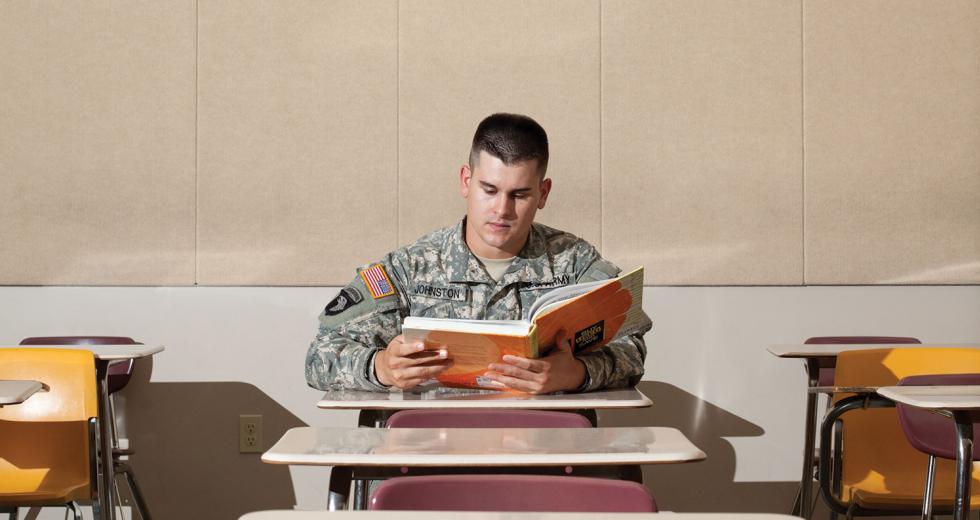

Nathan Johnston has contemplated his own death several times over.

After high school graduation in 2008, Johnston’s parents wanted him to attend college. He joined the Army instead and was deployed to Afghanistan, where he rappelled out of Chinook helicopters and pitched his body into bunkers ablaze with machine gun and mortar fire.

“The area we were in had a lot of enemy contact,” says Johnston, 21. “I didn’t know if I was going to make it out. There were plenty of times I thought it was my time to die.”

But he did make it out, and these days the Auburn resident and Purple Heart recipient dreads a different kind of challenge: writing a college English paper.

“It’s been four years since I wrote an English paper,” Johnston says. “My English teacher has been a big help; she helps me one on one. Math has also been difficult. All the things I learned in high school math, I’ve totally forgotten.”

After leaving the military last November, Johnston returned to school at Sierra College for the spring semester. He aspires to transfer to a four-year college, earn his psychology degree and work as a counselor or therapist, perhaps helping other veterans returning from war.

First, though, he has to transition from a life of discipline and hierarchy to one of choice and relative chaos, especially acute on a college campus.

“It’s just different, dealing with others who haven’t had my experiences,” Johnston says. “There’s no rank structure. I feel isolated, especially from friends who I went to high school with, who are now juniors in college and leading typical college lives.”

Johnston may feel alone, but he’s part of a wave of veterans returning from war and going back to school, many with the post-9/11 heir to the G.I. Bill.

The war in Iraq is over, and 22,000 troops will return from Afghanistan this fall. According to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, the number of veterans receiving benefits soared 16-fold to 555,329 within three years of enactment of the G.I. Bill of 2008, which dramatically expanded educational and other support benefits.

Under the latest rendition of the G.I. Bill, signed by President Obama in December 2010 and known as “G.I. Bill 2.0,” many enroll in online schools or vocational programs, but a growing number of student-veterans attend traditional colleges and universities.

Many U.S. colleges are welcoming the influx, but some veterans’ advocates claim that other schools are ignoring mandates to provide support and resources to the student veteran population.

When asked whether the 6,700 colleges and universities approved as eligible to educate veterans on the G.I. Bill were doing enough to support former troops, Rodrigo Garcia, national chairman of the Student Veterans of America, gave them “an overall C+.”

Garcia says many individual colleges and universities are excelling at supporting soldiers, but others are failing.

Career counseling needs immediate improvement to help mitigate spiraling unemployment in the ranks, he says, a reflection of the challenges of reintegration. As of January, 9.1 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans nationwide were unemployed, higher than the overall rate of 8.3 percent.

The national job market is competitive as it is, and many veterans are attempting to enter the workforce alongside civilian peers who have completed school and already have a few years of job experience under their belts. According to the national Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, many individual National Guard and reserve units returning home are seeing jobless rates of up to 30 percent as service members realize the setbacks of missed education or job experience and employers shrink from taking on an employee who might have physical or emotional problems or who could be deployed again.

Did You Know? Eighty percent of California’s firefighters, law enforcement officers and emergency medical technicians are credentialed at community colleges.

This increasing number of former soldiers on campuses has college staff in the Capital Region rushing to meet the space demands and emotional needs of a new kind of student.

