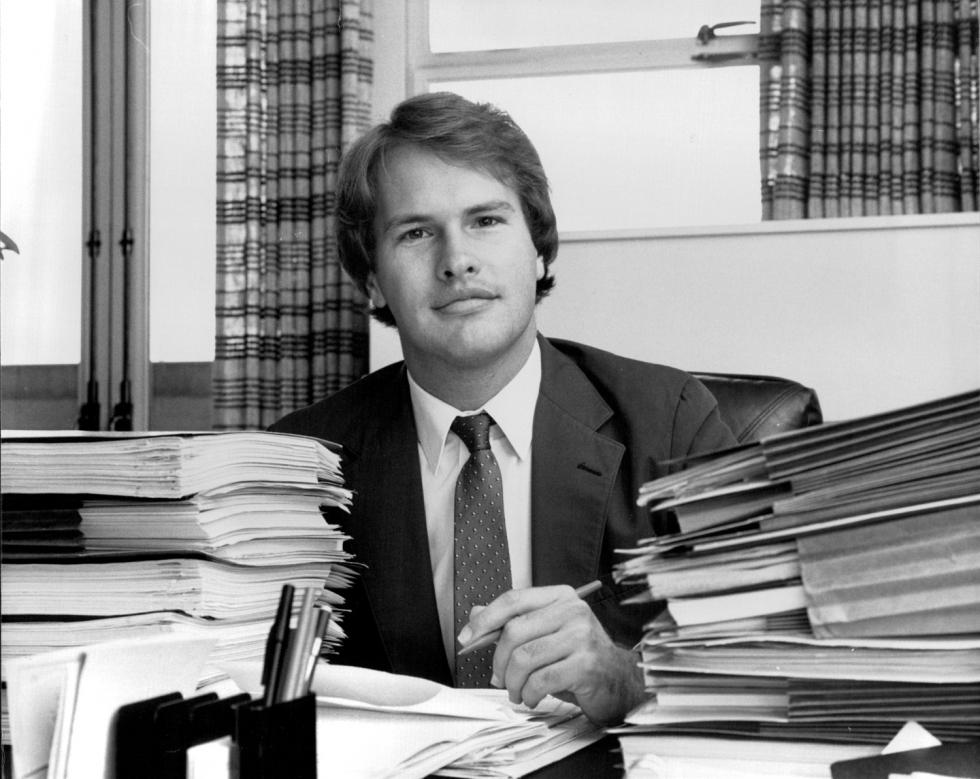

Gary Pruitt looked younger than his 27 years when he first arrived at McClatchy in 1984. Blessed with a playful confidence and breezy blond hair, he possessed a fierce intellect but looked the part of a handsome surfer. He first gained favor with the newsroom as legal counsel and a First Amendment soldier for McClatchy, before working his way up to chief executive officer in 1996.

Despite his good looks and extreme confidence, Pruitt was well-liked by executives and reporters alike; he appeared to have McClatchy’s public service mission flowing through his blood. He’d greet journalists by name, smiling and waving as he strolled past them in the cafeteria. Walters describes Pruitt as a “go go-getter” type who was “trying to make a name for himself.”

Gary Pruitt shortly after joining McClatchy in 1984.

“He was sure of himself and kind of interested in doing big things and making big deals,” Walters recalls.

Pruitt himself described his business strategy in a 2001 interview with Editor & Publisher magazine, saying, “The idea is to remain lean and efficient even in good times so that we can ride out the bad times and avoid that kind of boom-and-bust scenario, which leads to numerous layoffs.”

At the time, McClatchy had a reputation on Wall Street for playing it safe and only purchasing metro newspapers that dominated their high-growth markets. Pruitt would ultimately use that philosophy to justify the company’s largest and riskiest purchase on March 12, 2006. On that day, McClatchy bought the nation’s second-largest newspaper chain, in an infamous transaction that one analyst called “a dolphin swallowing a small whale.”

“No newspaper publisher woke up to the power and challenge of the internet from 1995 to 2005.”

