It was Rebecca Lee’s turn to climb the rope when the symptoms kicked in. She was in seventh grade at Kit Carson Middle School in Sacramento. The other kids in her P.E. class had climbed the rope. Gripping the rough, twisted fibers, Lee tried to climb, but pain seized her chest.

“I wasn’t able to pull myself even a little up,” Lee recalls. “I guess it was the pain that prevented me. The whole P.E. class was watching; a few kids laughed because I wasn’t able to pull myself up at all.”

Like her father, Lee was born with tetralogy of Fallot, or TOF, a combination of four congenital heart defects that affect the structure of the heart. As an infant, she had a shunt put in to get enough oxygen. When she was 6, the holes in her heart were patched up and the pulmonary valve widened. At age 16, the valve had to be widened again in her third open heart surgery. Her mom said she didn’t smile for three days after that one, she recalls. It hurt to laugh. Coming back to school, other kids recounted their fun vacations and trips to water parks. Lee kept her surgery to herself. She didn’t want to be a “downer.”

At age 52, Lee needed to replace the pulmonary valve. In the past, this would’ve entailed yet another grueling surgery. But thanks to a new FDA-approved device — the Edwards SAPIEN 3 transcatheter pulmonary valve system with a catheter-based stent — she was given a less invasive solution. Last November, at Sutter Medical Center, Sacramento, an interventional cardiologist successfully implanted the valve without opening her chest.

“A week later, I was able to go out to watch the tree lighting in Old Sacramento,” says Lee, a registered veterinary technician who cares for cats and dogs. “I could walk around, slowly, but I wouldn’t have been able to do that with open heart surgery.”

Lee’s story is a testament to resilience, revealing both her personal strength and the evolution of heart care over the past 40 years. Since 1950, heart disease has held the title as the leading cause of death for adults, with 695,000 people dying from it each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal heart disease in the U.S. had gone down significantly since 1990, but a recent Rutgers study notes the trend may reverse if Americans don’t quit smoking, drinking and overeating.

Dr. Daniel Cortez, director of Pediatric Electrophysiology at UC

Davis Health, has placed more than 40 leadless pacemakers, mostly

in the ventricle.

Lifestyle changes aside, advancements in heart care tools and technology have made surgery less invasive, reducing pain, hospital stays and overall recovery time. These innovations have not only improved patient outcomes, but have also led to greater recognition of hospitals in the region as high-quality heart care centers.

From Sutter Medical Center, Sacramento to Mercy General Hospital, part of the Dignity Health network, to UC Davis Medical Center and others, area hospitals have been earning marks of excellence for heart care.

Climbing higher

The Joint Commission is an independent, not-for-profit organization that evaluates and accredits more than 22,000 U.S. health care organizations and programs. According to Andrea Leigh Yates, the commission’s associate field director for Disease Specific Care, Sacramento’s health systems have a long and credible history regarding heart failure patients. “A certified health care organization in the Sacramento area was among the first to organize and protocolize outpatient care for chronic heart failure rather than treating it as an episodic inpatient disease,” Yates said in an email. “It set an example for the rest of the country to follow; that helped pave the way for some of the inroads that have been made in the overall management of heart failure today.”

Mercy General Hospital is home to the nationally recognized Heart & Vascular Institute with Joint Commission accredited programs that include Primary Stroke and Chest Pain with PCI (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention), among others. In 2021, after demonstrating consistent and quality care for heart attack cases, UC Davis Medical Center earned The Joint Commission’s Gold Seal of Approval and the American Heart Association’s Heart-Check mark for Primary Heart Attack Center Certification.

