It’s late on a Monday evening. West Sacramento Mayor Christopher Cabaldon sits on his living room sofa, at the center of a large space void of clutter. He has remained here for the past two hours, rehashing details of his private life: his inclination toward isolation, his coming out story and, most significantly, memories of his mother’s fatal accident. As the sun slips below the horizon, Cabaldon neglects to flip on a light switch. Nightfall dims the room, and as the mayor goes on about the tragic roots of his remarkable enterprise, he allows his room to fill with darkness.

Major Area of Focus: YOUTH EDUCATION

Kids’ Home Run: During his 2013 State of the City address, Cabaldon announced FutureReady, an initiative to improve the lives of young people in West Sacramento through civic engagement, college and career readiness, and work-based learning. In 2017, Cabaldon (who works in education advocacy for his day job) took his focus on the well-being of children even further, and announced Kids’ Home Run, an educational and jobs initiative for youth ages 4 to 18. The initiative includes universal preschool, access to a college savings account for kindergarteners (both locally-subsidized), paid internships for high school students and free tuition for high school graduates who enroll in a local community college.

In his professional role, Cabaldon is usually an exceptionally fast talker. Few can match his cadence, especially when he’s revved up on a political issue on which he wants to lead. He’s won six re-elections to become the longest-serving mayor in West Sacramento history, a tenure marked by undeniable progress. Under Cabaldon’s watch, the city has transformed from an impoverished industrial district in Yolo County to a modernizing area with trendy riverfront residences and communal spaces, a minor league baseball team, and a sustaining industry around food and agriculture. While scattered blight remains throughout the city, Cabaldon has shepherded progressive programs like bike-sharing, urban farming and locally-subsidized preschool.

Given those accolades, a fast, confident speaking rhythm is unsurprising. But when faced with intimate questions about the violent death of his mother during his childhood, or about hiding his sexual orientation until age 41, the pace of Cabaldon’s words slow down. The volume dips. What was vibrant and verbose becomes soft and hesitant. His speech is only part of it. A visible change occurs, too.

Since he was an adolescent in Los Angeles, Cabaldon says he has always enjoyed being known as “the smart one, the driven one and the one who gets things done.” He appears completely at ease with public speaking and boasts that his speeches are never written or rehearsed. Cabaldon’s involvement in a national mayor’s group has granted him access to Congressional leaders and the White House. He also works as a partner at Capitol Impact, an education advocacy group, and has sat on multiple nonprofit boards and public commissions.

When Cabaldon returns home each night, he shuts the door behind him and continues to work. When he isn’t working, his focus shifts inward. The mayor, who turns 52 this month, enjoys solitude — at times to the point of being reclusive. As a boy, Cabaldon would spend hours in his room alone. As an adult, the mayor has never fallen in love, had a long-term partner or even a short-term boyfriend. But through his entire adult life, he continues to share each personal milestone with his mother, Diane.

Cabaldon leaves town a few times a year to travel over 360 miles south to the San Fernando Mission Catholic Cemetery in Mission Hills. He speaks aloud to Diane while standing over her tombstone, sharing with her his deepest thoughts. He considers what advice she would offer. In 2000, six years before he very publicly came out of the closet, it was Diane to whom he said, for the first time in his life, the words, “I’m gay.” Though the mayor characterizes these meetings as uplifting, he says he typically walks away in tears.

