Lee Pringle, founder and artistic director of the Colour of Music Festival, wants to increase the representation of people of color in orchestral and chamber music. Less than 2 percent of professional classical musicians identify as Black, and Pringle seeks to highlight the accomplishments of musicians of color not just to broaden the horizon of adult enthusiasts, but also to inspire children to see classical music as a style to study and enjoy.

Pringle’s traveling music festival, founded in Charleston, South Carolina in 2013, assembles Black chamber ensemble players from around the country to perform the work of Black classical composers such as Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges. The festival has taken place in six states and Washington, D.C.

After eight years, the Colour of Music has made its way to the West Coast. Billing itself as the Colour of Music Pétit, the four-night, seven-event festival makes its debut in Sacramento Nov. 10 and runs until Nov. 13. Each event features vocal and orchestral performances by musicians from around the world who identify as Black. Find out more about the Colour of Music and each event on the festival’s website.

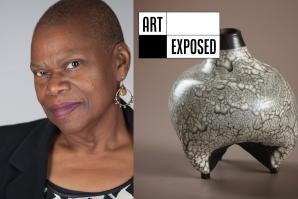

Lee Pringle is the founder and artistic director of the Colour of

Music Festival. (Photo by Jonathan Riess, courtesy of Colour of

Music)

Would you like to tell me the basics of the Colour of Music and why you decided to start the program?

In 2013, I started the Colour of Music in historic Charleston, South Carolina. (It’s) a very unique place to the American story in that 40 percent of all Africans that came through North America during the Atlantic slave trade, they came to the Carolina colony, and unlike the Europeans who came into Ellis Island … we were brought here not of our own choosing. And so it has a unique place in history, and I think it was the appropriate place to start something that totally changed the European construct of what classical music is, of course, coming as an oppressed people.

When these (musical) institutions were established, we were not included, nor did the colonizers intend for us to be included. So we’ve been fighting that battle of showcasing our unique history to the classical music genre dating back to when it was created in the 1600s. And I wanted to provide a platform for conservatory-trained, serious classical artists to perform the works that they study 10 and 12 years to perfect, but because of the complexity of the American orchestra system, we still represent less than 2 percent of all people that are on the American orchestral stages. So it’s the last water fountain post — Jim Crow civil rights, I often say — for Black people in the United States, and I can say abroad, because the same thing happens in Europe and the continent of Africa.

You touched on Europe. You’re using the (British) spelling of “colour.” Could you talk about the significance of that?

You know, ironically, when I worked with a gentleman who’s a dear friend who became my first graphic designer, I told him that I wanted to start this festival highlighting Black contributions to classical music, and I really didn’t know what to call it. But it’s funny that I was walking in a high-rent district area of downtown Charleston, and was walking past a store that had models on a billboard and the store was the United Colours of Benetton. I don’t even know whether they’re still in business. And of course, they used the European spelling of colour. And I thought that’s very unique because what it does is it makes it a global brand, as opposed to something that’s germane only to the United States.

And I thought that that would be a great way for people to look at the Colour of Music festival as a Black entity rather than an African American entity … because Black people permeate the globe. But here in America, we’ve put these distinctions on Black Americans being referred to as African Americans. I didn’t want to alienate Black people who came here as immigrants from various places on the continent of Africa, because they never will feel that they’re African American. They always feel that they’re their Black Africans. You understand what I’m saying? So that’s why we use the European spelling of colour, because … it’s also more of a global understanding of the word.

Let’s revisit that less than 2 percent figure. What do you think has contributed to that, either contemporary or historically?

Because of the complexities (of) the American story, we did not get any notoriety that we were even in the classical genre in the United States until when people started hearing the likes of Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Leontyne Price and others. … People just didn’t consider us to have an interest or have been in that art form, but we date back to the time of Haydn and Mozart and earlier. …

“I think people still don’t understand that those (musical) institutions were built for white people and never intended for Black people to be a part of the art form.”

A man by the name of Joseph Bologne (is) referred to as Chevalier de Saint-Georges, and he is considered to be the father of Black classical music globally … in addition to being a (colonel) in the French Revolution. … He was a master fencer, he was educated … with a classical education; the education that a James Madison or Thomas Jefferson would have gotten. But it was a unique dynamic. His mother was an African slave in Guadeloupe and his father was a white sugarcane plantation owner. So you can see this complexity of Black contribution to classical music with this (mixed-race person) being taught classical music and becoming a virtuoso violinist (and) composer. He wrote six operas. …

But when (America’s musical) institutions were being established, you had Jim Crow, it was post Reconstruction. … I think people still don’t understand that those institutions were built for white people and never intended for Black people to be a part of the art form.