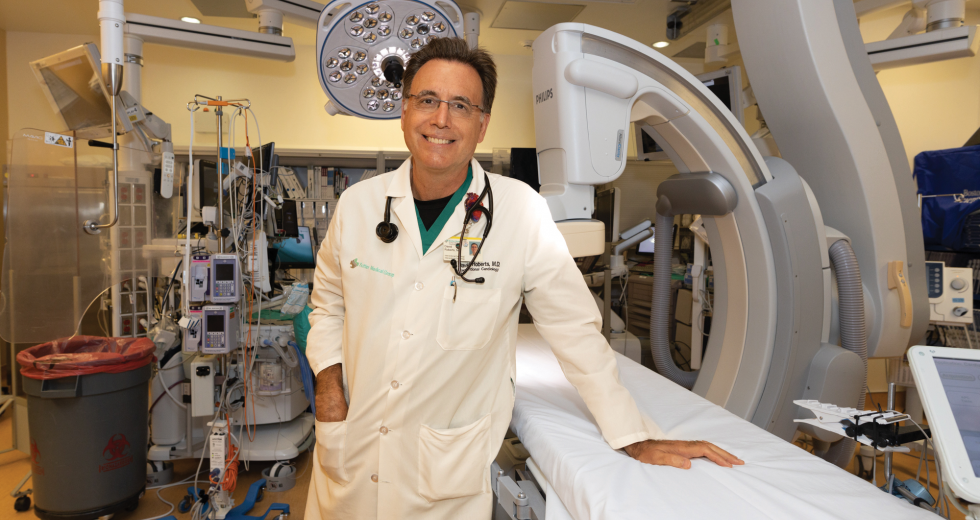

In April, Sutter Medical Center, Sacramento became only the second heart program in the West to earn The Joint Commission/American Heart Association Comprehensive Cardiac Center certification. Providing cardiac services since 1957, Sutter Medical Center, Sacramento received this award after a thorough, unannounced on-site review, which prompted workflow tweaks like more consistent order sets, among other things, according to Dr. David K. Roberts, medical director of the Sutter Heart & Vascular Institute.

“What we had to do is take a step back and look at the whole program and tie it all together,” he says. “The process actually made us better. It took us that next level up.”

Thirty years ago, Sacramento had an “image problem,” Roberts says, which made quality doctors seek better known programs elsewhere. But this has changed in the past three decades with accreditation and certifications making the region’s health systems more prestigious and appealing to top-tier health practitioners.

“Everyone talks a big game,” Roberts says. “When you have a certification like this, you’ve got that stamp from an independent outside source that says, ‘These guys are the real deal.’”

Health systems invest in various cardiac certifications to showcase their commitment to quality outcomes that meet or exceed regional and national standards, according to Nathanael White, division director for the Cardiovascular Service Line at the Northern California division of Dignity Health.

Before COVID, strategies of care were often limited by “rigid manual systems,” he says, which were clunky for both physicians and patients. For instance, patients faced a number of health system hurdles to get from general medical to see a doctor who specializes in advanced cardiac treatment options. Now, due to evolving priorities and higher demand for alternatives, the focus has shifted to streamlining patient care through telehealth, better screening for early diagnosis and minimally invasive procedures.

Over the next decade, White expects to see advances in two key areas: structural heart and cardiac electrophysiology. Structural heart care uses a “heart team” model, he explains, bringing together interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons and advanced imaging cardiologists. They evaluate patients and, depending on the severity of the case, would move forward with a procedure to deliver a new aortic heart valve without open heart or open chest surgery. Cardiac electrophysiology care focuses on the early diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias and related conditions. The goal here is to help minimize the debilitating symptoms patients can feel due to their erratic heartbeats.

According to White, Mercy General Hospital in Sacramento has taken the lead in improving patient care by using navigation teams and adjusting care strategies. Through better education and advanced technology — including mobile health apps, fitness trackers and heart rhythm monitors — patients and health care providers can identify symptoms, make faster referrals to specialized heart teams and tailor treatment plans to each patient. Kaiser Medical Centers and Marshall Medical Center in Placerville also have cardiology departments.

“Is your goal to go to your grandchild’s birthday party and be alive for a couple years, or is it to run a marathon?” White asks. “Then we customize the plan based on what the goals are, making sure we don’t lose sight of that just to count the number of procedures.”

Power of communication

At UC Davis Health, the treatment plan for 28-year-old Roberto Hernandez was not only customized, but cutting edge. He has dextrocardia, a rare congenital heart condition where the heart is in an abnormal position with a double outlet, pointing toward the right side of the chest instead of the left. Due to an infection, his pacemaker urgently needed to be replaced.

