PEOPLE LOVE TO DEBATE THE HOUSING CRISIS. Who’s to blame? What should be done? How come I can only afford to live in a shoebox? There are no easy answers. Yet one thing is undeniably true: Housing challenges are not new. “Housing is cyclical,” says local historian William Burg. “In Sacramento, we tend to have boom-and-bust cycles. We’re gold rush folks.”

So to frame the issue with historical context, we’ve put together a timeline of certain key events in the region’s history of housing, from John Sutter to Proposition 10.

1849: THE FIRST BRICK HOUSE

George Zins was a brickmaker. He used a team of oxen to haul his bricks to Front Street, where the Embassy Suites by Hilton currently sits, and built a two-story, 35 feet by 60 feet home. And thus began the Sacramento housing market. The house cost $40,000 at the time, or around $1.2 million in today’s dollars. (California housing: never cheap.)

1849: GOLD RUSH

Thousands of gold-crazy speculators stormed into Sacramento, eager to make a fortune. Most of them lived in tents. “San Francisco and Sacramento had become the state’s two biggest cities overnight, and there wasn’t any housing. That was our first housing boom,” Burg says. “The number of units available: zero. Everything was expensive. Land was expensive. Food was expensive.” Thus begins the core problem that would persist for the next 160-plus years: People want to live here, but there aren’t enough houses.

1850: SQUATTERS RIOTS

New residents in Sacramento, desperate for places to live, began building log cabins on vacant lots — even if these lots belonged to people like John Sutter. Called squatters, these folks formed the Sacramento City Settlers’ Association and contested the legality of Sutter’s land grants. (A defender of theirs: James McClatchy, Sacramento Bee founder.)

Sutter wasn’t thrilled. “Notice to Squatters,” he wrote in a stern warning in the Placer Times, a triweekly paper that operated from 1849 to 1850, “All persons are hereby cautioned not to settle, without my permission, on any land of mine in this Territory.” The squatters dug themselves in, and the words escalated to violence.

“At the corner of Fourth and J streets the Squatters were met by the Mayor [Hardin Bigelow], who ordered them to deliver up their arms and disperse,” recounts “History of Sacramento,” written in 1880. The squatters didn’t budge. They aimed their guns at the mayor. They fired. “He fell from his horse and was carried to his residence, dangerously, if not mortally, wounded.” (The mayor lived; others were killed.) The government backed Sutter’s grants; the squatters were forced to move.

1850: FLOODS AND LEVEES

Enter the floods. “On Thursday morning, the entire city, within a mile of the embarcadero, was under water,” reported the Jan. 19, 1850 Placer Times. Residents drown and “many persons have lost from 10 to 50 yoke of cattle each.” Something needed to be done. So the city began constructing levees (a project that would take another 60-plus years), which gave the literal foundation for residential development. Housing construction began.

1869: COMPLETION OF THE CENTRAL PACIFIC RAILROAD

The Central Pacific Railroad ran from Sacramento to Utah as part

of the first transcontinental railroad. (photo courtesy: Center

for Sacramento History)

On May 10, a golden spike completed the transcontinental railroad and “put Sacramento in the national transportation network and made the city a terminus for people, freight, mail, and locally grown produce headed for the tables of the East,” explains Steven M. Avella in “Sacramento: Indomitable City.” In just two decades, the city’s population tripled — from 9,000 in 1850 to 27,000 in 1870 — and more trains meant more growth and more demand for housing.

1880s: THE VICTORIAN ERA

Tents are out, mansions are in. The ritzy streets of downtown became dotted with luxurious Victorian homes, such as the residence of Albert Gallatin, on 16th and H streets. “The home embodied many of the finest features of Sacramento’s Victorians with gilded ceilings, hardwood floors, and odd shaped rooms,” writes Avella. In 1903, Gallatin’s mansion would become the governor’s residence until 1967, when “California First Lady Nancy Reagan refused to live in ‘the old fire trap.’”

Albert Gallatin’s mansion, built at the turn of the 20th century,

ultimately served as the Governor’s Mansion until the late 1960s.

