A Swainson’s hawk swoops down from a dead tree branch to the edge of a farm field in Natomas. The hawk snatches a rodent, then flies to the top of a power pole for one last scan of the field before soaring towards the Sacramento River. The rodent is still dangling from the hawk’s talons.

It is nesting season, and Swainson’s hawks are known to mate and raise chicks in trees along the Sacramento River. The tall trees are good for nests and stand next to open fields that make good hunting grounds.

The Swainson’s hawk is considered threatened in California, the result of lost habitat. Yet it is doing well in the Natomas Basin, in part because of a conservation plan that sets aside land for habitat, like the farm where the hawk foraged.

That could change due to four major development projects that are planned in the Natomas Basin. The projects would replace important wildland with homes, warehouses and other buildings.

Such challenges are becoming more common as developers seek to build outside of established communities on the fringes of unincorporated Sacramento County. About 100,000 housing units are planned for greenfield property in the county, with about 10 percent built and the rest coming later. That equals half the existing housing in the city of Sacramento.

Environmentalists worry about the impacts of greenfield development: It increases greenhouse gas emissions as people commute longer distances and causes the loss of habitat and open space, which gives the region its character and makes it a good place to live.

Such issues are putting pressure on developers. “We are facing crises on several fronts,” says Tim Murphy, president and chief executive officer at the North State Building Industry Association. “We have a housing crisis. We also have a climate crisis. … The industry is responding responsibly to these challenges.”

The region has been suffering through a housing shortage for several years. The population has continued to grow, driven in part by Bay Area residents fleeing the high cost of housing there and creating a higher demand in the Capital Region. Demand has exceeded supply, driving up home prices and rents here.

Greenfield development could help ease the region’s housing crisis, Murphy says. Single-family homes in the new communities cost more than the average home for sale in Sacramento County. But the new homes fill a market need, especially for higher-income residents moving here from the Bay Area, Murphy says. More houses on the market should drive down the cost of all housing, he adds.

A red-winged blackbird flies in a field of mustard on Natomas

Basin property where developers want to build.

Sacramento County planners expect 14 master planned developments outside existing communities. The new communities will have residential, commercial and other types of development on properties of 100 to 6,000 acres each. Combined, the new communities will cover 50 square miles, half the size of the city of Sacramento.

The Sacramento County Board of Supervisors has approved eight of the communities, all but one in the eastern part of the county and most clustered near State Highway 16. With one exception, the remaining communities are planned for the northwest part of the county, in the Natomas Basin and Elverta.

Not all the proposed development is likely to get built. The Sacramento Area Council of Governments, a regional transportation planning agency, recently found that the county could meet almost all its housing needs with proposed development in its existing communities (see sidebar). This shows that the county is planning for much more housing than is likely needed, perhaps dramatically so.

The planned greenfield development will also take a long time to complete, probably decades. Regulatory requirements, including environmental ones, will add years to the projects. Business issues, such as changing consumer demand, financing and construction, add to the timeline.

Consider the example of Vineyard Springs, the county’s first master planned community and in its southeast corner. The county Board of Supervisors gave initial approval to the project in June 2000. Twenty-four years later, the community is only two-thirds complete.

The Natomas Basin projects could take longer than the other county projects because they involve protected species, including the Swainson’s hawk and the giant garter snake. The Natomas Basin runs from Garden Highway to south Sutter County and from the Sacramento River to Steelhead Creek.

The basin was one of the fastest growing areas in the region until the federal government enacted building restrictions in 2008 because of flood risks. The restrictions were lifted in 2015.

Developers still face hurdles in the area because of the Natomas Basin Habitat Conservation Plan, approved by a federal judge in 2005. The Natomas Basin Conservancy administers the plan by collecting fees from local governments and land donations from developers to protect threatened species.

Sacramento County, which is being asked to approve three of the four major projects in the basin, elected not to join the plan. But the county is still subject to the same state and federal wildlife laws that govern the plan and would have to get approval from wildlife agencies to allow building there. County planners have said the plan would have to be revised for the projects to get approved.

Heather Fargo was a Sacramento councilmember when the plan was negotiated and mayor when it was approved. The plan allowed the city to develop ecologically sensitive parts of Natomas in exchange for conserving property. Now she is leading the fight against proposed developments threatening the plan.

