A healthy human body is a fortress with guards at the ready to seize intruders. When under attack, these guards (antibodies) secrete chemicals that recruit and grow immune cells. The cells then seek and destroy the intruders (antigens) to protect the fortress.

“The immune system is very good at finding things that don’t belong in the body — whether that is a virus or transplanted organ or tissue — readily attacking it and breaking it down to remove the threat,” says Maelene Wong, CEO and co-founder of ViVita Technologies, a medical device startup in Davis.

Wong knows the ins and out of the immune system because she is on a mission to save lives by penetrating the body’s automated defenses. Her work began as a graduate student at UC Davis, where she specialized in tissue engineering. Now, with ViVita co-founder and board chairman, Leigh Griffiths, Wong is developing platform technology that removes antigens from animal-derived tissues, an innovation that could help eliminate the shortage of donor organs and tissues.

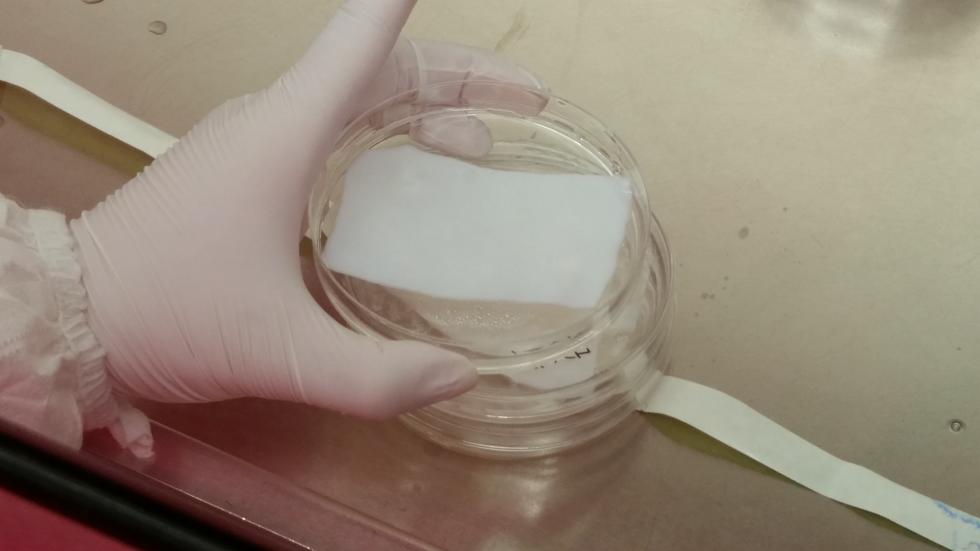

Cow tissue undergoes the ViVita Technologies process.(Photo

courtesy ViVita Technologies)

In 2015, U.S. doctors performed a record 30,000-plus organ transplants. But there are 120,000 total patients on the donor waiting list and, on average, 22 people die every day waiting for a transplant, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

This gap exists mainly due to the limited supply of viable donor organs. Body tissues are made of cells, molecular signals and scaffold. The scaffold gives the tissue its structure and protects against the body’s forces. Currently, scientists do not fully understand the architecture of scaffolds to replicate them outside of the body, so doctors offer alternatives.

For example, in heart valve replacements, patients can choose to get a mechanical valve or a biological valve. Mechanical valves can last decades, but patients must take blood thinners for the rest of their lives to prevent clotting. Biological valves are made from cow or pig tissues and do not require lifelong blood thinners. But the immune system sees animal tissues as a threat.

“The presence of molecules called antigens in animal tissue flag it as foreign to the recipient’s body, instructing the recipient’s immune system to attack it,” Wong says.

There is one widespread workaround: using a chemical fixation process to mask these antigens in cow and pig tissues before a valve transplant. But this method works only as a temporary mask — like using cologne to cover body odor. This is why a biological valve lasts only 10 years in adults before they need to swap it out for a new one.

“If we can get biological valves to last 15, 18 or even 20 years, then no patient would really want to opt for a mechanical valve,” says Dr. Jeffrey Southard, an interventional cardiologist affiliated with the UC Davis Medical Center. “ViVita has been trying to work on a process to decrease inflammation and calcium deposits and the breakdown of these valves over time.”

ViVita accomplishes this through a chemical platform process, which extracts antigens from animal tissue to generate the scaffold that the immune system won’t reject. The company is starting in the heart valve market, but the platform technology can be applied to all tissues and body organs, Wong says.

Resultant scaffold product created by ViVita Technologies.(Photo

courtesy ViVita Technologies)

In 2013, ViVita Technologies won the 13th annual Big Bang! Business Plan Competition at UC Davis. To avoid a conflict of interest, the startup has been developing its products independent of the university (i.e. never using campus labs). They leased lab space only when necessary to keep costs low.

ViVita is trying to figure out how to pay for product development. They submitted a proposal for six-month $150,000 NIH Small Business Innovation Research grant. The award would support large animal testing of ViVita biomaterial toward heart valve product development. This funding would supplement the $750,000 ViVita is seeking in a seed round for product development and the commercialization effort.

Four years after launching ViVita, Wong understands that growth in this sector requires a lot of testing and time. “The necessary time and cost to validate the technology, and show that risk to patients is reduced as much as possible puts us in a completely different arena when it comes to seeking funding,” she says. “So often you hear it’s critical to move quickly, but in the medical device and life-science space, it’s a completely different timescale than for an app or high-tech startup.”

After this first phase, ViVita plans to expand with a product pipeline that includes heart muscle, small vessel, bone, liver and cartilage applications.

“The way they’re going about testing this is state of the art,” Southard says. “The science they’re putting together is very sound. They’re committed to making sure this works and I think if it does, it’s definitely going to be a big deal.”

Do you know an entrepreneur who has what it takes? Recommend their company for our “Startup of the Month” here.