It was the middle of the night. Lisa Kaplan, a Sacramento city councilmember, woke up to the sound of banging. She heard loud whistles. It almost sounded like Mardi Gras. She wasn’t sure what was going on. The banging continued. Then a bright light shone into her bedroom windows; it looked like a strobe light.

She woke her husband. Their minds raced through all the possible scenarios. Were people trying to break into their home? Were all the doors locked? Were their two children safe?

Kaplan called 911. She called the neighborhood security. Her husband wanted to go out and confront whoever it was outside, but they knew that was a bad idea.

The police eventually dispatched patrol units, and while the cops were en route the assailants left. (Kaplan suspected they were somehow listening to the 911 call.) Kaplan and her family were shaken. She knew that the intruders were there because Kaplan, who is Jewish, had been outspoken about the Israel-Palestine conflict, opposing a ceasefire. These same individuals hung a sign over I-5 that read, “KKKaplan Hates Muslims.”

Kaplan’s heart broke when her 8-year-old daughter was reading a book about Martin Luther King Jr. and asked her, “So Mom, is it kind of like how they don’t like us because we’re Jewish?”

“Fixed mindsets can create a meanness in people. With the fixed mindset, you only read stuff that agrees with you. You see the world as a binary place with good guys and bad guys, smart people and stupid people.” Tim Dakin, psychologist, Fair Oaks

Kaplan’s kids were confused, and so was she. Were they safe? She upgraded her home’s security system. She felt afraid every time she took her children to school in the morning. She reminded them not to speak to strangers. She warned her neighbors that they, too, might be in danger, simply because they lived next to people who were Jewish.

So how did this happen? How did we get here? On a surface level, Kaplan’s opposition to a ceasefire — anathema to those supporting Palestine — sparked the personal attacks. But more generally, widening the lens from Kaplan or hate crimes or even the complicated questions of Israel and Palestine, on a more macro level, how did we get here? Why does the world feel so polarized, so fraught and even so ugly?

One big fact is that we can’t even agree on the facts.

From the Big Three to me, me, me

The drivers of divisiveness were decades in the making. From the 1950s to 1980s, the “Big Three” networks of ABC, NBC and CBS created a sort of monoculture — a shared set of TV shows, water cooler talk and even facts that society could agree on. Through these decades, a certain civility was enforced by the Federal Communications Commission’s “fairness doctrine,” which, starting in 1949, required broadcast license holders to present both sides whenever they reported on controversial issues.

The rise of cable, from CNN to Fox News to MSNBC, began to fracture the media landscape. Cable news programs, which came to the fore in the 1980s, could flout the fairness doctrine because it technically only applied to programs broadcast over radio waves. In 1987, the FCC abolished the doctrine, in part because it had become irrelevant in the age of cable news. Now all news programs are free to be as one-sided as they like.

“Rather than the majority of Americans watching and discussing the same things, the audience became increasingly bifurcated,” says Professor Laura Grindstaff, chair of sociology at UC Davis, who studies the role of media on culture. “The proliferation of media outlets, in turn, created intense competition for ratings, which encouraged ever-more sensational content to stand out from the crowd.” (See: Jerry Springer, Howard Stern, Rush Limbaugh.)