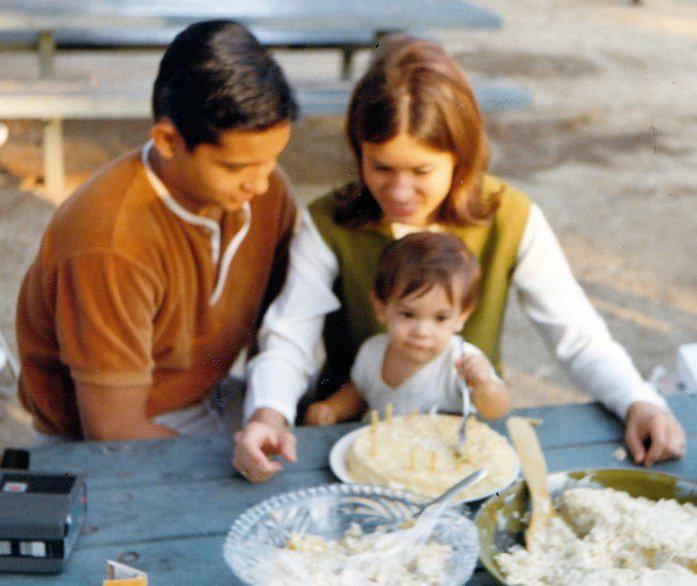

West Sacramento Mayor Christopher Cabaldon on his first birthday,

with his mother Diane and father Larry. photo: courtesy of

Christopher Cabaldon

When Diane died in 1979, Cabaldon was just 12 years old, sitting in the backseat as his mother’s BMW smashed into a guardrail off Victory Boulevard in North Hollywood. She is buried in a family plot, eight miles from the scene of the accident.

When first asked about the details of his mother’s death, Cabaldon backtracks a few months and conjures the image of a Betty Crocker cherry chip birthday cake with unsweetened whipped cream frosting. Diane had baked her eldest son’s favorite cake for his twelfth birthday and placed it atop a plastic, imitation-crystal cake tray. Before cutting the cake, Cabaldon insisted that he, his mother and 9-year-old brother Dylan wait for Larry, their father, to return home.

The family of four lived in the upscale Hollywood Hills neighborhood, in a spacious home Cabaldon says his parents barely afforded. Diane, a university professor, had grown up in a blue-collar family in Michigan as the daughter of Czech factory workers, and moved to California as a teenager to study economics at Cal State Northridge, where she met Larry.

Larry was a second-generation Filipino immigrant — his parents worked at a soda fountain in the Central Valley, and Larry’s father ran a secret gambling ring under the store. Through Cabaldon’s early childhood, Larry worked as a corporate headhunter. He now operates a consultancy firm for businesses and has authored a book titled, “God in the Boardroom: Why is Christianity losing market share?”

But on that night in November, Larry didn’t arrive home. As the hours passed, Diane grew distressed. After Dylan went to bed, Diane inexplicably gave Cabaldon the “birds and bees” talk. He remembers being repulsed by the thought of human reproduction, later equating sex with his mother’s aggrieved state of mind and distancing himself from both.

The next thing Cabaldon remembers is the sound of himself screaming.

Past his bedtime, Cabaldon eventually crawled under his covers and fell asleep with the untouched cake still sitting in the kitchen. He awoke to the sound of crashing glass and screaming, and crept down the hallway to investigate. Diane was in hysterics, throwing things in the kitchen. Larry still wasn’t home. The front door stood open. The cake was smashed to bits on the front porch.

Two days later, Diane and Larry summoned their two sons and announced the couple was divorcing. Larry would immediately move out while Diane looked for a new home for herself and the boys. Neither parent mentioned that Larry had met another woman, a cocktail waitress who would move into the family’s home shortly after Diane’s death.

On a Friday night the following April, Diane drove her sons to the house of her sister, Janice Tully, to celebrate Tully’s daughter’s birthday. Wine flowed freely, Hall & Oates played on the stereo and the kids played games. Cabaldon recalls his mother acting upset — a common sight following the breakup — and finishing several drinks. After the party, the two boys piled in the back of the car and Cabaldon immediately fell asleep. After Diane pulled away, Tully noticed Diane had forgotten her purse.

The accident occurred with the BMW traveling back toward Tully’s house. Diane drove the wrong way up an off-ramp on Highway 170 and crashed into a guardrail. Tully heard the news in a late-night phone call and rushed to the hospital. “It was a horrifying sight,” Tully recalls. Diane “was hooked up to all these machines that were keeping her going. [The doctor] said she was basically braindead.”

Cabaldon remembers getting into the car and then waking up covered in bandages in a hospital bed in Glendale. His ankle and arm were wrapped, and he had a cut along his face. In the next bed over, his brother Dylan was also heavily bandaged. Larry entered the room.

