With the ubiquity of camera phones, it can be difficult for anyone beyond the pros to remember the era of film cameras, let alone methods of photography that required more delicate adjustments for a satisfactory result. But professional photographers still embrace older and alternative methods of photography and the unique results they can yield.

Photographer and adjunct professor Dan Herrera is one who appreciates the art of using older or alternative methods in his work. As a professor at Sacramento State, San Jose State University, Sacramento City College and American River College, some of Herrera’s courses instruct students in photographic techniques that date back 200 years or more.

Some of these processes fall under the umbrella of what’s known as “wet plate” photography, which encompasses tintype photography — a style of photography the average person may associate with the idea of 200-year-old photographs of very stern, often unhappy-looking people. Herrera’s subjects are modern-day, resulting in an intriguing combination of old and new.

Hererra’s interest in alternative photography includes not just the deceptively fast, 10-minute tintype process but also processes that use materials like coffee grounds and beets to produce arresting prints. Comstock’s spoke to Herrera about his methods and the philosophies behind them.

“It’s a one-of-a-kind thing that comes out of the camera, kind of

like a Victorian-era Polaroid,” says photographer Dan Herrera.

(Photo by Dani Padgett Watson, courtesy of Dan Herrera)

It is, yeah. Technology-wise, it’s basically the same. I’m using some newer things, like the camera that I use. Most of it’s made out of metal, and there’s some plastic pieces on it, whereas a true vintage camera would be made out of wood and brass. And I use plastic developing trays for some things. But the process is largely the same, where you take a blackened piece of aluminum — I use trophy plate, like if you’ve gotten a soccer trophy, and it’s got your name carved in it, it’s that material. I coat it with a solution called collodion, and then that gets dipped into a tank of silver nitrate. And then when those things combine, it becomes light sensitive. And then that whole thing goes into the back of the camera.

I take the photo while the person is sitting very still. And then that plate that was in the back of the camera gets developed. And that’s what I give to the client. So they’re getting the actual plate that the light touched. It’s a one-of-a-kind thing that comes out of the camera, kind of like a Victorian-era Polaroid.

We’re living in a time where people can be very fidgety, looking at their phone, looking at their Apple Watch. So is the process of actually getting a good photo of a person harder with this process?

Usually, when I sit down with a client, or even if I’m doing a street festival, and somebody is curious, and they want to sit down for a session, I explain to them how it works. You have to sit very still. And I usually explain there’s a reason why, when you look at old pictures of people from the 1850s, they look very stiff and usually very stern, and it’s because they’re sitting in the blasting sun for 10 to 15 seconds.

And the other thing that happens when I’m photographing somebody, and they are asking what to do with their face, I usually tell them to — I mean, smiling is cool if they can hold it for five to 10 seconds, but around second number three … people become very aware of their face, and then all of a sudden the smile becomes less authentic or something and when you look at the plate, you can tell that the person feels unsure of themself, maybe with this sort of plastic smile on their face. So I think a natural expression is usually easier to photograph. …

Dan Herrera coats trophy plate in collodion and silver nitrate to

make it light sensitive, and that plate goes in the back of his

camera. (Photo by Dani Padgett Watson, courtesy of Dan Herrera)

Usually when people seek out what I do, it’s because they understand that it is in an imperfect object, right? It doesn’t have the shine and the gleam as, say, Instagram does, where everybody’s very concerned about how perfect things look. There’s something that happens when you’re holding the actual object in your hand and you’re looking at all the imperfections on not only the plate, but you can see blemishes and out-of-place hairs and things like that. And the authenticity that that brings, I think still means something to people, which is why it’s still relevant.

That’s very interesting that you use the word authenticity, when people do have to sit still and be very conscious of the pose that they choose, which is actually a lot like Instagram in the way people are conscious of what they’re doing.

I use the word authentic, but you’re right, it is highly staged, right? So it’s not like capturing a candid moment. But I think the level of detail that these photographs provide, along with the idea that it’s in the moment, and it’s kind of unfiltered, that’s sort of what lends to the authenticity, even though the act of doing it is staged.

You’re taking modern photos with older methods. Some of those subjects, the people that you’re photographing … they’re exceedingly modern looking. What reaction do you get?

