It takes a hard yank to open the front door of Chili Smith Family Foods.

“Show that door who’s boss!” Steve Smith calls from behind a counter. “It’s old, like I am.”

Stepping inside the cluttered little shop is like entering a homey ranch house. A black-iron antique gumbo cauldron from Louisiana squats just inside the entrance, and two antique stoves and an antique ice box flank the small showroom. Stock pots, old coffee pots and pressure cookers are lined up on shelves near a community bulletin board and a mini-library on bean cookery.

It’s quaint, yes, but it’s also a well-organized storefront for the marketing and sales of 28 varieties of heirloom beans sourced from the Mohr-Fry Ranches in Lodi, which was founded in 1855. “Heirlooms are like people,” Smith says. “Each one is a little different, but on the inside they’re all good. They bond us together as humans.”

More than 40,000 varieties of beans exist worldwide, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, but only a small portion are commercially grown. A fraction of that are heirloom beans — a finicky, low-yield crop from heritage seeds passed down through generations of families and farms, and still not touched by genetic technology. They were eaten around campfires during the settling of the American West and helped sustain a generation through the Great Depression.

Heirloom beans are an antique that’s become hip, a long-forgotten staple being rediscovered by home cooks and backyard gardeners. They’re trendy because of their alluring connection to the past, and the ongoing foodie quest for novelty — in this case, something old that’s new again. And one local brick-and-mortar, Chili Smith Family Foods, has managed to build a business based on a renewed foodie interest in heirloom beans.

Chili Smith Family Foods opened its doors in April 2017. (Photo

courtesy Chili Smith Family Foods)

Banking on Beans

The reemergence of heirloom beans has been part word-of-mouth and part the proof is in the pot, as more home cooks and restaurateurs have discovered heirlooms’ departure from the relatively bland profile of bulk beans. Heirlooms have more pronounced flavors and textures, bolder colors, unusual shapes and sizes, and intriguing names — Tiger Eye, Jacob’s Cattle, Yellow Indian Woman, Lina Sisco’s Bird Eggs. Sill, they’re a specialty item because of limited yield and priciness. You won’t find them in Trader Joe’s or Raley’s, but Corti Bros. Market and Whole Foods sell a selection sourced from Idaho.

Credit Steve Sando, founder of Rancho Gordo New World Specialty Food in Napa, with helping bring heirlooms into the public eye through a reach and scope that are anomalies in the heirloom world, where most operations are much smaller. Sourcing from the Central Valley and Mexico, he built an heirloom bean dynasty that went from selling 300 pounds in 2001 to 500,000 pounds last year. Thomas Keller uses Rancho Gordo beans at his French Laundry in Yountville and Per Se in New York City, each with three Michelin stars.

Related: From Bot to Burger

Related: Hometown Spirits

“People now are more interested in quality and would rather have a little bit of something good that’s expensive, than 25 pounds of something bland and cheap,” Sando says. “There’s a place for both commodity beans and heirloom beans, but I think home cooks and smart chefs are getting it, that heirlooms are a great ingredient we’ve taken for granted. They have different aspects worth discovering.”

This renewed interest partly explains why Smith and his wife, Dale, were able to open a business in which heirloom beans play a central role. The hundreds of bags of beans on display at Chili Smith look like multicolored gemstones, shiny and vibrant. At $9 a pound, they’re nearly as precious. They’re an essential ingredient in the 750 pounds of chili that Smith make each month at an offsite commercial kitchen and sells frozen in containers at the store in a heat ’n’ eat model. Essentially, the business is a confluence of heirloom beans and a 170-year-old family chili recipe.