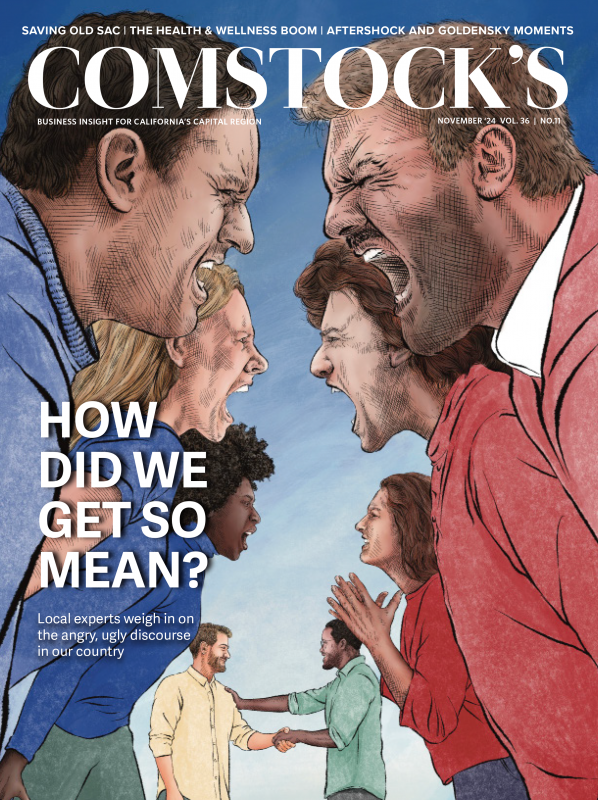

Sacramento City Councilmember Lisa Kaplan and her family have

been the victims of anti-Semitic protests and attacks because she

opposes a ceasefire in the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Then came social media. Why read a newspaper when you can watch a TikTok influencer who happens to share your precise worldview and tells you exactly what you want to hear? “Social media platforms take fragmentation to new levels,” says Grindstaff. “And fragmentation is a necessary if not sufficient precursor to polarization.”

After a third glass of wine, any influencer will admit that speaking to the “middle” is a losing strategy. You get clicks through bold takes, not common sense. You can be bold on the left or bold on the right, just as long as you’re brash and entertaining.

This has parallels in politics. Decades ago, politicians were rewarded for the now-quaint act of turning bills into laws. Consider former California Gov. Pete Wilson, a Republican, and former speaker of the California State Assembly Willie Brown, a Democrat. They worked together on passing budgets. They collaborated on infrastructure bills.

“They disagreed with everything policy-wise, but they both got something out of it,” says Jeff Randle, CEO of Randle

Communications, who served as deputy chief of staff to Wilson and was a top advisor to Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. “They got stuff done.”

Now politicians are punished for even nodding towards the center. Decades of congressional redistricting — by both Republicans and Democrats — have created fewer “toss-up” elections. “If a seat has an edge of 10 points, then everyone running for that seat knows that you don’t have to talk to swing voters, and you’ll be safe until future redistricting,” says Randle. “In many cases, you’re viewed as a traitor if you work with the other side.” Just ask former Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who was ousted by far-right Republicans for being too moderate.

So instead of cutting bipartisan deals, many politicians are incentivized by something else entirely. “Now the system is built on building your own brand,” says Randle. Posting on social media, launching a TV show or hosting a podcast can gin up the base and rack up donations. This happens on both the right and the left (Randle cites both Republican Matt Gaetz and Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez), which leads to increased partisanship and polarization. In a vicious cycle, this further nudges politicians to lean even heavier into the base, which further inflames polarization. Things fall apart; the center cannot hold.

The chamber

Polarization fuels an echo chamber. “Most people interact with like-minded people,” says Cheng Hong, assistant professor in communication studies at Sacramento State. Hong says this is partially explained by a psychological framework called the “dissonance theory,” which suggests that if you come across an idea (or set of facts) that’s in conflict with one of your beliefs, you will feel displeasure. So we avoid this. In some ways we always have, as 1950s-era conservatives flocked to other conservatives; liberals flocked to other liberals. “Social media has amplified that behavior,” says Hong. “It makes it much easier to build an echo chamber around you.”

Larry Meeks, pastor of Williams Memorial Church of God in Christ in Sacramento, sees this behavior in his own community. “We surround ourselves by people who think like we think,” says Pastor Meeks. “We’ve become so ignorant of what the other side is thinking.”

Meeks says that when people learn that he’s a pastor, they immediately assume that because he’s religious, he’s intolerant and unreasonable. “They don’t want to hear anything I have to say,” says Meeks. “The moment you think I’m on the other side, you start labeling me, you start attacking me.”