“Boys, there was an accident,” Cabaldon recalls his father saying. “You were in a car accident, and your mom didn’t make it.”

Major Areas of Focus: THE RIVERFRONT

Raley Field: On May 15, 2000, West Sacramento unveiled its new $46.5 million stadium, during opening day for the Sacramento River Cats minor league baseball team. The stadium’s construction — on the site of old warehouses and railyards — was financed using bonds repaid through ticket, concession, advertising and other revenues, and not taxes, much to the satisfaction of residents. Over the past 17 years, the stadium has hosted hundreds of baseball games, along with soccer matches, concerts, fundraisers and other events. Raley Field’s success played a major role in spurring the development of the CalSTRS building, riverfront housing and The Barn venue — all located near or within the trendy Bridge District.

The next thing Cabaldon remembers is the sound of himself screaming.

Tully says Cabaldon barely uttered a word at the funeral. He didn’t cry; he just stared blankly ahead with his arm in a cast. Cabaldon says his isolation grew over the following weeks, months and years. He seldom left his room. Sometimes he sought refuge in the darkness of the bedroom closet. Other times, he dragged in couch cushions, shut the door and built a fort to hide in.

“My room was not enough. I had to be inside this closet,” Cabaldon says, recalling the period. He adds, “If I could have just called up Postmates and had someone come over and execute me painlessly, I wouldn’t be here today.”

Cabaldon would sometimes play with X-men action figures in his room — but instead of fighting with fists and super powers, his X-men formed superhuman government committees and delivered floor speeches concerning mutant policy. The play sessions marked the first musings of a child naturally drawn to politics, but took on a greater significance after Diane’s death. Government, with its laws, customs and protocol, offered structure to a life that Cabaldon viewed as pointless.

“Under no set of regular rules would you take someone’s mom away at that age for no reason,” he says. “This was a way to reassert some sense of order.”

Cabaldon attended the first magnet school in Los Angeles, the Center for Enriched Studies, at the behest of his mother because the campus represented the cornerstone of a racial integration effort by the school district. But Cabaldon’s enrollment, a political action pressed by his mother, left him geographically distanced from his classmates. Gar Russell, a childhood friend, remembers long phone conversations that would end with Cabaldon upset when Russell said he had to get off the call.

The two also participated together in Junior State of America, a student-led debate and mock government organization. “He liked order,” Russell says. “He was friendly and outgoing, but at the same time had a reserved quality about him. I’d say it was looking out for himself and trying to protect himself.”

Cabaldon moved to Sacramento in 1987 after graduating from UC Berkeley with an economics degree, the same subject taught by his mother. Armed with an inexhaustible work ethic, Cabaldon quickly rose the ranks as a State Capitol staffer. After a few years, he was appointed chief consultant of the Assembly Higher Education Committee.

That same year that Cabaldon moved to Sacramento, the voters of West Sacramento took a pioneering leap by approving cityhood. The previous three decades had seen a slow deterioration of West Sacramento’s primary neighborhoods — Bryte, Broderick and the one with the city’s namesake — as well as their shared crown jewel, West Capitol Avenue.

Cabaldon’s involvement in a National Mayor’s group had granted

him access to congressional leaders and the white house.

Christopher Cabaldon with then-President Barack Obama in late

2015. photo: courtesy of Christopher Cabaldon

The main drag of West Sacramento was an erstwhile gem, formerly frequented by anyone traveling east from San Francisco. According to local lore, President Eisenhower and Clark Gable stayed along the storied motel row. But after World War II, the completion of the four-lane Interstate 80 bisected the former Highway 40 that shuttled travelers down West Capitol Avenue, and the former glitzy drag slowly became the domain of drifters and prostitutes.

The incorporation of cityhood was largely a referendum on the blight of West Capitol Avenue, a symbol of the entire area’s dilapidation. Food and shopping options were virtually nonexistent in “East Yolo,” as the locals called it. Crime rates were high, the roads were pocked with potholes and water quality was poor.