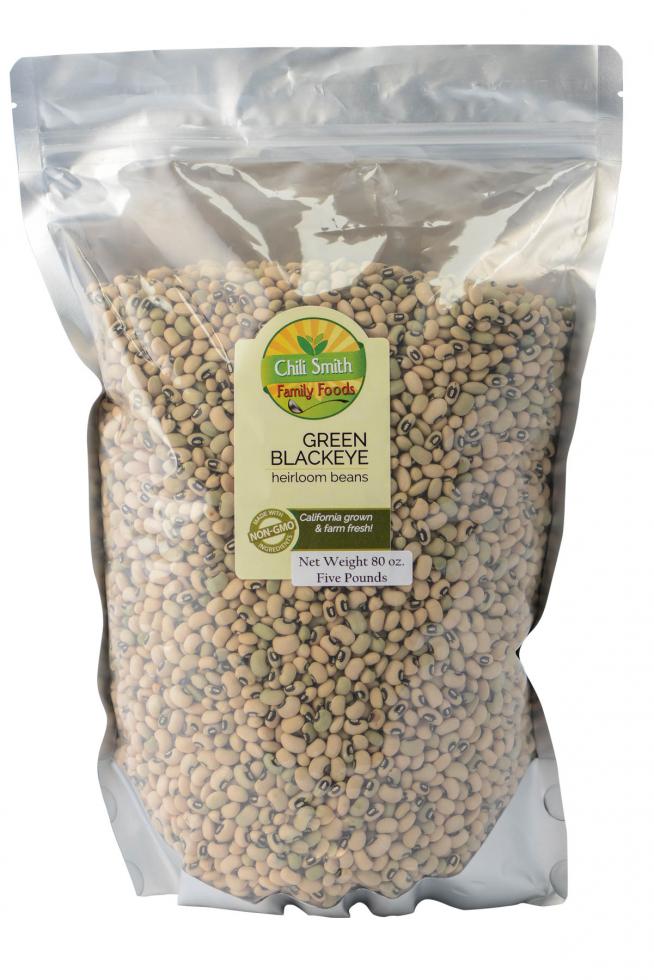

The Carmichael store sells 28 varieties of heirloom beans. (Photo

courtesy Chili Smith Family Foods)

The Smiths opened their store in Carmichael in April 2017 after 10 years of marketing heirloom beans and other products from their website and at farmers markets, food festivals and more formal events including the National Heirloom Exposition in Santa Rosa. Today, they sell beans to a loyal clientele of Northern California home cooks and chefs, website customers internationally, and restaurateurs and food distributors in a dozen major cities, including New York, Denver and Kansas City.

Michael Bacha, executive chef at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, is a longtime Chili Smith customer who serves 3,000 staff, students and visitors daily at his two cafeterias. “I love educating them about different varieties of beans other than good ol’ Southern black eyed peas,” he says. “We make hummus from Steve’s black garbanzos, and use (other varieties) in our plant-based salad bars as a protein source. Our customers love them.”

Around Beans Most of His Life

Smith has been around beans in one way or another most of his life. He grew up in Sacramento and Lodi, helping his parents run a mini-chain of restaurants called Mandy’s, which started in Chico and spread throughout the Central Valley, including Sacramento. They operated from 1960 into the 1980s.

The signature dish was chili from his maternal grandmother’s treasured recipe with roots in the Gold Rush era. “I made tons of chili for the restaurants, but didn’t pay much attention to the ingredients,” Smith says.

After college and his mother’s death, Smith left the family business to work for community/hotel developer Del Webb in Arizona and Nevada. He returned to Sacramento, worked at River City Petroleum, and then began studies to become a licensed Unity teacher and ordained minister.

During his career and travels, he often ran into past acquaintances and restaurant customers who would ask if his family still made the chili. But the recipe was presumed lost. Then, after his stepmother died, “We were cleaning out a closet in her home and found a box of old papers from the restaurant years,” Smith recalls. “We were able to piece together the recipe from handwritten notes.” Smith began making the chili and sharing it with friends and relatives.

Smith’s ministry studies took him on regular trips to Kansas City, and he would take along pouches of frozen chili to give to his instructors. One of them pointed out an article on heirloom beans in Bon Appetit magazine, which was Smith’s serendipitous eureka moment: “I figured heirloom beans would make a better chili, one that would be something different.”

Smith partnered with Mohr Fry Ranches and began marketing its heirloom beans online and at food events. “We handed out beans (and chili) and people wanted to know how to cook them. So we decided to do cooking classes, which is how the store came into play.” Chili Smith sells three kinds of chili, including the original beef and pork and a low-fat turkey version. The veggie chili contains 11 vegetables and four types of beans.

It also stocks housemade bean dip and barbecue sauce and other small-batch artisanal goods — a trio of honeys from local backyard hives, olive oils and balsamic vinegars from Fresno, rice from Chico, chipotle sauce from Lincoln, and herb-infused sea salts from Big Sur.

“We want to expand the cooking classes and get into catering, where we’ll cook chili and beans and cornbread in front of the guests,” Smith says. “It’s simple chuckwagon fare, but making things festive is what we do.”