We see this at church, and we see it online. In 2020, Hong co-wrote a study that explored how social media shaped public discourse. The researchers distinguished between two types of online personalities: “echoers,” who engage primarily with like-minded peers, and “bridgers,” who reach across political divides. Through an analysis of Twitter retweets, likes and mentions, the study found that retweets and mentions largely reinforce homophily — engagement with a similar group. Of the roughly 8,000 users in the study, 7,754 were echoers and 194 are bridgers, which helps explain the online groupthink.

Tech companies are well aware of this dynamic and juice profits by leaning into it. “If you look at the algorithms of TikTok, Twitter (now X) and Facebook, they are giving you the content that you are more likely to engage with,” says Hong. “That also reinforces how you will stay in the echo chamber.” In a now infamous example of how algorithms create an echo chamber, in 2016, Microsoft experimented with an early AI-powered chatbot, called Tay, and released it on Twitter. Trolls fed it hate speech. Tay “learned” the hate speech (including racism and sexism) and began adopting it, so the algorithm fed it more hate speech, and soon Tay began using Nazi language. Microsoft shut down the operation after only 16 hours.

There’s another framework that can help explain the echo chambers. In a model popularized by Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, some people embrace “growth mindsets,” and others have “fixed mindsets,” and fixed mindsets mean we’re stubborn in our beliefs. “Fixed mindsets can create a meanness in people,” says Tim Dakin, a Fair Oaks-based psychologist. “With the fixed mindset, you only read stuff that agrees with you. You see the world as a binary place with good guys and bad guys, smart people and stupid people.” Dakin says that this “binary tension” can stoke anger and exacerbate conflict, which can lead to the ugliness that spilled into Lisa Kaplan’s home.

We’re more likely to express anger, call people names and be toxic when we can do it from the safety of our phones and laptops. “Social media makes it acceptable to hate,” says Kaplan, who calls the online trolls “basement ninjas.” “They’re in some basement and spewing hate. When someone’s in your face, it’s much harder to say mean things.”

Fair Oaks psychologist Tim Dakin says people gravitate toward

others with a similar mindset.

All of these factors — political partisanship, social media echo chambers, a psychological tendency to stay “fixed” in our mindsets — help explain why the discourse can feel so awful. Then one final factor exacerbates the problem: foreign agents. “Bots and plants from other countries want to sow discord in the United States,” says Kaplan.

“We’ve seen that in the last two presidential elections.” The widening left/right schism has been weaponized by Kremlin-backed troll farms. In 2016, for example, in Texas, Russian operatives posed as activists to create a pro-Muslim rally (from fake Black Lives Matter accounts) and an anti-Muslim rally (from a fake group called “Stop Islamification of Texas”) on the same day, directly across the street from each other, hoping to incite violence.

People, not partisans

All of this can feel bleak, and there are no easy solutions. So what can we do? Civilization-saving advice is outside the scope of this article, but on a grounded and personal level, it can help to do a few small things. The first is to welcome media that challenges your own worldview. Pastor Meeks, who’s conservative, watches MSNBC to expose himself to other perspectives. “I make it my business,” says Meeks, “to listen to the other side.”

The “other side” can feel demonic when you’re staring at a tweet, but you can remember their humanity when you’re sharing tacos. “You can solve almost anything when you have that personal relationship,” says Randle, “when you know about somebody’s kids, instead of coming from a place of hate.” He views Pete Wilson and Willie Brown’s personal, human-to-human relationship as one reason they accomplished so much. We can do this in our own lives. How many people in your life don’t share your political views? Consider welcoming more.

Finally, just for our own sanity, it can help to take a longer lens perspective. When I conducted research for a book I was writing that’s set in the revolutionary era (“Alexander Hamilton’s Guide to Life”), I was strangely heartened to see the familiar nastiness, insults and toxicity even in the early days of our democracy.