(photo courtesy: Center for Sacramento History)

1900: BIRTH OF THE ELECTRIC STREET CAR

Thanks to this new technology, it was possible to work downtown and commute to new houses in the “streetcar suburbs” like Oak Park. The city begins expanding outward, and the homes follow.

1910: LEVEE BREAKTHROUGH

“The really big levee improvement projects happened around 1910,” says Burg, adding that they were possible only through government investment. The new levees, like the streetcar, expanded the area for housing.

1923: GETTING INTO THE ZONES

The City of Sacramento begins to carve out different zones, which would eventually become known as categories like R-1: Single-Family Residential Zone, C-2: General Commercial Zone and M-2: Heavy Industrial Zone. This would have repercussions for the next hundred years, and critics now argue not enough of the map is allocated to housing. “The big glaring issue is that we haven’t built enough homes. The supply of housing is not enough to meet demand,” says David Garcia, policy director at UC Berkeley Terner Center for Housing Innovation. “I always come back to land use and zoning. If you can only build houses in small sections of your city, you’re setting yourself up for scarcity. The legacy of that continues today.”

1925: BUILDING BOOM

Back in the 1920s, though, the map still had plenty of untapped space as the city expanded to East Sacramento, then a new suburb. Developers Charles Wright and Howard Kimbrough create a large, tree-lined, villa-filled subdivision at the time called Tract 24, and would later be known as the Fabulous Forties. Sacramento’s population surged by over 50 percent in the Roaring ’20s, from 91,000 in 1920 to 142,000 in 1930.

Related: Is taller, denser housing near transit hubs right for the Capital Region?

Related: Opinion- Lawmakers Must Focus on Alleviating California’s Housing Crisis

1929: STOCK MARKET CRASH

Sacramento enters the Great Depression. By 1932, 27,000 of the county’s 140,000 residents were out of work. A winter storm destroyed crops of citrus fruits, forcing canneries, a primary employer, to drop employee compensation to 20 cents per hour. (For perspective, at the time, the average plumber earned $1.45 per hour.) The housing market freezes. Construction stops. Mortgages go unpaid; by 1933, half of all Americans were behind on their payments. Thousands of Sacramento residents, now homeless, gathered in shantytowns like Shooksville (near the city incinerator) and a muddy area near 20th Street called the Rattlesnake District. Many of the old Victorian mansions — now an unrealistic luxury — were split into apartments. “Families would make some extra money from boarders,” says Burg. “It was the mid-20th century Airbnb.”

1932: CONGRESS PASSES THE GLASS-STEAGALL ACT

The law forbid commercial banks from dabbling in the investment banking business, which many believed contributed to the 1929 crash. (As the saying goes, “Those who don’t remember history are doomed to repeat it.”)

1934: FDR SIGNS THE NATIONAL HOUSING ACT

Desperate to pump life into the economy, President Franklin D. Roosevelt creates the Federal Housing Administration, which overhauls the mortgage system and makes it easier for Americans to buy homes. Prior to the FHA, homebuyers would typically need a whopping 50 percent down payment and to pay back the loan in five years. Thanks to the new federally backed insurance, banks began lending with the now customary 20 percent down, 30-year terms that would help fuel decades of home ownership.

Yet, the growth came with a catch. When determining whether they should grant a loan, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (newly created by Congress) used color-coded maps to assess a neighborhood’s risk levels. The nominal logic: A riskier neighborhood is a riskier loan. They created four categories. The top one, colored green on the map, was for neighborhoods that were “new, homogenous, and in demand in good times and bad.” These were the homes of “American business and professional men.” The worst category was red. These neighborhoods were deemed “hazardous” that had an “undesirable population.” They tended to be black neighborhoods, and thus the era of denying loans to minorities through “redlining” began. “The federal government played a big role in racial discrimination,” says Garcia. “There were conscious decisions made to exclude and segregate certain populations.”

1942-45: WAR!