There is something cool that happens when you combine old and new stuff. … Photographing modern people in this older process is part of the charm of the series, photographing eclectic and eccentric looking people. … It sort of speaks to an older time, but it’s so bizarre, it has to come from now. And so there’s an interesting juxtaposition that happens where you start mixing, taking things out of time, I guess, and like having this anachronistic setup where I’ve got a modern person, but I’m photographing them in a way that they would have done in the 1850s and using a similar process.

What have you focused on in the last two years?

It’s been hard to connect with people and photograph people throughout the pandemic. And so I don’t work just in wet plate, I do several other alternative process ways of making images. And one of the ones that I’ve been most interested in is just using plant material. You can make prints with plants; they’re called photograms. But you can also make developer out of coffee, you can sometimes use blackberries or beets to make a photo emulsion called an anthro type. And so I’ve been really very interested in these sustainable processes, photo processes that are really accessible, really low toxicity. Not super bad for the environment.

Historically, photo is probably one of the worst offenders in terms of environmental toxicity, right? I mean, oil paints, for sure. But photos, probably the king of the toxic processes. And so I’ve always struggled with that a little bit, especially now when it seems like climate change and everything else is so critical. And I don’t want to be a polluter. … I think that’s one of the draws of these more sustainable processes.

So you were talking about blackberries and coffee. Coffee or coffee grounds?

Coffee grounds. That specific one is called caffeinol. … I think I have some images on my Instagram here I could just show you really quick to show you what I’m talking about. … So that one is made with beets (the pink prints), that one’s made with turmeric (the yellow prints). That one’s made with spinach greens (the dark green print).

Oh, I’m surprised by the spinach greens. I wouldn’t think that it would have quite that tone.

You basically extract the juices and the phenols out of the plant material, you add a little bit of everclear. And then you brush that onto the piece of paper. And then you use an oversized, negative or positive like a transparency to make the actual print. … I’m doing a direct print with that same negative using the juice.

That’s very cool. You can compost it when you’re done.

Well, exactly. Yeah. And the other thing that’s, for better or worse, is the piece is more ephemeral. After you make it, it doesn’t have the longevity of say, a silver print, a gelatin silver print, or a color photograph that comes off of your Epson printer. It’s more fragile than that. And so you can do things like spray it with a UV coating, preservative, to help keep it from fading. But if it sits out in the sun, it’ll fade. And so there’s something special and kind of romantic about that, of it being precious.

Do you know the relative life? I’m sure it varies based on the plant or product.

It definitely depends on the plant. And it depends on, is it sitting in a frame in the blasting sun, or is it sitting in a dark dresser drawer somewhere, right? And if it’s protected from light, it’ll last basically indefinitely, but if it’s sitting out in the sun, it’ll fade. But there’s not really a set timeline for it, because each print is going to be different depending on what plant matter you used.

And so each one prints out at a different rate too. Like, say, beet greens print really fast. Whereas the beets themselves, if you chop that up and use that to make out a reddish looking print, that usually will take a couple days to actually print out, so it’s very slow. And then sort of the trade off is, if it prints really fast, it’ll fade fast. But if it prints really slow, it’ll fade slower. So that’s really the only guideline that I can give students when they’re asking about the fading of stuff.