In the election of 1800, a prominent supporter of Thomas Jefferson, the pamphleteer James Callender (a TikToker of his day), called John Adams a hermaphrodite. Adams’ supporters shot back, warning that electing Thomas Jefferson would bring “murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest.” And in 1828, the supporters of John Quincy Adams called Andrew Jackson a murderer and accused his wife of bigamy. In 1856, Senator Charles Sumner, after giving an anti-slavery speech, was beaten unconscious by a cane in the halls of Congress.

To some extent this ugly strain has always been present; now we can just see it more clearly. “Humans haven’t changed that much,” says Dakin, who notes that centuries and millennia ago, conditions were generally worse across the board and especially for women and minorities. “I do think that life is better today.”

Kaplan, even after being harassed at her home and concerned for her children’s safety, is still hopeful that we can remember our shared humanity, to befriend others who might not share our politics, and to see people as people and not partisans. “It almost sounds naive, but it isn’t,” says Kaplan. “I wish we started caring about our neighbors and our friends and each other more than we do about the social media narrative, or who’s right and who’s wrong,” she says. “Kindness should come first.”

Recommended For You

How the $20 Minimum Wage Is Playing Out

The law was written to target big fast-food chains — but that’s not how it’s working in the Capital Region

As economists and advocates debate the merits, the experiences of restaurant owners in the region offer some evidence of what happens in practice.

What’s Holding Up Valley Rail?

The need and the plan are there, but bureaucracy once again slows progress

The project has been caught in spiraling delays, and launch dates have been pushed back to 2030. The San Jose Regional Rail Commission broke ground on just one of the half dozen proposed new stations as of late summer 2024.

The Value of Art

4 years out of the pandemic, Sacramento’s arts scene brings in tourism and tax dollars

A 2022 study conducted by Americans for the Arts in partnership with Sacramento Alliance for Regional Arts found that nonprofit arts- and culture-related activities in Sacramento County injected over $241 million into the local economy.

Is Our Future Tied to the Tracks? with James Stout

PODCAST EPISODE: Journalist James Stout delves into his latest feature for Comstock’s “What’s Holding Up Valley Rail?” where he investigated delays in railway expansion throughout the Central Valley. We discuss the hurdles that are baked into the system, changing attitudes towards public transit and whether hopping on a train might be more commonplace in future America.

Shining Lights

Hobrecht Lighting and Lofings Lighting have longevity while competitors have come and gone

At a time when anyone can order lighting fixtures off Amazon or wander the aisles of Home Depot or Lowe’s and select something readily available and cheap, visiting Hobrecht or Lofings can feel like a trip to a different era. Still, there’s a story worth telling connected to each of these Sacramento stores which shows how family businesses can endure even in changing times.

Roseville’s Unique Shopping and Entertainment Gathering Place

Family business spotlight: The Denio family embraces the future while honoring their roots

Eric and Tracy Denio remember Roseville before it was a suburban powerhouse — back when their childhood days were spent roaming among fields, ranches, ponds and gravel pits. Flash forward to today, and Denio’s Farmers Market & Swap Meet is surrounded by oceans of homes and shopping centers that span for miles in every direction. But one thing that hasn’t changed is its ethos.

A Pioneer in Organic Farming

Family business spotlight: Pleasant Grove Farms in Sutter County grows popcorn, wheat and rice the natural way

Driving along a country road in rural Sutter County and seeing endless rows of corn, you can’t help but think of the movie “Field of Dreams.” The Sills family decided to build their dream eight decades ago. Pleasant Grove Farms, a family-owned, certified organic grain and bean farm, has been growing corn and other crops for nearly 80 years.

A Stockton Institution

Family business spotlight: The Bank of Stockton has been operating for 157 years

Founded in 1867, Bank of Stockton is the oldest bank in California still operating under its original charter. This longevity and continuity in serving communities with Bank of Stockton branches — as of November, there will be 21 locations throughout the Central Valley — sets this family business apart.