The shade of the warehouse does little to quell the triple-digit heat. Still, Thomas Nesbit, 21, and Jared Smedly, 22, volunteer their afternoon to construct a picnic table from scratch. Next week, they will likely sell the table for $150 at the Sacramento Regional Conservation Corps reuse store, a retail outlet for construction materials, which funds the young men’s education and paid job training.

Some of their peers are across town hosting an information booth at the California State Fair. Nesbit and Smedly are two of nearly 130 adult students working their way through various academy-style career and education programs at the SRCC, a 25-year-old nonprofit that integrates education, job training and work experience on conservation and construction projects for those age 18 to 25.

“The day my son was born I knew I wanted to be there for him more than my father was there for me,” says 23-year-old Octavio Ramirez, a high-school dropout with a history of gang activity and an interest in sustainable construction and landscaping. “This program has helped me a lot. It’s taught me about getting along with other people. It’s about you and the world, not just yourself. I feel like I’m ready to go out and get a job.”

Corps members, for the most part, join SRCC because they face a number of complex barriers to employment, including incarceration, lack of work experience, low academic skills or personal, behavioral and social problems. Many have felony records, few have driver’s licenses and 95 percent have not completed high school.

The outcomes of the program — which has served more than 5,000 participants —have been tremendous, says Lorna LaZansky, the program’s director.

“They’re not going back to prison, and they advance at least two levels academically, so we make tremendous progress,” she says. What’s more, even those with felonies are exiting the program with jobs.

Across the Capital Region, students of all ages and backgrounds are reporting academic advancement, improved job readiness and college acceptance as the result of academy-style learning. During the past two decades such programs have been developing at schools and nonprofits throughout the nation and are gaining traction, popularity and funding locally.

Cordova High School has four state-funded California Partnership Academies on campus. The first, a polytechnic academy, was established at the school in 1992 in an effort to link academic achievement with meaningful career development in the engineering industry. Next, the school implemented a similar business and technology academy, which has since become nationally recognized for excellence. The school also provides a rigorous culinary academy and a public safety academy.

The Oakmont High School Health Careers Academy is a college prep program that stresses real-world application for students interested in medical careers. Freshmen students interview for admission and spend the following three years participating in or observing medical activities at local hospitals, including monitoring EKGs, invasive surgeries, interpreting for non-English-speaking patients and administering CPR.

A number of other high schools in the region have similar academy-style programs too, including Grant High School, which has a justice administration program; Elk Grove High School, which has an agriculture program; Laguna Creek High School has a media-focused program; and Del Oro High School has a culinary academy.

While all students are welcomed and encouraged to participate — including both advanced-placement and special-needs students — academies at the local high schools and nonprofits are primarily targeted toward at-risk participants who are economically or educationally disadvantaged.

“We have gangbangers coming in, and by the time they’re done they’re going to college. They didn’t even think they could graduate. We are helping these kids turn around from horrendous hardships,” says Linda Greer, a teacher at Folsom Cordova High School who heads the school’s academies department and its public safety academy. “We were finding that students in the academy have better grades and better attendance rates than the school’s norm. And there are fewer disciplinary issues with the academy students than the norm as well. These are now students that are going to move right into four-year institutions.”

The results at Folsom Cordova High School are not out of the ordinary. Earlier this year, the Career Academy Support Network at UC Berkeley published a synopsis of more than a decade of academy research compiled by dozens of institutions, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the U.S. Department of Education. Researchers found that academy students drop out of high school at half the rate of general population students in California; they are equally as likely to enroll in a four-year college as advanced-placement students; males who graduate from academy programs earn 17 percent more, on average, than their non-academy peers, and were more likely to be custodial parents living independently with a spouse or partner.

“We have gangbangers coming in, and by the time they’re done they’re going to college.” —Linda Greer, teacher, Folsom Cordova High School

“I don’t want to work for nobody. I want to own my own [business]. I want to drive trucks. So I’m thinking I’m going to join the Army and save my money to buy my own truck,” Nesbit says. “But I don’t know if I’m ready for the Army — if I could handle myself with taking orders and people yelling down to me — so I am going to stay and work here until I am better prepared.”

By developing small, personalized and rigorous curricula, students are academically and socially challenged in an environment that offers increased accountability and interpersonal relationships.

“They understand your background at this school, and they keep you motivated. If you’re down, they notice; they talk to you about your problems,” Ramirez says. “If you come in at a two, you’re going to end your day at a 10.”

But the real value of the program comes from what happens beyond the classroom. For students throughout the state involved specifically with California Partnership Academies, such as those at Folsom Cordova High School, hands-on industry training and intimate access to business and civic leaders is the key.

At Folsom Cordova High School, Greer’s first-response students train alongside the Sacramento Metro Fire Department, and a program called Sacramento County Explorers connects students with the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department on weekends and evenings. In addition, two of Folsom Lake College’s criminal justice courses are taught on the Folsom Cordova High School campus, giving students access to six transferable college credits before graduation.

Meanwhile, students in Liberty Ranch High School’s ACE program for architecture, construction and engineering worked on designs for a proposed transportation hub at the railyards in downtown Sacramento. The competing groups, which included a team from Folsom Cordova High School’s polytechnic academy, had a budget of $20 million and were responsible for designing intermodal transportation, developing a budget, managing a construction schedule and presenting their plan to a panel of local professionals.

The Liberty Ranch ACE group won for its design that featured a LEED-certified transportation hub, parking garage, a sculpture park, amphitheater and other amenities.

“This is where the business community becomes so important,” Greer says.

California Partnership Academies are funded annually with $81,000 each. Participating schools are required to match the funding through monetary and in-kind donations from local businesses and organizations.

“I’ll exceed $150,000 in in-kind donations for my students in the form of guest speakers and [events],” Greer says. The business and technology academy regularly brings in upward of $300,000 in in-kind donations, and the engineering academy will bring in about the same through donated construction materials and supplies. Cache Creek Casino recently donated $15,000 worth of surplus building materials, for example.

In addition, all students in their junior year are paired with a mentor from the business community. Last year, more than 70 students from the business and technology academy alone were paired up with professionals representing businesses and organizations ranging from the Rancho Cordova Chamber of Commerce to Vision Service Plan and River City Dental.

Ashley Donahue is an insurance coordinator at Vision Service Plan. She served as an academy mentor this past year and is a 2007 graduate of Folsom Cordova High School’s business and technology academy.

“I was interested in photography, so my mentor helped me find lots of colleges I could attend that had good programs. She went above and beyond with finding me schools,” she says. “It’s a good social networking thing. And if you have personal problems, you are allowed to talk about that; it wasn’t just talking about college.”

Donahue’s mentor assisted her with finding her first job out of high school. Less than six months later, Donahue was working alongside her mentor at VSP.

“I have already been promoted, but I see her all the time … and she is still encouraging me to take photography classes in my spare time,” Donahue says. “Without the academy and the connections, I certainly wouldn’t have this job.”

Recommended For You

Teach it Forward

How one woman paid her education forward

Asha Canady’s parents didn’t go to college. Her brothers didn’t make it out of high school. But it was expected, from a young age, that Canady and her twin sister would succeed in higher education.

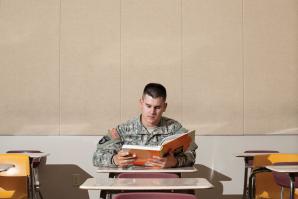

The Battle After

Back from war, student veterans struggle on campus

Nathan Johnston has contemplated his own death several times over.