McClellan Air Force Base, circa 1965. (photo courtesy: Center for

Sacramento History)

As the nation mobilized to fight Hitler, the military poured money into McClellan Air Force Base and the Signal Depot, leading to more jobs, more houses and what would become Northern California’s second gold rush. “Building booms after World War II,” says Garcia. “There was so much demand after the soldiers came home.”

1949: PRESIDENT HARRY TRUMAN SIGNS THE HOUSING ACT OF 1949

All of those returning soldiers needed homes, and there weren’t

enough. “The housing shortage continues to be acute,” declared

Harry Truman in a State of the Union address. On the surface, the

act’s goal was to create 1 million units of public housing and

provide “a decent home and suitable living environment for every

American family.” Yet, like FDR’s earlier housing legislation, it

didn’t really help “every” American. An amendment was introduced

to explicitly ban racial discrimination; it was

voted down.

1956: EISENHOWER SIGNS THE NATIONAL INTERSTATE AND DEFENSE HIGHWAYS ACT

The city continues to push outward. Federal funding for highways — notably Interstate 5 and Highway 50 — means more growth, more suburbs and more houses. “Anything that expands transportation is huge for the region,” says Ryan Lundquist, author of Sacramento Appraisal Blog (and Comstock’s contributor). “This paves the way for more housing units.”

Highway 50 at Howe Avenue and Power Inn Road, taken in

1969.(photo courtesy: Center for Sacramento History)

1961: THE SPACE RACE BEGINS

To help put a man on the moon, Aerojet (which launched its Rancho Cordova plant in 1953) roars to life. The residential needs of Aerojet employees led to 12,000 new homes in a single year.

1970: GOV. RONALD REAGAN SIGNS THE CALIFORNIA ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY ACT

Smog clings to Los Angeles. Citizens complain of water pollution. On the heels of the National Environmental Policy Act (signed by President Richard Nixon on Jan. 1, 1970), CEQA requires local agencies to conduct detailed, specific environmental reviews of new housing developments. If the project is deemed to have a material environmental impact, then the developer needs to complete an environmental impact report. Nearly 50 years later, CEQA continues to polarize. Critics say the law has led to higher construction costs, fewer new developments and frustrating delays of the projects that do move forward. A review from the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office found that “local agencies took, on average, around two and a half years to approve housing projects that required an EIR.”