Cabaldon moved to West Sacramento in 1993 and embraced the blue-collar community as a modern-day Mayberry, the fictional working-class paradise of “The Andy Griffith Show.” Outside of work, Cabaldon admits he had “nothing going on in life.” He stopped dating women in his mid-20s and barricaded his innermost feelings from friends. Not only did the young politico abstain from social drinking for fear of an embarrassing disclosure, he barely looked people in the eye in order to conceal his two “dark secrets” — an enduring grief for Mom, and a jumble of alienating thoughts and insecurities stemming from what he would later recognize as homosexuality.

Though Cabaldon’s professional passions were directed in state and federal policymaking (he envisioned someday working in Congress), he regarded local government as a worthwhile endeavor and potential stepping stone. But the notion of running for public office caused him concern.

Major Area of Focus: FOOD & AGRICULTURE

Urban Farm Program: As other cities in the Capital Region spent time, energy and headaches to develop urban agriculture ordinances to appease a growing demand among residents, the City of West Sacramento took a different approach: It approved an urban farm without an ordinance. No problems arose. The City’s leadership soon led to a partnership with the Center for Land-Based Learning and the creation of the West Sacramento Urban Farm Program, which converts vacant lots into farm business incubators, and provides a training ground for small-scale beginning farmers. More than 600 volunteers work on these farms annually, growing over 25,000 pounds of produce per month during peak seasons.

“I felt so unlike regular people in the world, but particularly here in West Sacramento, that the idea of being a politician — just the idea of putting yourself out there and having people ask questions about you and wondering about your personal life and all that — was something I wasn’t up for,” he says. “But I felt like something had to get done.”

Voters elected Cabaldon to the West Sacramento City Council in 1996, and the Council appointed him mayor two years later. He was elected mayor by voters in 2004 and has been re-elected every two years since.

“He’s an introverted brainiac.” Mike McGowan, former mayor, West Sacramento

One of Cabaldon’s early projects was helping design the Southport neighborhood as one of the region’s first walkable communities that followed a nascent smart-growth movement. Local leaders constructed Southport to house both industrial workers and company executives, a move that generated the city’s first influx of wealthy residents.

Also in the late 1990s, Cabaldon helped create the financing plan for Raley Field, which attracted even more affluent residents from across the Sacramento River. The year 2004 saw the opening of the Southport Town Center, anchored by Nugget Market and ultimately drawing Ikea to town. Public officials used the increased tax revenue to improve city services and infrastructure, building a new City Hall and community college complex on West Capitol Avenue.

“He spends a lot of his time studying. He’s an introverted brainiac,” says Mike McGowan, West Sacramento’s first mayor and a longtime colleague of Cabaldon. The mayor is a gifted public speaker, McGowan adds. “But take him off the podium and have him walk around and talk to people. You can see that’s not his comfort zone.”

Cabaldon says concealing his sexual orientation for most of his adult life prevented him from building deep, emotional connections with anyone. For years, he says, he avoided eye contact with people (almost unfathomable for a career politician). That neurosis, combined with a natural preference for solitude, freed up nights and weekends and drove him to a life of near-constant work.

Major Area of Focus: TECHNOLOGY IN GOVERNMENT

Code for America: West Sacramento was one of seven cities nationwide to participate in the 2015 Code for America fellowship program, which connects fellows with local government to better utilize technology to tackle a community’s pressing issues. In West Sacramento, those issues involved health care and food access. The San Francisco-based Code for America is a nonprofit organization that aims to make government services simple, effective and easy to use. Under Cabaldon’s leadership, West Sacramento has been at the forefront of using technology in government. The City, for instance, has worked with companies to develop or test mobile apps or online tools to improve services, such as permitting processes for developers and addressing homelessness.

“Can you imagine if you had no time or bandwidth for emotional distraction of any kind — not just involvement, but even thinking about it — what you could do with your career? I don’t know what I’m giving up, but I know what I have, so I’m just charging toward this thing,” he says.

As a child, Cabaldon remembers family holidays, sitting around the chips and the Coors, and hearing his father and uncles say things like, “If I had a gay son I would be the first one to shoot him,” he says.