Alan Mutter, media economics professor, UC Berkeley

Howard Weaver, the company’s chief editorial executive at the time, recalls that first discussion of the deal taking place on a Tuesday in early November 2005. A few McClatchy executives sat around the table at Crepe-ville in Midtown Sacramento, when chief financial officer Pat Talamantes pulled out his BlackBerry to show his colleagues a message from the boss.

“Knight Ridder is in play,” Pruitt wrote in the email. “Let the games begin.”

Knight Ridder was an industry titan. The San Jose-based company posted more than double McClatchy’s revenue. News had leaked to Pruitt that Knight Ridder’s largest shareholder, dissatisfied with the company’s stock performance, was pushing its board to put the publicly traded company up for sale — a sign that economic headwinds had begun to constrain the newspaper business.

Knight Ridder published The Mercury News, the Contra Costa Times and 30 other daily newspapers. The sale would mark the second largest takeover in U.S. newspaper history. McClatchy lacked the prestige of Gannett, the nation’s largest newspaper chain, and other industry giants like The Washington Post Company, but it was widely viewed as a rising star. From its Sacramento headquarters, McClatchy published the Bee and 28 other papers. It had seen 20 consecutive years of circulation increases through 2004, and a decade of stock growth that outpaced all its peers. At the time, the U.S. newspaper industry was still yielding profit margins of about 20 percent — double the average of the Fortune 500.

“[The purchase] was a little bit of empire building, but it wasn’t like everyone was greatly ambitious and wanted to become Rupert Murdoch,” Wiegand says. “The idea was to swallow something big, or get swallowed by something big.”

As McClatchy considered the biggest purchase in the company’s 149-year history, executives spent months filling up to seven days per week with exhaustive research. Upper management drew economic models to forecast every conceivable problem. They considered economic recessions, hiccups in cash flow, weakening news markets and drops in advertising.

Eleanor McClatchy led the company for over 40 years, from

1936-1978. (photo: courtesy of Mcclatchy)

“It was all thought out. It wasn’t reckless or done for any ego reason,” says Weaver, former vice president for news. “We thought we could make McClatchy stronger and bring McClatchy journalism to new communities.”

The Knight Ridder auction initially attracted interest from major publishers like Gannett, but in the end, McClatchy was the only large newspaper company to submit a final bid. The $4.5 billion sale nearly tripled McClatchy’s revenue, but also saddled it with debt. After the company successfully offloaded 12 of the Knight Ridder papers in slower-growth markets, its debt rested at about $3.2 billion.

That year, the company rewarded Gary Pruitt with $5.6 million in total compensation, including a $1 million bonus for the Knight Ridder purchase. Pruitt’s team immediately began looking ahead to a near future when newspapers and advertising would be delivered on people’s cellphones.

To this day, a debate persists about the outcome of the Knight Ridder purchase. Weaver argues that higher-performing, former Knight Ridder papers protected McClatchy from the worst of the down years. Others say that debt from the deal bound McClatchy like a straightjacket, leaving the company no choice but to cut its way out.

U.S. home prices peaked four months after the sale, portending a subprime mortgage crisis that would hit Sacramento harder than any region in the state. And while online advertising increasingly unsettled the newspaper business model, few predicted the devastation to come from the world’s largest internet companies.

The End of an Era

“No newspaper publisher woke up to the power and challenge of the internet from 1995 to 2005,” says Alan Mutter, a media economics professor at UC Berkeley. “While revenues were climbing, they pocketed the profits and distributed it back to shareholders.”

Warning signs were clear, however, from the journalists themselves. Across the globe, reporters were publishing prophetic stories about the slow demise of their own industry. Online news was gaining popularity, but digital ads only brought pennies on the dollar compared to the printed product. Craigslist had already been around for over a decade. Its mass production of free classified ads had spread to 35 countries, inhaling an estimated $50 million in advertising revenue out of the Bay Area alone. Facebook, not yet a threat to the core newspaper revenue model, introduced its News Feed in September 2006, an innovation that would slowly replace the nation’s newspaper distribution system pioneered more than 200 years ago.