Sierra College President Willy Duncan says veteran enrollment at the Rocklin campus is climbing. In 2001, there were 200 vets enrolled; currently, 600 to 650 vets are on the campus of 22,000 students.

Duncan attributes much of the increase in veteran enrollment to the solid resource and support network in place at Sierra College. The campus has had a veterans’ center since 2001, ahead of most other colleges, and continues to expand vet services.

“Many veterans are not from the area but have chosen to live here and go to school because of the resources we offer,” Duncan says. “Some find out by word of mouth when friends tell them what we provide.”

With community colleges already impacted by increased enrollment, Duncan says there are concerns about whether veterans can get classes for on-time graduation.

“We’ve had to restrict enrollment overall, but statewide, vets get priority registration,” he says.

Duncan says many vets are attracted to careers in law enforcement, criminal justice and firefighting.

“They tend to pursue programs where their military training helps them succeed,” he says. “They like doing physical work, often outdoors, and they get the camaraderie they miss in the military.”

Catherine Morris, a veteran, started the veterans program at Sierra College and is credited with the rollout of services. She launched the Veteran’s Center to help returning soldiers deal with the stress of reorienting to civilian and academic life.

“Many vets were coming back saying they were more intimidated . . . going to college than being in combat,” Morris says. “At first, it shocked me, because they’ve been in combat situations. But it makes sense, because in combat, you’re part of a team with a support system, and you train so you know what you’re doing out there.

“But on a college campus, they feel alone, they’re older, they may not have people in their family who have gone to college, and they have to jump through all these hoops.”

Many returning vets face basic challenges, such as finding a place to live, learning to communicate with family and friends, financially making ends meet after military pay stops and dealing with combat stress and injuries.

“Some are doing fine, but others are having a difficult time,” Morris says. “It’s not like turning off a light switch, going from combat to a college campus. And they don’t have a battle buddy; they are completely on their own.”

Johnston was diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury after the truck in which he was riding detonated a roadside bomb. He suffered a concussion and wrenched his back.

“I was out of it for a couple of days,” Johnston says. The concussion slightly affected his memory.

“There’s no advice on getting a job or what you might want to do. They just have you sign something and thank you for your four years. You’re there standing with your bag in your hands, and they put you out the door.”

Greg Hughes, Iraq war veteran, and student, Sierra College

He also deals with the normal stress of combat and the plunge into civilian life.

“I have a small sense of paranoia,” he explains. “It takes a good six months to get your head out of the war zone. I’m very aware of things around me and am always looking over my shoulder.”

Greg Hughes, a 31-year-old Santa Cruz native, enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1998 at age 18. He recently returned to school at Sierra College after being deployed twice to Iraq.

“I went to Iraq in 2002 as part of the invasion,” he says. “We were staged in Kuwait and pushed into Baghdad in armored transports. Pretty much the whole time, they shot at us, and we returned fire. It was more confusing than anything. They kept us moving day and night; we outran our supplies, and it got intense.”

Hughes also did ground patrols of Baghdad streets, where one of his buddies was shot but survived.

When Hughes came home and left the military service, he got various construction jobs in Texas and, for a period, owned a door company. Hughes never had trouble getting work, but he understands how lost returning troops can feel.

“It was challenging, because there’s no preparation for when you get out,” Hughes says. “There’s no advice on getting a job or what you might want to do. They just have you sign something and thank you for your four years. You’re there standing with your bag in your hands, and they put you out the door.”

Hughes decided to quit his job and use the G.I. Bill to go back to school.

“I was intimidated when I walked onto campus, because of my age and the amount of time since I’ve been in school,” says Hughes, who hopes to transfer to Sacramento State to earn an engineering degree. Morris says community colleges are absorbing many of the veterans going to school. At Sacramento State, 95 percent of the veterans are transfers from Sierra College.

Hughes is interested in engineering because he likes to design and build. But after just a few weeks at school, he remains nervous about his choice.

“Yes, I’m worried,” Hughes says. “But I made a decision, and I’m going to stick with it.”

Johnston is a work/study student in the college’s veterans’ center and can spot a returning veteran struggling with emotional or health issues.

“Some of the things we saw, you know, soldiers had a hard time with those,” Johnston says. “We have a hard time coping with things. If they hear a book drop and they turn quickly, I know how they feel. Sometimes they are more slow and nervous, and I’m more patient with them.”

He helps new students with renting a home, registering for classes and filling out paperwork for G.I. Bill assistance.

“They have an idea what they want to do, but don’t always understand how to get there,” Johnston says. “Many get out of the Army and get a construction job because they’re too scared to get into school. When I got out of the Army, I was only a high school graduate. I had lost time. Luckily, I have a loving sister who helped me sign up for classes, but there are many people who don’t have that.”

Recommended For You

Renewable Resources

Los Rios prepares to roll out updated student support services

Thomas Hanns was homeless when he first enrolled in classes at Sacramento City College, one of four main campuses that make up the Los Rios Community College District.