“The fact that I’m telling you that now, 40 years later, it definitely sunk in,” Cabaldon adds.

Cabaldon says he truly realized he was gay in his mid-20s, but coming out of the closet did not seem like an option. He didn’t know any gay politicians, and all the gay characters in movies and television were “super-liberated caricatures.”

In 2000, Cabaldon stood over Diane’s tombstone, and with tears streaming down his cheeks, made the most powerful declaration of his personal life.

“I’m not sure I’m getting this right, Mom. I’m trying to do the right thing. I think I figured this out,” he remembers saying. The following revelation began deflating a capsule of pain born many years before: “I think I’m gay,” Cabaldon told his mother.

She probably already knows, he reassured himself. Even if the news would have disturbed Diane when she was a conservative 32-year-old, society had since become more understanding, and Cabaldon assumed his mom would have evolved too.

“Because I’m achievement-oriented I’d think, ‘She’d be OK with this because I’ve done this and this,’” the mayor recalls thinking at the time. “She would have to be happy with all these other things.” (Cabaldon came out to his father in 2004. The two men seldom speak.)

In 2006, Cabaldon saw a casting call for a reality show called “Coming Out Stories,” which chronicled gay people as they prepared and eventually came out to friends and family. If a politician would just go on this show, attitudes would shift and I could be openly gay, Cabaldon remembers thinking.

“I have definitely felt more human, and a better human.” Christopher Cabaldon, Mayor, West Sacramento

The mayor poured his heart into a two-page letter to the show’s producers, describing the casual bigotry encountered by a closeted politician in a working-class town, and the fear of being outed. Cabaldon explained that he was considering coming out at his State of the City address, his most prominent annual address. The next day, the New York-producers asked the mayor if they could send a film crew out to live with him, and film him each day leading up to the announcement. He agreed.

The response to Cabaldon’s coming out speech was overwhelmingly positive. Hundreds of strangers from across the country wrote the mayor letters about painful struggles they had endured as members of the LGBT community. An Elk Grove navy officer told Cabaldon he couldn’t come out for fear of losing his job, “but pretty much all my close friends know,” he wrote. A West Sacramento municipal worker spoke of the loneliness he felt thinking he was the only gay worker at City Hall. Another wrote to say Cabaldon’s story inspired him to come out to coworkers by bringing his longtime partner to an upcoming company holiday party.

The mayor said the flood of emails enabled him to finally break free from a “hermetically-concealed room [of the mind] that no one else could possibly get into or I could get out of,” he says. That sense of liberation, he adds, hasn’t subsided in over a decade.

“People tell me more things than they used to. They show me more things than they used to,” Cabaldon says. “I have definitely felt more human, and a better human.”

To this day, the mayor remains regimented about when and where he allows himself to feel sadness. He maintains a compartment in his mind for emotional pain, accessible through a portal that can be shut as decisively as it can be opened.

“From the moment of my mom’s passing, all emotions can be wrapped into that one space for me; all pain and sadness and loss,” he says. “I go there when I’m ready to let myself feel … a place where I know I can come out of.”

Back in his living room, Cabaldon makes no effort to fill the silence with small talk after the interview ends. He doesn’t pretend to enjoy talking about his mother’s death. He says he opened up due to a strongly-held belief that politicians — and people in general — should “be more authentic and share more than just their opinions.”

Alone again, he will later describe a stirring confrontation with the backwaters of his mind that requires a conscious effort to re-anchor himself as an adult. A journey back to different periods of life, each era more painful than the last, up to the searing moment of Diane’s death, is not a safe path for him. Being probed about these memories is a “basic violation of the security of the metaphorical couch-pillow-fort that I built” many years ago, he says. That scared boy never found resolution. He just matured into something else.

At some point, West Sacramento began to mature with him. Outside his window, Cabaldon can watch the nightly fireworks display above a baseball stadium he helped bring to town. He can walk outside his upscale condominium for which he helped lay the groundwork, and down the waterfront district he helped engineer. The mayor has worked feverishly for decades to show Diane that something good would, and has, stemmed from her fatal accident. He tells himself that she is listening, though he doesn’t truly believe it.