Subscribe to Comstock’s and support local journalism

McClatchy executives initially envisioned McClatchy newspapers fulfilling a role on the web that may have worked if not for the rise of Facebook. Under the vision, urban residents would become citizen journalists who wrote local community news, such as little league scores, out of hobby on personal web pages and online forums. Reporters at a paper like the Bee would cherry-pick from those posts, and the most engaging and important information would rise to top its homepage. That plan, outlined in Wiegand’s book, arrived a few years before a Silicon Valley tech firm became the online public square to every U.S. city.

“Ultimately, Facebook gave that stuff away free,” Wiegand says. “You couldn’t build a business model to do what Facebook does and still have the [original] journalism.”

Two years after the Knight Ridder sale, the collapse of brokerage firm Bear Stearns sent global stock markets rolling, and the Great Recession was underway.

Newspaper print advertising fell, investors fled, and McClatchy’s stock cascaded in value (as of this writing, stock prices for the company are at $9.70 a share, compared to $76.05 a share at its peak in 2005). The company cut 1,400 jobs in its first-ever round of mass layoffs in June 2008. By mid-September, the company slashed another 1,150 jobs. Remaining staff saw pay cuts and a hold on their pensions. Even the company jet was sold, with all extra proceeds funnelled toward paying off the debt. Thousands more staffers would leave McClatchy over the following years through layoffs and buyouts.

“I hated [the layoffs], but I knew there wasn’t an alternative,” says Weaver, who retired in 2008, citing an expertise in building newspapers, not tearing them down. “It was killing me. It hurt.”

When the Sac Bee asked Pruitt in September 2008 whether he had buyer’s remorse about Knight Ridder, he answered morosely. “It’s hard to claim it’s a good deal when you see the stock performance.”

Together, Facebook and Google control more than 60 percent of the digital market.

By summer 2009, McClatchy had cut 35 percent of its workforce from the prior year. The Sac Bee reported at the time that the cutbacks were commensurate with reductions at other newspaper chains, triggered by the recession. Pruitt stepped down from McClatchy in early 2012. He took a job as president and CEO of the Associated Press, a position he still holds. (The A.P. did not respond to a request to interview Pruitt for this article.)

“People eventually came to the conclusion that Pruitt made a bad deal. He drove us in exactly the wrong direction, and we’ve been dealing with it ever since,” says Ed Fletcher. “Some people are surprised that he is still working in media, having such a failure on his résumé.”

Dawn of a New Age

A successful digital pivot on the part of McClatchy will require a delicate dance. Growth in its online audience is a point of encouragement. Executives predict 2018 will mark the first year that revenue from digital advertising eclipses newspaper advertising. Newspaper ads make up a quarter of the company’s total revenue, down from two-thirds of the pie a decade ago. But while revenue from digital subscriptions is steadily rising, it doesn’t make up for the revenue losses resulting from the decline of newspapers. Daily print circulation has dropped 43 percent over the past decade and Sunday circulation 33 percent, according to McClatchy CFO Elaine Lintecum. Digital subscriptions continue to grow, but print subscriptions combined with single-copy sales still make up more than two-thirds of all the company’s revenues generated from readers.

Meghan Sims, McClatchy’s director of strategic video initiatives

photo: Tom Huyn

And while at no point in living memory could the finances of newspapers be considered stable (there was the competitive assault from radio in the 1920s, television in the 1950s and internet in the 1990s), the loss of digital advertising to Google and Facebook may mark a fatal blow. Together, those companies control more than 60 percent of the U.S. digital ad market — and newspapers are no match for the advertising rates of internet behemoths.

Everything comes down to scale, says Keith Herndon, a journalism professor at the University of Georgia. “Google and Facebook can scale advertising rates across hundreds of millions of users,” Herndon says. “If a local advertising publication has to meet that rate, they cannot scale it.”

With the traditional revenue model becoming obsolete, McClatchy is following a more bountiful path that’s recently caught the public spotlight for its surreptitious use by tech firms like Facebook: using consumer data to tailor ads to targeted audiences. McClatchy’s newspaper ads department is morphing into a more sophisticated digital advertising and consulting agency. The company’s other highly promoted venture is in augmented and virtual reality, a medium that is projected to grow by 100 percent or more each year for the next four years.

