For California labor lawyers, the 2012 Brinker v. Superior Court ruling was something akin to Brown v. Board or Roe v. Wade. In a case involving meal and rest breaks for hourly employees, the court ruled that businesses must have a policy giving workers those breaks — but they don’t have to ensure that staff actually take them. It seemed like near-total victory for business.

In the world of labor law, the decision was “huge,” says employer-side labor lawyer Dennis Murphy. But another part of the decision cheered employee-side attorneys by making it easier for them to turn wage-and-hour lawsuits into class-action claims. Today, with wage-and-hour cases increasing and changes on the way for sick leave and minimum wage, businesses have to be more proactive than ever to avoid litigation.

By at least one measure, the number of wage-and-hour claims is climbing. In the past three years, the number of federal lawsuits filed related to fair labor standards in California’s Eastern District court rose by about 18 percent compared with the three years prior. (No data are available on the number of such lawsuits filed in state courts.)

If that increase is real, the reasons for it depend on where you look. One possibility is that there’s just more wage theft than in the past. In 2012 (the latest year for which data are available), the state Department of Industrial Relations assessed more than $3 million in unpaid wages, the highest amount on record. The previous year it levied almost $35 million in civil penalties for various wage and hour violations, the largest amount in a decade.

Alternatively, an analysis by employer-side law firm Seyfarth Shaw argues that federal and state wage and hour laws are increasingly complex, so companies are having a hard time complying with them.

For plaintiffs, getting a case certified as a class action transforms it from off-Broadway to Hollywood. Class certification lets workers get in on lawsuits they might otherwise avoid because they fear retaliation. The identity of plaintiffs is much better protected in a class action, says Gary Goyette of Goyette & Associates in Gold River, which has represented both employees and employers. They also mean bigger paydays for lawyers since attorneys’ fees in class actions are much bigger than in other cases. That makes them attractive to plaintiffs’ lawyers, says Jennifer Madden of Sacramento’s Delfino Madden O’Malley Coyle Koewler.

The decision on the Brinker case and a few subsequent judgments have made wage-and-hour cases easier to certify. Several judges have ruled that lawsuits brought over out-of-compliance company policy — say, one that fails to inform hourly employees of their right to meal breaks within the first five hours of their shift — almost automatically get certified as class actions since those policies apply to everyone. Two new state labor policies could trip up unwary employers. The mandatory 3-days-minimum of sick leave that started on July 1 will require more documentation, Madden says. Employers will have to keep records for three years on each employee’s hours worked and sick leave accrued and used.

And with the state minimum wage increasing to $10 an hour by January 2016, companies will need to attend to the salaries of their exempt staff: Exempt employees generally must earn at least twice what nonexempt workers do. Translated, that means minimum salary requirements for exempt employees will increase to $41,600.

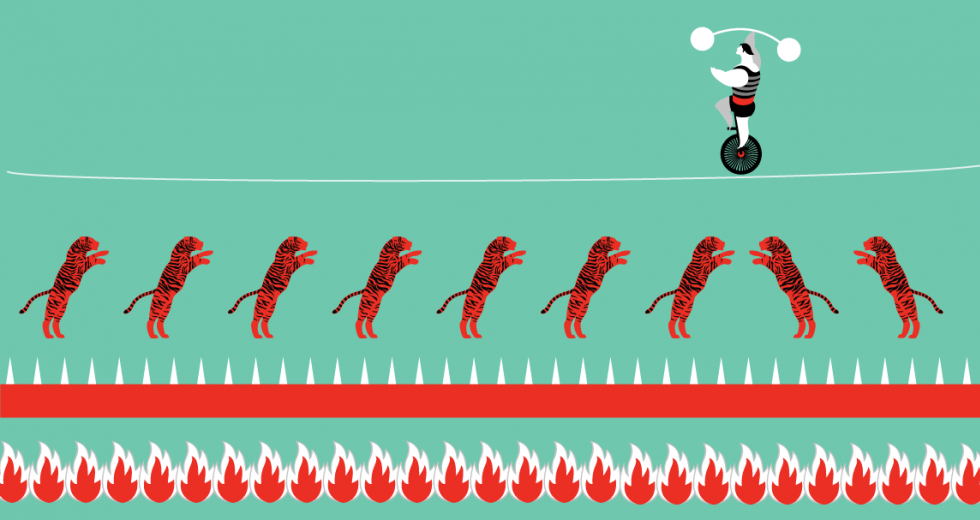

As always, companies protect themselves from wage-and-hour claims by assuming the worst — that one poorly considered word choice in a policy could be the tripwire for a lawsuit. “It’s easy to violate California wage-and-hour laws,” Murphy says.

Madden suggests that companies have an experienced human resource professional do a thorough internal audit of company policies to ensure that they comply. They also should do internal trainings on compliance for front-line and mid-level managers, who are best positioned to spot possible problems but often don’t know what’s legally required.

Goyette suggests something more if a company has never had its policies reviewed: Hire a wage-and-hour lawyer to do the review. Such reviews can cost $250 to $450 an hour, and a comprehensive review might take as much as 40 hours since it involves not only looking at company manuals but even scrutinizing pay stubs. After that, he advises having annual policy reviews to keep up with changes in the law.Those who can’t afford either option should at a minimum visit the California Chamber of Commerce website, which offers customizable materials, such as an employee handbook creator, tailored to state law.

What won’t work is doing an Internet search for a standard employee handbook, Madden says. Those products aren’t customized enough to let you navigate the minefields of state labor law. For example, a policy stating that a worker is entitled to a 10-minute rest break for each four hours of work would seem to comply with state law on breaks. But it doesn’t unless it also makes clear that a “major fraction” of an hour counts toward the four hours, notes Karen Kubin, partner at the San Francisco office of Morrison Foerster.

Flagging such arcana is how attorneys get paid — and inoculate companies against the next wave of lawsuits related to pay and working hours.