Dr. Daniel Cortez, director of Pediatric Electrophysiology at UC Davis Health, has placed more than 40 leadless pacemakers, mostly in the ventricle. But the heart procedure Hernandez needed had never been done before: two different types of leadless pacemakers in two different chambers of the heart.

Rebecca Lee was born with congenital heart defects which required

open heart surgery throughout her childhood. Last November, an

interventional cardiologist at Sutter Medical Center successfully

replaced her pulmonary valve without opening her chest.

During a prior lead extraction, the team removed the infected wiring and device and placed a temporary pacing device. The day before the main procedure, Cortez rehearsed deploying the catheter and demonstrating the pacemakers to “refresh my muscle memory,” he says. The morning of, he drank coffee and carrot juice for energy.

It was May 2023. In an electrophysiology lab, a sterile room filled with high-tech equipment, Cortez and his team used a catheter to place a new pacemaker at the top of Hernandez’s heart (in the atrium) and a second one at the bottom of his heart (in a ventricle). The two pacemakers talk to each other via “mechanical heart squeeze,” Cortez says. One drives the atrium, the other senses the mechanical contractions and drives the ventricle.

“He’s the first guy to ever get something like this: Two different pacemakers talking to each other,” Cortez says. “He would’ve had to live with an infected pacemaker and probably would have died from it.”

This new technology allows patients to pace all the time and get up to 20 years or more from the battery with a low infection risk, he adds. Two months later, Hernandez is adjusting, and he messages Cortez when he feels any discomfort.

“People like him and the team he put together deserve recognition,” Hernandez says. “I still have moments where I’m fighting with myself, trying to take deep breaths. … Whenever I have a question, communication between my doctors is really great.”

A positive outlook

Cardiac credentials for excellence represent a quality of care for both health care professionals and patients, but from different angles. Health practitioners take a broader view.

“What can your institution do in a more efficient way that leads to faster recovery for patients and less complications, and that makes you competitive and cutting edge?” says Haydee Garcia, who relocated from Mount Sinai Heart Hospital in New York to join UC Davis Health last September as director of the Heart & Vascular Center.

For patients with heart conditions, cardiac credentials offer reassurance that they’re in trustworthy, highly trained hands. In matters of life and death, tangible, measurable, positive results are all that counts. When Lee’s father was born, his family was told he would die by age 11, she says. He lived to be 81. If open heart surgery hadn’t been invented, she says, neither of them would have survived. The fact that technology has evolved to where Lee can now have a valve replaced without “cracking her chest open” fills her with gratitude.

Like Lee, Hernandez grew up in and out of hospitals. It was terrible, but normal for him. Sometimes he tears up, he says, sometimes he laughs. But despite any challenges in front of him, he holds tight to positivity.

“At some point we’re all going to experience grief, and it’s going to come in one way or another,” Hernandez says. “Maybe I experienced that earlier. … Nothing’s forever. But it’s a good reason to keep going because that means the downsides won’t last forever either.”

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Free Parking?

How Sacramento is prioritizing housing for people over housing for cars

After decades in thrall to the car, local developers and legislators are beginning to rethink parking and the role it should play in the city.

Manufacturing a New Vision for Stockton

Stockton manufacturers look to capitalize while operating in the historic region

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Stockton was a manufacturing powerhouse, helping to send items to market like America’s first mass-produced tractors. Stockton’s manufacturing sector declined over many decades, though there are now local leaders working to strengthen it again.

Saving Lake Tahoe

Tourists and the litter they leave behind are threatening the beautiful alpine lake region

Some of the 15 million tourists that visit Lake Tahoe each year are threatening its natural beauty, along with some unruly residents. Now, a new plan is being launched to protect this gem.

Lake Tahoe Is Enjoying Its Best Clarity in 40 Years

While the leaders of the Lake Tahoe region deal with the impact of millions of visitors each year and the trash they leave behind, the lake itself is currently the clearest it has been since the 1980s.