“We are deeply committed to this city and independent journalism in the public interest”

Craig Forman, CEO, McClatchy

Much the way that Pruitt personified the company’s swagger of the 1980s and 1990s, Forman, who joined McClatchy’s board of directors in 2013 and became president and CEO in early 2017, epitomizes McClatchy’s reach toward digital: He has a background in both tech and journalism, lives in San Francisco and commutes to Sacramento in a red Tesla. A former Wall Street Journal correspondent and Tokyo bureau chief, Forman went on to lead audience development and media divisions for EarthLink, Yahoo and Time Warner.

The rest of the company’s 12-person board of directors includes a Google executive, the former CEO of Etsy, and the founder of a virtual reality startup.

Forman told an audience of about 13,000 digital developers and engineers at an Adobe summit in March that McClatchy’s new mission is to find products that “save you time, save you money or delight you in some surprising new way.” The company will “innovate with intention and less with pure speculative experimentation,” he told the Las Vegas Crowd.

But the reality of virtual and augmented reality is that their ability to be monetized by news organizations is still theoretical. The medium is in its infancy and not yet significantly profitable. For its part, McClatchy’s video views for the first quarter of 2018 are significantly higher than the same period last year (40 percent of total views in 2017), with video revenues up almost 50 percent during the same time.

Perhaps the two most publicized examples of news-related VR programming to date, The Daily 360 by The New York Times and a VR feature in the 2018 Winter Olympics, were both products of a Samsung sponsorship. But the emerging technology is a powerful storytelling medium that shouldn’t be ignored, says Laura Hertzfeld, director of Journalism 360, an AR/VR initiative by the Online News Association.

Technologist Julian Rojas tests audio compatibility with the

Oculus Go headset at New Ventures Lab in Sacramento. photo:

melanie jensen

“If we don’t invest, we will never know if there is a revenue-earning potential,” she says.

For the last two decades, newspaper companies have missed every major technological advancement, and the lack of aggressiveness cost them their business model, says Alan Mutter, a new media ventures consultant and former assistant managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle.

Immersive video “is highly unlikely to move the needle for the McClatchy company, and yet they would be remiss if they didn’t try,” he says.

Tech-Savvy Savior

McClatchy’s New Ventures Lab, formerly known as Video Lab West, sits on the second floor of the newly renovated depot at Sacramento’s downtown train station. The space, which opened in mid-May after more than a year in the making, is a mashup between a movie studio and a modern open-design tech office. A couple large soundproofed rooms will act as labs for various experiments in virtual reality. In true tech fashion, just about every piece of furniture and equipment is on wheels.

The idea is to have in-house journalists and technologists working with a rotating group of “storytellers-in-residence” to create coverage that is more immersive and cutting-edge. The name change seeks to convey that McClatchy will use the space to host video R&D, podcasting, events and corporate partnerships. A separate endeavor, the McClatchy New Ventures Fund, will invest in related seed and early-stage startups.

Here’s how the lab could potentially work in one of its markets: Instead of covering Sacramento’s proposed streetcar with a print story and a companion video of another streetcar rolling through an urban neighborhood, a project by the New Ventures Lab could allow users to lift up their smartphones and actually see a computer-generated Sacramento streetcar in motion. The New Ventures Lab could even host an event where attendees strapped on a headset and walked around inside a simulated streetcar.

“It’s the birth of a medium. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing. We’re here for the start of it, and we’re excited to see where it’s going to go,” says Sims, who is McClatchy’s director of strategic video initiatives.

Sims came to McClatchy three years ago to help launch its original Video Lab in Washington, D.C. The idea was to have a central video production space for all the McClatchy newsrooms. Using immersive technology, McClatchy has already brought viewers inside a prison in Guantanamo Bay and the tunnel leading to the field of a North Carolina State football game.

In 2016, videographers teamed up with reporters at the McClatchy-owned Star-Telegram of Fort Worth, Texas to cover a true-life version of “Friday Night Lights” about a football team in Aledo, Texas. The documentary was released straight to Facebook Watch, the company’s on-demand service, and attracted 23 million views last year. The following year, McClatchy won a Pulitzer Prize for its Panama Papers project that involved a collaboration of 100 media outlets, and the Video Lab illustrated the story about offshore banking with a motion graphic video.