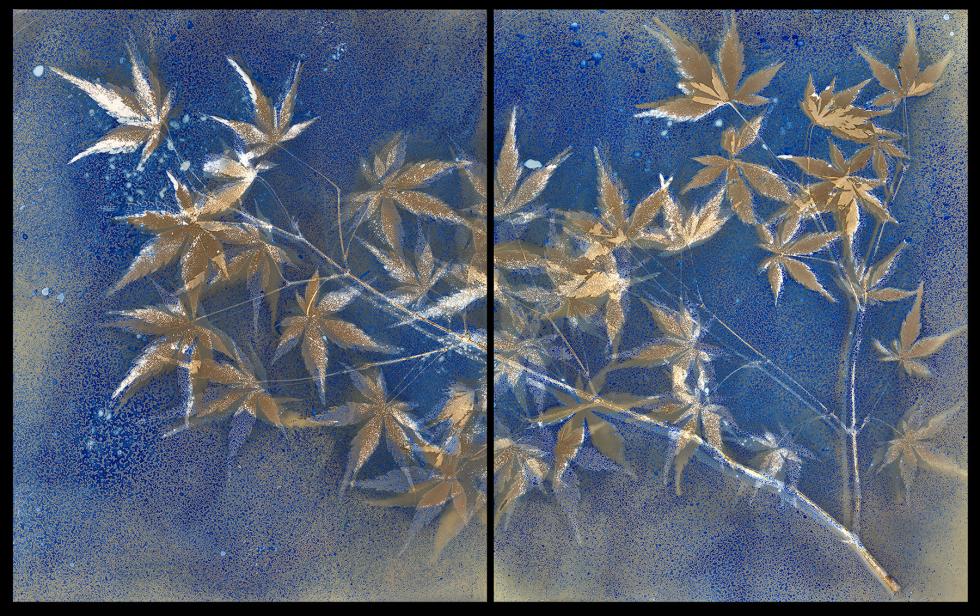

Dan Herrera works with plant-based photographic processes in

addition to traditional tintypes. (Photo by Dan Herrera)

When you were speaking, it was making me think of the preciousness of these plant based processes that fade faster versus the longevity of these wet plate processes, which are generally highly toxic, but they’re pretty bulletproof. I mean, there’s a reason why there’s examples that have been around for almost 200 years, because they’re super, super archival. … But that is sort of an interesting thing to think about, where different processes have different longevity to them. …

One of the cool things about photography right now is there’s so many different processes that people can draw from, to kind of express their vision, whereas something might not look good as a tintype plate. It might look excellent as one of these anthro type images. I think it’s a really exciting time to make photographs. …

As scroll fatigued as we all are, there’s something special about having a physical thing. It’s like the difference between meeting up with somebody face to face and having a conversation and liking their posts on Facebook. Even though, yes, the new tech makes certain things easier, it doesn’t disqualify or make the older tech or analog stuff bad.

I understand a little bit more about what you were saying, the authenticity of deciding what moment you’re going to preserve versus taking 1000 pictures, editing them so you look perfect, and missing the experience.

I don’t want to try to discredit the idea of what they call “spray and pray” when you’re doing an event. You spray a billion photos, and you pray that 10 of them work for your client. So that’s a perfectly fine and dandy way to do stuff. That’s kind of the way you have to do stuff now because people expect it. … I don’t think it necessarily detracts from the moment, but it’s a different kind of experience than, say, sitting down for one photograph. …

I have a joke: When I sit down with people, I always say, this will last longer than your Facebook stuff. I mean, where’s your MySpace profile? And that’s not even that old. That’s 10 or 15 years old, when people were using that. And that was what I used to look forward to on social media, I’d be like picking my top eight, you know, so stoked on it. And now there’s no need for that, you know, it’s not what is used.

“There’s something special and kind of romantic about” the

ephemerality of plant-based prints, Dan Herrera says. (Photo by

Dan Herrera)

But, you know, as precious as I thought some of those photos were that I posted at that time, it’s like, I have no idea where they are now. I couldn’t find them if I wanted to. But that one plate that I have with my son and my wife, that’s probably going to be something that I have until the day that I die. … It’s like the idea of the family photo album, the physical thick family photo album your mom would take out to embarrass you in front of dates. Now that’s your Instagram feed. …

I’m not trying to say I don’t like the new tech. I love it. I’m addicted to it like everybody else. But you know, there’s still something special about working with your hands and about the craft involved in making something that’s imperfect.

Edited for length and clarity.

–

Stay up to date on art and culture in the Capital Region: Follow @comstocksmag on Instagram!

Recommended For You

Art Exposed: Akira Beard

How painting saved this artist’s life, and how tattooing supports his work

Akira Beard recently became a tattoo artist so he could “go

anywhere, tattoo, make money while I’m there, trying to open up

doors of opportunity with my actual art,” he says.

Art Exposed: June Steckler

A painter and curator learns it’s easier to manage other people’s art and finds gifts in aging

June Steckler is optimistic about the Capital Region’s art scene

and her role in it as both artist and curator.

Art Exposed: Jupiter Lockett

A Sacramento artist uses his paintings to address race and social issues

Jupiter Lockett paints in a free and childlike manner, but

his subject matter focuses on the Black experience and is

intended to make the viewer uncomfortable.

Art Exposed: Octavio Valencia

A photographer talks about fashion, mental illness and a close encounter with Anna Wintour

Octavio Valencia has a secret identity. Or two.