And yet, “Diane would be so proud of him — beyond the moon and into infinity,” says Tully, Diane’s sister. “I can’t imagine how proud of him she would have been.”

Comments

This was truly a long read. It wasn’t boring and I kept scrolling down to read more. I think writer Allen Young did a great job of allowing a avid reader, a visitor to the Comstock mag website and local Sacramento resident that frequents West Sacramento insight to who Mayor Cabaldon is.

Great article about a great man doing great work.

This was truly a long read. It wasn’t boring and I kept scrolling down to read more. I think writer Allen Young did a great job of allowing a avid reader, a visitor to the Comstock mag website and local Sacramento resident that frequents West Sacramento insight to who Mayor Cabaldon is.

Great article about a great man doing great work.

I've met Christopher a few times. The first was when he presented me the award for Wet Sacramento most improved residence beautification many years ago.(This unfortunately has been discontinued.) I have always found him to be an interesting. eloquent and handsome man. I moved here from Elk Grove and absolutely love it here. I appreciate the police presence. What a great story, Allen. It is also inspiring.

I've lived in West Sacramento for many years, during the early years as the Mayor, a local school had students hand out candy canes and collect food for the less fortunate during the Christmas season. Following Santa on the fire truck in the exchange. I was an assistant cheerleading coach and help supervise students. Mayor Cabaldon walked along side the students, handing out candy canes and taking collections for the less fortunate. In the fire truck my son with Brain Cancer got to ride along with the firefighters in the truck. I just couldn't stop thinking about how as a Mayor he walked miles interacting with his constituents and being so humble and kind. Throughout the years I've watched his vision for this community make leaps and bounds. We now have a community center, Sacramento City College extension classes for residents and many more businesses move here or start up. That night watching my son have a wish come true and with the Mayor walking along with everyone was a memorable moment. I hope Christopher understands deep in his heart a mother is not meant to watch their children go before them. She's watching over you. Your Angel and biggest cheerleader. Always remember that you where left here on this earth to complete what your path is. We may never know the lives we've changed in uplifting ways, some are not for us to know. The people who's lives where made better will forever remember, and in turn do good for others. In reading this article you had many obstacles to overcome. Heartbreak and difficult decisions to share regarding your private life. By doing so someone facing some of the same decisions may now find a way to find the courage to also do so.

Beautiful story. West Sac is so fortunate to have this man, with all of his complexity. How wonderful that his healing is reflected in the progress of the community.

Mayor Cabaldon has been a hero not only to the LGBT community, but to people who strive to do genuine good in their communities. I've long looked up to the Mayor and look forward to seeing him do more for us all in the Sacramento-region!

What a nice profile. I worked with Christopher on community college issues when he staffed the Assembly Higher Education Committee and still own a condo in West Sacramento. He has been a great mayor and contributor to that community.

A great piece about a good man and great leader. He has helped a community in west sac but also thousands of students on his service to education.

Poignant piece about a complex subject. I, too, lost my father suddenly at age 13. You can see how a parent’s early death takes a toll on the child. So glad Mayor Cabaldon told his story to Allen Young who reported it so brilliantly. It will help others.

A very uplifting, inspirational well-written article about a great leader! Thank you @MayorCabaldon for your services and more importantly for following your path and sharing God’s gifts to your constituents.

Mayor Cabaldon's civic influence has gone far beyond West Sacramento. Many years ago, as a rookie council member recently appointed to the Sacramento Area Council of Governments board of directors, he proposed what staffers called the "Cabaldon Compromise," which led to every city in the six-county region being directly represented on that board. That was just the beginning of years of regional leadership in support of a sustainable region.

I knew Diane Cabaldon when we were both graduate students in economics at UCLA in 1967-1968. We had only one or two classes together, but I always remembered her because she was so bright and well-prepared. She was enthused about economics and could be animated in making a point. I have learned online that she became a very popular professor after she completed her Ph.D. I was shocked and saddened to learn of her death. The article helped me understand that tragedy. I wish I could know more about her life.

He's my boo and he's wonderful. =)