“As a former mayor and a city person, I believe developments like these should be in existing city limits and not in places pretending to be cities,” Fargo says.

Fargo and other environmentalists have been lobbying county supervisors and Sacramento City Council members to oppose the Natomas Basin projects. (Developers of a fourth basin project, called Airport South, have asked the city to annex the county property into the city.)

Fargo and other environmentalists say the Natomas Habitat Conservation Plan will fail to meet its goal of setting aside 8,750 acres if the proposed developments are built. There won’t be enough available land to conserve, they say.

One project faces a particularly tough challenge with environmental regulations. The proposed Upper Westside project would build housing and other development on 2,000 acres on the Garden Highway in an area called “the boot.” The project would cross an area called the “Swainson’s Hawk Zone,” a 1-mile-wide strip of land next to the Sacramento River set aside for protection in the Habitat Conservation Plan. This is where the bulk of the hawk’s nests have been found in annual surveys. Nick Avdis, an attorney representing the developers, declined to comment about the project because an environmental impact report on Upper Westside was still being completed.

Doug Ose, former Sacramento congressman and one of several developers involved in Grand Park, the biggest of the planned communities in the county, says he has hired scientists who will argue that land outside of the basin can better serve the needs of the Swainson’s hawk than property in Natomas Basin. He plans to buy such land to mitigate the loss of developed land in the basin. Murphy of the North State Building Industry Association says developers of other basin projects have plans to buy mitigation land to offset habitat loss.

On the other side of the county, major changes are in the works. Drive State Highway 16 east from Bradshaw Road and the development pretty much disappears. Some scattered housing and commercial development can be seen here and there, but it is mostly open fields leading to Rancho Murieta and the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

Much of the area will be filled with development if county plans materialize. Subdivisions will line Highway 16 from South Watt Avenue to Sunrise Boulevard. About 10,000 housing units have already been built on greenfield property in the Vineyard area, south of the highway.

Loss of open space is a great concern for residents. “Natural spaces, trails, and community assets make the Sacramento region special,” according to Valley Vision’s 2023 Livability Poll. “In this poll and others dating back to our first public opinion poll in 2017, people most value the natural places in our region, including parks, trails, waterfronts, and open space. These types of places ranked as the top two most important places identified by respondents.”

Developers have incorporated open space into master planned communities with parks and greenbelts. But staff at the Sacramento Area Council of Governments, known as SACOG, say that preserving open space is an argument for concentrating housing in existing communities. Another reason: curbing greenhouse gas emissions, which go up with additional driving required by building housing further away from jobs and stores. Greenhouse gasses, scientists agree, are causing climate change. SACOG’s board this year has taken up land-use planning in part to make sure the region meets state greenhouse gas emission requirements.

The SACOG board, made up of elected officials from the region, in June approved a land-use plan that excluded nearly all the greenfield development proposed in Sacramento County. Meeting the state’s greenhouse gas emission standards was the main reason.

Developers are addressing these challenges by adding job and service centers within their master planned communities, but not fast enough to change the SACOG plan.

The SACOG land-use plan will determine which areas receive transportation funding, as state and federal transportation funding must be approved by SACOG, says Executive Director James Corless. The board expects to vote on transportation projects later this year.

Former Sacramento Mayor Heather Fargo next to a farm conserved as

part of the Natomas Basin Habitat Conservation Plan.

The SACOG plan does not prevent Sacramento County from moving forward with its master planned communities, and the county intends to do so, says County Spokesman Ken Casparis. “Developers are responsible for paying for transportation improvements necessary to mitigate traffic impacts caused by their development,” he says.

Except when protected species are involved, final approval for the projects lies with the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors. Over a 10-year period ending in April of this year, development interests — developers, contractors, realtors and other construction professionals — contributed $1.6 million in campaign contributions to the five supervisors currently on the board. That adds up to 39 percent of the campaign contributions received by the supervisors.

Under a state law approved two years ago, city and county elected officials must recuse themselves from certain decisions that would financially benefit people who contributed $250 or more to their campaigns in the previous 12 months. County Supervisor Pat Hume, along with a Rancho Cordova councilmember and business groups, unsuccessfully challenged the law in Sacramento Superior Court.

Hume argued that the law would make it impossible for him to carry out his elected duties. Hume, elected to the board in November 2022, received a total of $545,000 in campaign contributions from development interests through April of this year.