The company maintains that everything it does supports public interest journalism — that’s the flagship product that keeps readers and advertisers interested, says Elaine Lintecum, McClatchy’s chief financial officer. As a symbol of that commitment, McClatchy has started stamping headlines with its #ReadLocal hashtag on social media. Lintecum, who joined the company in 1988, notes that the growing revenue from digital ads and subscriptions marks undeniable progress toward “supporting local journalism and jobs.”

“That’s all important,” she says. “But we don’t have a crystal ball for when the bend in the revenue curve will straighten.”

The Beat Goes On

For most of the 20th century, print editors splashed the news they deemed most influential to the public interest over page A1. The more indulgent gossip, the predecessor of clickbait, was relegated to the back pages. Each day, newspapers were constructed like an album, with a predictable flow of beginning, middle and end.

Craig Forman addresses the crowd at the launch of New Ventures

Lab in May 2018.

The internet swung a populist axe into those divisions. Readers had always questioned the authority and political bent of the self-appointed gatekeepers of information; the web broke it all down. No longer was “most desirable,” as decided by readers, separate from “highest quality,” as determined by editors. The focus shifted toward maximizing website clicks on each article. The production of the daily album shifted to a focus of churning out hit singles that might become globally popular.

Local news won’t go away. But the fear from journalists and editors — beyond self-preservation — is that when local news isn’t brimming with political sex scandals and protests over police killings, it serves a less sensational public interest role that keeps residents informed and community leaders accountable. The rush to embrace high-tech products may be necessary, but the concern from Wiegand, the biographer who literally wrote the book on McClatchy, is that for 161-years, McClatchy’s civic value has been its ability to distill the news into articles that inform readers when authority figures are trying to shade the truth. McClatchy is now laying off veteran reporters while it hires programmers with different skill sets.

McClatchy “wasn’t just a business. It was a public institution with public responsibility,” Wiegand says. “Now that it’s in a fight for survival, I don’t have a good feeling about how it’s going to come out of this era and still maintain its place and its sense of self.”

Print media is undergoing the same disruption as the music industry because consumers are now accustomed to getting the product for free, except in this case, it’s worse. The public hasn’t turned against musicians with accusations of, “Fake songs!” And if a weakened McClatchy were dethroned by a scrappy startup, there’s no reason to suspect the new players would continue the routine (and often more boring) policy coverage that has never been worth its weight in website clicks.

McClatchy is at least trying to protect its once-celebrated daily album with trenchant public-interest reporting; whether it strikes the right balance on any given day is a different story. If the McClatchy album vanishes, who knows? Maybe a richer, more level melody will replace it. But if not, we’ll all slip further into the absorbing white noise of partisan outrage and entertainment — where truth used to be.

–

Recommended For You

Get it in print

Support local journalism: Subscribe to Comstock’s and get our high-quality print magazine delivered directly to your door!

Get our newsletter

Keep up to date on all things Comstock’s, including the best print and web-only journalism, commentary and analysis from throughout the Capital Region. Sign up for our email newsletter by filling in the fields below. And don’t worry — we’ll never sell or share your information with others.

Comments

Great artcle. The stock price comparison is understated; MNI had a 1:10 split, which would make the comparable price today @ less than $1 per share. The larger concern is that over $400mm in bond debt comes due at the end of 2022. MNI is paying $80mm per year to service the bond debt, and will need to bank a similar amount each year to pay off the bondholders. That is a very tricky needle to thread when revenues continue to decline. I hope they can do it.

Sounds like an evolving environment full of challenges and perhaps not enough opportunities.