1970s: RAPID EXPANSION, SOARING PRICES

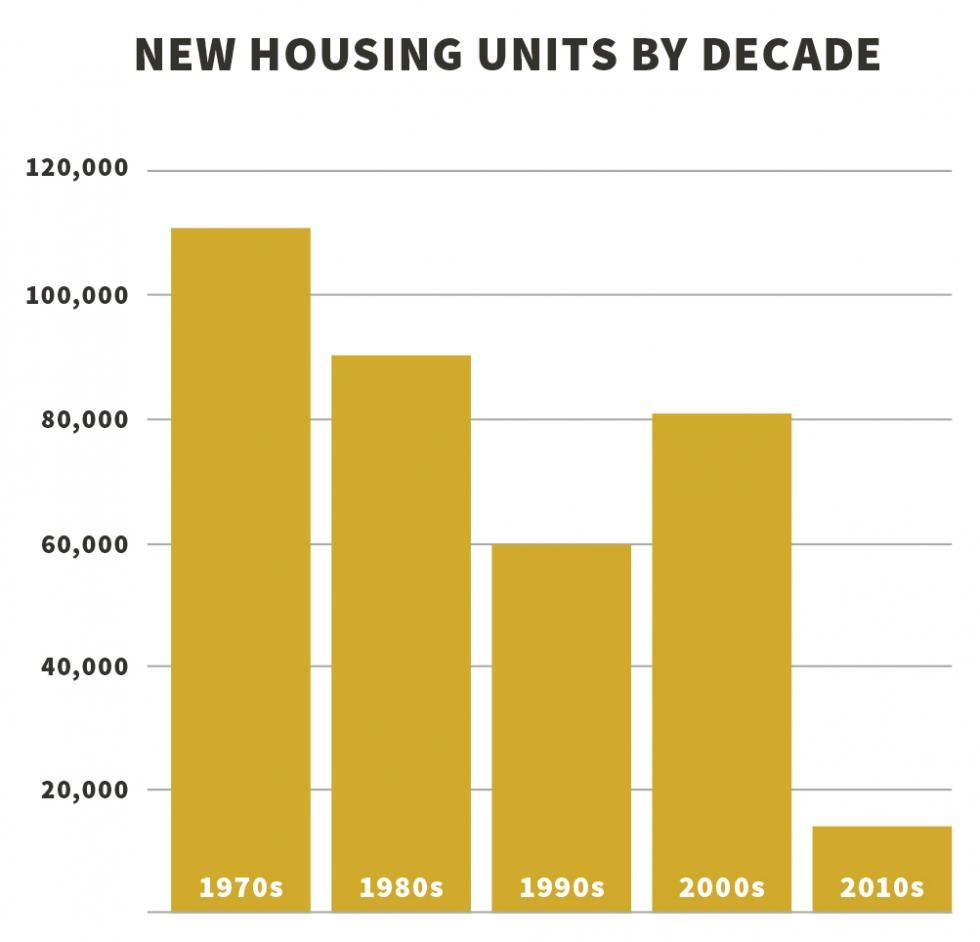

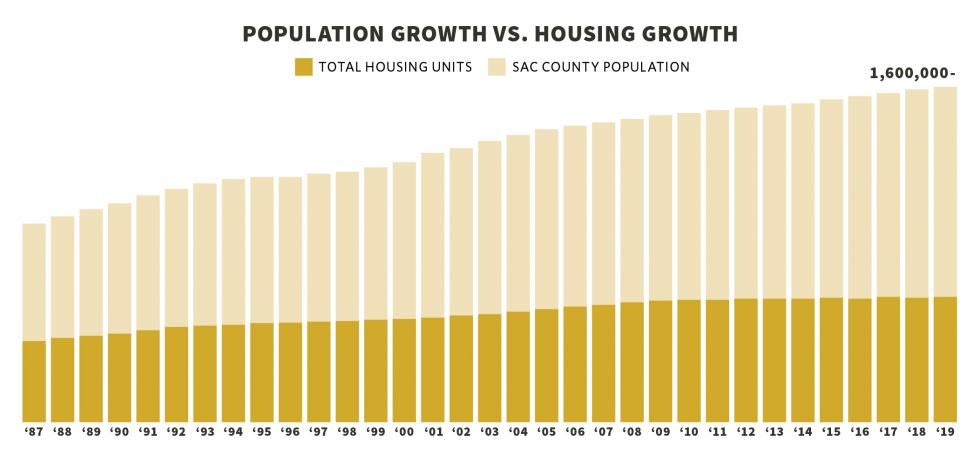

As the suburbs continued to sprawl outward — Roseville, Rancho Cordova, South Sacramento and Elk Grove — homes are built at a madcap pace. In 1970, Sacramento had a total of 212,000 housing units. The decade cranked out over 110,000 new units (53 percent of them single-family homes), a larger expansion than the region would see in the ’80s (91,000), ’90s (60,000), 2000s (81,000) and especially this decade so far (a meager 14,000). They were also pricier. Between 1967 and 1980, the price of the average home had more than tripled, up 350 percent.

1972: NEW ‘POPULARLY PRICED’ HOMES

Middle-class homes in the Larchmont Foothills sell for between

$19,450 and $22,300, according to the North State Building

Industry Association.

1978: PROPOSITION 13

“The most important thing in this country is not the school system, nor the police department nor the fire department,” said tax activist Howard Jarvis, after his Proposition 13 was amended to the California Constitution. “The right to have property in this country, the right to have a home in this country, that’s important.” Jarvis’ initiative passed in a landslide, hauling in 65 percent of the vote. The law, technically called the People’s Initiative to Limit Property Taxation, famously (or infamously) fixed property taxes at 1 percent of the home’s purchase price, and capped the annual increases at 2 percent.