“I don’t vote the way I vote because of the money I get,” he says. “I get the money I get because of the way I vote.”

Hume worked for a family real estate company before joining the board. Three of the four other county supervisors have similar backgrounds: Phil Serna worked as a development planner; Sue Frost is a real estate broker; and Patrick Kennedy worked as a construction lawyer.

Murphy says builders need political assistance when regulations add an average of $120,000 to the construction of a home. “We’re well behind the number of units we need to meet the existing demands,” he says.

Recommended For You

Leading the Way on Housing

Multifamily unit construction in Sacramento 'is booming'

In the last four years, Sacramento has approved more than 11,000 housing units, the third-highest total in the state, according to figures from the California Department of Housing and Community Development. The city’s total of approved housing trails only Los Angeles and San Diego, both of which are much larger cities.

The Need for Nurses

The Capital Region has a nursing shortage. Here’s what health care systems, schools and others are doing about it

National Center for Health Workforce Analysis figures from November 2022 show there could be a shortage of over 78,000 full-time registered nurses in the U.S. by next year, and that the shortage could last several years. CalMatters reported in July 2023 that California was short around 36,000 licensed nurses, citing figures from UC San Francisco, which studies the nursing workforce.

Are We Ready for the Electric Revolution?

The Capital Region is leading the charge to make California EV compliant in the next decade

These days, there is a sense of possibility in Sacramento when it comes to zero emissions technology. Sacramento may not have the population numbers of New York or Los Angeles, but when it comes to EV infrastructure the California capital plays second fiddle to no city in America.

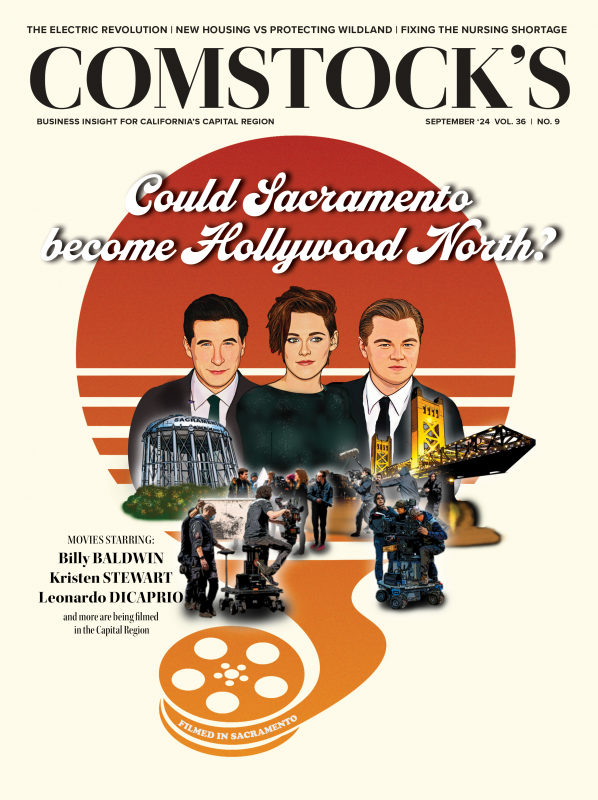

Ready, Set, Action!

Filmmakers big and small are finding the region a congenial place to make movies

For several days this winter, Sacramentans got to play “Spot the Movie Star” while Leonardo DiCaprio and William Baldwin were both in town filming two different movies at locations all over the city. It begs the question: Could Sacramento become Hollywood North? The city and nearby Placer and El Dorado counties have a growing film industry that brings millions of dollars and thousands of jobs into the region.

We Oughta Be in Pictures!!

FROM THE PUBLISHER: Our region has long been one of Hollywood’s well-known secrets. Because of the area’s natural beauty and close to year-round clement weather (the two compelling reasons that made filmmakers leave New York in the early 1920s for a stronghold in Southern California), movies, TV shows and commercials have been shot here for years. What if we had our own film studio?

From Farm to Glass

They’re just miles apart, but Capital Region wine regions are distinctively different based on their climate, terrain and soil

Each of our four wine regions has its own unique terroir, a French term describing the soil, climate and sunshine that give wines their distinct character. These winemakers want consumers to consider their wines farm-to-fork — that is, farm-to-glass.