The Grimbert-Barré Trio performs Nov. 12 and 13 as part of the

Colour of Music Festival in Sacramento.

I would imagine that part of this program is not just to celebrate the musicians that are already involved, but to perhaps show younger people with an interest in classical music that there are options.

Yes. I had elementary music in school and often say to people music has (taken) me places where I physically couldn’t go. … Music has something. … If a child takes up an instrument, be it piano, a stringed instrument or a brass instrument or percussion instrument, and they stick with it, it is something that helps them academically because most kids, if they have to learn an instrument, it’s total independent learning.

“The stats have shown kids who study music do better academically in math and sciences, because they learn something that the other children that are their peers don’t have.”

Your parents can’t teach you music unless they are music educators, but most people who take music, in particular private lessons, their parents are shoveling them into someone’s home. They get a 40-minute or 45-minute class once a week, and that helps them with comprehension. It helps them with reasoning skills, it helps them with logic, mathematical skills, subdividing, algebra, all those things are part of learning an instrument that puts children on an academic trajectory. The stats have shown kids who study music do better academically in math and sciences, because they learn something that the other children that are their peers don’t have.

We talked about the benefit to all children. But you know, the program is called the Colour of Music. What specific benefit would you see in children of color attending your programs while you’re here in Sacramento?

I came from a poor background. I went to Title 1 schools, and I often say that I never had a new textbook the entire time I was in school. I did skip 11th grade and went to 12. So I can account for those years. And, you know, this is applicable to poor white children as well as poor people of color, the Latino or Hispanic (children), where these things are the challenge. … So I think for Black students who are in underserved communities where their parents can’t afford private lessons, and they may not have a strong program in their school, seeing themselves represented on a chamber stage or an orchestral stage can totally change their lives, because most of them don’t know anybody who plays a classical instrument.

And so all those benefits that we talked about earlier, for that academic trajectory, those young Black kids, male and female, get to see themselves in a different light. And as you know, people and children dream of being things that they can see. … So that’s why I think it’s important, for Black children in particular, to see an all-Black ensemble because it can help them hopefully decide that “I want to do this, it’s fun,” and then they will get all these peripheral benefits academically that they do need to know about.

Can you talk a bit about why Sacramento was an appealing place for you to bring the program?

Really it’s because of former (Sacramento city) council member Larry Carr. Larry is a true visionary. … He understood, based on being introduced to me through a mutual family friend, that this could add to the cultural fiber (of) Sacramento. … He understood that music was one of those areas that not only could inspire children, but you could bring multiple ethnic groups and backgrounds together. We all love music, but we don’t always get exposed to the other cultures’ music, because of the way that the world operates.

So Larry Carr was the impetus for us coming. He introduced me to Mayor Steinberg and at the time, former city council member Alan Warren and Rick Jennings II. So they were the three people who said listen, we want to get behind this as city council members to showcase this to our constituents. And then of course, COVID came and we had to postpone it. But we initially were going to do this in May of 2020. And I was here the day that we shut down in March of 2020, and everybody had to shelter in place for several weeks. And then of course, the rest is history.

We’re talking about chamber music. We’re talking about orchestral music. These (can be) very large, collaborative projects. What does one do during the pandemic when one did have to shelter in place? For example, how did you personally cope with not necessarily being able to be part of a large ensemble?

Initially, we were devastated, because we realized our whole model was dependent on people gathering. And so the first thing we did was we qualified for some grants that allowed us to do some virtual events. And so I had to learn how to do post production behind the scenes, because we didn’t have any ability to get on the stage, and I became a quick master at video framing shots, basically being an art director and cinematographer with a videographer. …

And of course, George Floyd became a global tragedy not only just for America, but people around the globe resonated with it. And so that kind of put us in a different light. … And so I think, not only music organizations, but … sponsors and foundations started thinking, you know, we keep going to the same people to support, but we’ve never had a concerted effort to support Black arts institutions. … That brought that whole view of how Blacks are treated in the arts world compared to the majority population.

Edited for length and clarity.

–

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Art Exposed: Sarah Marie Hawkins

Multimedia artist Sarah Marie Hawkins uses a variety of methods

to tell not just her story, but the stories of many women.

Art Exposed: Deborah Pittman

A professional clarinetist broadens her creative output with

ceramics, writing, filmmaking, multimedia performances — and

puppets.

Art Exposed: Dan Herrera

Photographer and college professor Dan Herrera appreciates

the art of using older or alternative methods in his work; some

of his techniques date back 200 years or more.

Art Exposed: Binuta Sudhakaran

How this artist focuses on mindfulness over capitalism in her abstract minimalist paintings

Sudhakaran calls her work abstract minimalism, and she

applies paint to canvas in layers, creating an ethereal effect

that suggests movement and contemplation.