While popular, its long-term effects are complicated and endlessly debated. Some say that government officials are now incentivized to approve commercial development deals instead of residential — as commercial developments could rake in more tax revenue. Then again, looking back, the NSBIA recently said that in the late ’70s, “with new mortgage programs and tax benefits of Prop. 13, the total amount needed to qualify for an ‘average-priced’ home is $1,800.”

1980: INTEREST RATES HIT HISTORIC HIGH, 20 PERCENT

Stagflation chokes the economy. Construction plummets. In 1979, there were 13,900 new homes; in 1980, half that. “The plight of the real estate industry during 1980 has been well-documented, with record high interest rates and rising housing prices eliminating more than half of all Americans from qualifying down payment and mortgage requirements,” explains an analysis from the Business Services Bureau, written in 1981. “Sacramento has been no haven for the suffering residential real-estate and construction industries.”

1982: GARN-ST GERMAIN DEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS ACT

Mike Gobbi has been a Sacramento real-estate broker for nearly four decades, with more than a thousand sales under his belt. He remembers that in the early ’80s, thanks to some lax loan regulations, it was cartoonishly easy to quality for a loan to purchase an existing home. “We called it the mirror test. If you could fog a mirror, you could buy a house,” Gobbi says. In 1982, the Garn Act tightened those restrictions, making it tougher to qualify for a pre-existing loan (of used houses), which nudged consumers toward new construction.

Thanks to a combination of Garn, lower interest rates and an improving economy, the market recovered — from 3,000 new homes in ’83 to 14,700 in ’87.

Related: Can fee adjustments incentivize more affordable housing projects?

Related: Housing crunch in Truckee and north Tahoe leaves workers with a long commute home

1990: SADDAM HUSSEIN INVADES KUWAIT

“I remember exactly when things started to change,” remembers Gobbi. He looked at his paper reports — this was pre-computer — and stared at the charts. “It was the weirdest thing. When the Gulf War started, I looked at the monthly chart and saw that inventory increased and sales went backward. Consumer confidence just went through the floor.” Gobbi says that he doesn’t blame the ’90s housing slump completely on the Gulf War, but “this was the emotional issue that started the turn.” While prices remained about the same (around $230,000), in the weak economy, the ’90s would see the number of new units plunge from 12,000 in 1990 to 1,700 in 1998.

1995: COSTA HAWKINS RENTAL HOUSING ACT

As voters in the recent midterm election remember all too well, Costa Hawkins limits the ability of the city to impose rent control laws (which would set a ceiling on how high landlords can hike the rent each year). Many builders insist that the housing crisis would be even worse without Costa Hawkins, citing Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck who quipped, “In many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city — except for bombing.”

1999: REPEAL OF THE GLASS-STEAGALL ACT

To spur financial “innovation,” the Depression-era banking regulations were repealed. Banks were now free to make dicey loans and bundle them into the toxic financial instruments that are widely seen to have led to the financial collapse. “The banks took advantage, and they started pumping out the loans and not thinking about consequences,” says Gobbi. “They could sell houses to just about anybody. If they could process the loan, they got paid, and they made money. The ‘greed factor’ steps in. It’s human nature.”

Just as sugar can give you a burst of energy before a crash, the easy lending led to more new homes. From 2000 to 2006, Sacramento built 68,600 new homes (an annual average of nearly 10,000), compared to 1,700 in ’98. Accelerating the growth: reverse redlining. “There were groups of people that for thE longest time couldn’t get credit, based on racial factors,” says Garcia. “There was a concerted effort to start extending credit to these people, but done in a predatory way.” The predatory loans often had balloon interest payments that could result in foreclosure or bankruptcy. “This was the genesis of the most recent recession,” says Garcia.