Excellent article, great reporting. As a Bee staff writer for 13 years (1969-81), blessed to work for the great Frank McCulloch, I find the terrible cutbacks and slow decline of an important civic institution deeply troubling and personally painful. I remember covering long, boring city council and school board meetings, legal and legislative hearings, spending hours, days, weeks combing (then all-paper) records of local and state agencies for investigative articles that resulted in major revelations about mental health, foster care, juvenile justice, state prisons. And significant change in those public agencies often occurred as a result. I hope these high-tech innovations will help the Bee dig out of the hole Gary Pruitt helped put it in, but, like many other longtime journalists, I question whether it can be done without continuing to compromise the critical role that “on-the-ground” reporters play, slogging through public records and government meetings, asking the important questions, TALKING to real people, demanding answers, ferreting out the truth — protecting the bedrock principles of serious journalism and the public’s right to know. Ultimately, as I often tell my CSUS journalism students, it’s about the reporting, the writing, the facts. It’s not easy, and it’s not always fun — nor guaranteed to generate clicks. But it’s critical to our democracy, especially in this fraught political environment. Thanks for this great article, so timely and important, by a talented young journalist (a former UC Center-Sacramento student I was privileged to teach/mentor) who has pursued a stellar journalistic career in very tough times.

Great article - with very sad news. Without reporters in a free press the public will be less aware of what is happening. When that happens very shady deals and deceptive practices will run rampant.

I love the Bee but this is not the first time I've read a story like this. Newspapers need to make some bold changes to survive. Although a lot thinner, the Bee today looks a lot like the Bee did in 2006. What have you got to lose? Adapt or die!

Excellent article. You wrote: "Executives do not forecast an end to the print product, at least not publicly..." The last two times I have called Sac Bee about delivery problems related to the physical newspaper, the call center folks tried hard to get me to switch to digital-only. I would do so if we were not trying to restrict the "screen time" of our kid, who joins me in reading the newspaper over breakfast.

20 years as a press operator the Modesto Bee I saw the decline. The worst insult came shortly after the Knight Ridder deal when Gary Pruitt gave his state of the Bee address. He always came to each individual paper and gave it in person. He would always start with a classic rock song and finish with a classic rock song. His last State of the Bee was via video. He attempted to smooth over some bad decisions. He ended the talk with Mic Jagger's "You don't always get what you want". Shortly after that it was announced that the Modesto Bee would be printed in Sacramento. A couple years later the Fresno Bee printing was sent to Sacto and finally the Merced Sun Star.

Bad deals were made such as buying the Minneapolis Star Tribune in the 90s and later selling it off at a great loss to get funds to buy K/R. After the K/R purchase he sold off money making papers... they may not have been growth papers but they ran at a profit. The Modesto Bee went from over 900 employees in its heyday (2006 ish) to a couple full time staff and most of the reporting is done by on call/ part time and contract people. They cut up a $10 million printing press after they sold what parts they could. Once was a time when a city was proud to have its own paper printed by its own press. R.I.P. the printed word.

Blaming this on Gary Pruitt seems silly. I doubt he could do a $4.5 billion deal without board of directors approval. It turned out to be a bad deal, for sure, but blame rests with the board (which included Pruitt) too.

I am or was until 3 weeks ago, a career tech person with McClatchy. I first walked in the door of the Modesto Bee some 37 years ago January 1981. As you can imagine, I saw a tremendous change in technology from that time forward. The eighties and nineties were the good years of prosperity and continual climb up the career ladder. The eighties were especially rewarding as the company was headed up by CK McClatchy and we were still a family run company. I remember CK coming down for the annual state of the Bee and how positive the message was. I would always make it a point to chat with him and he was always kind and generous with his time and even remembered my name from year to year. Were were like family and were treated with the utmost respect and lavished with parties and numerous company sponsored events. It was truly the Golden age of newspapers and those days are long gone. Fast forward to The end of June this year. I was summoned to a digital call at which time I was informed my position was eliminated. I was given less than 2 weeks notice after 37 years of dedicated service, no watch, no formal goodbyes just pack your desk and hit the street, all 3 months before my 62nd Birthday. I’m not shocked but I am disappointed I was not able to retire with dignity as I was so close to the finish line. The print news business as we know is dead along with loyalty to employees that built and ran the company. And just like that he was gone.....

I was surprised that the Minneapolis Star-Tribune saga was not in the main body of the story. The board (wrapped up in Pruitt's aura) paid an exorbitant $1.2 billion and sold it six years later for $600 million.

The papers (like the San Jose Mercury) they sold off had strong unions, too. McClatchy did NOT like dealing with organized labor.

If CK McClatchy had survived, Pruitt would not have had the board in his pocket. A likeable guy, he would have been on the cover of Fortune magazine if his ideas had came to fruition.