2006: ELK GROVE FORECLOSURES

“July 2006 was the last month in which we saw the upward movement in pricing,” remembers Dave Tanner, CEO of Sacramento Association of Realtors. “By August, sales had dropped off.” He says that Elk Grove, Folsom, Rancho Cordova and Natomas were especially punished, as they had the most new construction. “The stuff under construction died as buyers just walked away,” says Tanner. “In Elk Grove, where I live, there were houses that ended up being foreclosed.” When he saw these foreclosures, he knew things would get ugly. And they did. Home prices plunged from $370,000 in 2006 to $166,000 in 2011, and the number of new units dropped from 11,000 in 2006 to a historic low of 1,041 in 2011.

2008: FED SLASHES RATE TO HISTORIC LOW

On Dec. 8, the Federal Reserve pegs the interest rate at 0.25 percent, the lowest in history, and they would get even lower in 2012. This decade of low rates has consequences. Lundquist says that consumers have gotten used to these historically low rates, and now, in 2019, as they begin to inch up, it can feel like sticker shock. “Lack of new construction is the biggest issue of the housing shortage, but with such low rates, this creates a situation where there’s less incentive to move on from their present home.”

2008-10: LABOR FLEES

“Before we had the downturn in 2006, we were moving forward with a lot of construction,” Tanner says. “And when the construction stopped, a lot of the labor left the market — particularly to Texas and Arizona.” The shortage is being felt across the board — in 2016, the North State BIA launched a concentrated initiative to train up 5,000 workers in five years.

2014: MORE MIGRATION FROM THE BAY AREA

Think Sacramento housing prices are high? Look at San

Francisco. The median Sacramento price jumped from the low of

$180,000 in 2009 to $370,000 in 2018 — more than double — yet San

Francisco soared from $392,000 in 2009 to $970,000 in 2018. This

impacts prices here at home. “I can’t tell you how many people

I’ve worked with in the past year that sold their cracker box for

$1.5 million, and bought five times the house for half the

money,” says Gobbi. Real-estate website Redfin reported that in

October through December 2017, there were 15,000 users of their

site (home searchers) living in San Francisco who wanted to

leave, and their top destination was Sacramento.

2016: HISTORIC LOWS FOR NEW HOUSING

From 2011 to 2016, each year averaged only 1,400 new housing units — by far the lowest stretch in the last 50 years, and possibly ever though definitely since 1965 — based on data from the Sacramento Area Council of Governments and the 1981 Business Services Bureau. “This shortfall has been accumulating for about 10 years now,” says Tanner. “Valuation is driven by supply and demand. And California doesn’t have the supply.”

2017: PRICES LEAPFROG INCOMES

Tanner likes to keep in mind the big picture. “What routinely happens in the real estate industry is that the price of houses accelerates at a rate significantly greater than the acceleration of income,” he says, until the prices get so high that they’re out of reach for most of the population. This occurs over and over again.” To his point, from 2008 to 2017, the median home price in Sacramento County has jumped 59 percent. Median income? Just 11 percent ($57,000 to $63,000).

2018: PROP. 10 REJECTED

In the November midterm election, voters reject the initiative that would have repealed Costa Hawkins, adding to the frustration of renters. The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Sacramento is now $1,360, over double what it was in 2011 ($668), according to the rental website Rentjungle.com.

Tanner sees reason for optimism: “It’s encouraging to see more new construction starting up,” says Tanner, who sees growth in Elk Grove and Folsom. “I think the Sacramento housing market looks good for the the next several years. It will likely flatten out for a while with higher interest rates, but will then move up as incomes catch up.”

For perspective, we can again turn to the Business Services Bureau, which observed that “the increasing demand for rental units from the growing population, the increasing unaffordability of homeownership, and the low incidence of new rental complex construction will strain the existing rental housing stock and lead to record low vacancy rates unless these problems are alleviated.”

Very true. Yet these words were written not this month, or this year, or this decade, but in 1981. The housing challenge is real and it’s complicated, but it’s also part of a grand history of ups and downs and booms and busts. Just ask the squatters.

Comments

Unfortunately, the racial bias is still prevalent in both rentals and sales. I think that is the only aspect missing from this otherwise great review!

I'm relatively new to the area and I found this piece very insightful. Thank you for this piece.