Like no medical imaging system before it, the Explorer can capture a 3D picture of the entire human body at once. It seems like something out of a sci-fi movie, but the world’s first total-body positron emission tomography scanner is very real and currently running at UC Davis Health.

Developers believe this innovative device, which combines PET and X-ray computed tomography, could lead to many possibilities for cancer diagnosis and studies of blood flow, inflammation, immunological and metabolic disorders. It could also be useful for brain diseases, heart conditions and ailments involving multiple organs.

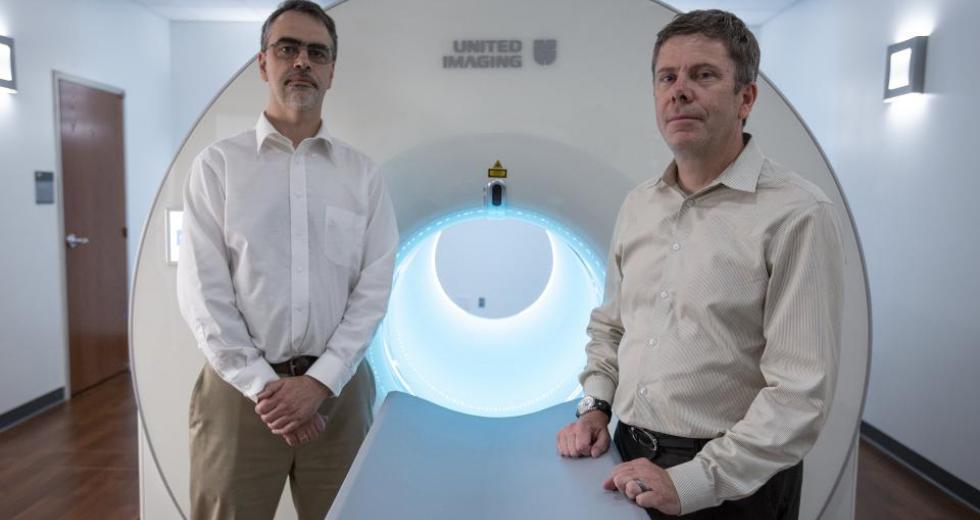

This total-body scanner came from an idea that began 14 years ago with co-inventors Simon Cherry, distinguished professor in the UC Davis Department of Biomedical Engineering, and Ramsey Badawi, chief of Nuclear Medicine at UC Davis Health and vice chair for research in the Department of Radiology. After receiving funding support from the National Cancer Institute and a $15.5 million grant from National Institutes of Health in 2015, the Explorer was built by UC Davis industry partner United Imaging Healthcare and installed in a specially prepared space on Folsom Boulevard in May 2020.

Comstock’s spoke with Cherry about the groundbreaking work that led UC Davis to name him and Badawi as among the recipients for the UC Davis 2020 Chancellor’s Innovation Awards.

Why did an invention like this take until now to be developed?

Probably the largest impediment was getting people in the field to believe this was a worthwhile endeavor, and that while the cost of such a system would be high, that the benefits would justify the cost. Certainly, it is easier to do now because of new technologies and increasing computer power than it would have been, say, 10 years ago. Nonetheless, it could have been done much sooner.

Are the doses of radiation comparable to traditional techniques?

It depends. The system has much high sensitivity and collects about 40 times as much signal from the body for a given radiation dose. So one of the nice things is you can choose how to use that extra sensitivity depending on the application. So, in some cases, you would choose to collect more signal and get better quality images. In another case, you may choose to reduce the radiation dose and collect the same signal we get with conventional scanners today.

A third option is to scan in much less time. Exactly how you trade off radiation dose, speed and scan quality depends on the medical or research questions and the patient population under study. You will make very different decisions in, say, an adolescent with a non life-threatening condition (where minimizing radiation dose may be the choice) versus in an elderly cancer patient (where maximum image quality to inform treatment may be the choice). The great thing about this system is that you have a very wide range of possibilities, ranging from scanning 40 times more quickly than regular scanners, imaging at 40 times less radiation dose than regular scanners, or collecting 40 times more signal than regular scanners.

The Explorer PET scanner, developed by scientists at UC Davis,

can capture a 3D picture of the entire human body at once.

How does lower radiation doses affect the results?

With the total-body scanner, we can get results equivalent to those on a regular scanner with something like 1/20th to 1/40th the radiation dose. However, if we use the standard radiation dose, we get much better images than with a conventional scanner. Again, the decision comes down to the medical or research question.

Did you have any challenges in the beginning when it came to pitching and fundraising?

Yes, it took roughly a decade to get the funding to build the first system. Our primary funding sources would be from federal research grants or by working with industry. We had many failures, as for a long time people were not convinced by the concept. However, now that the first system has been produced, there is great enthusiasm, with many conferences featuring dedicated sessions on total-body PET scanners, and many other researchers and other companies now working on this concept. Interest has really taken off in the last couple of years, attracting more funding into this area.

Would the general population be able to use the Explorer for screenings?

For screening to be successful, you want a low-cost test with very good sensitivity and specificity. The cost of the Explorer instrument is high, therefore, it is not likely that this is a good approach for mass screening. However, a more likely future role for Explorer might be in conjunction with other low-cost tests. For example, one can imagine if a simple blood test became available for cancer, then a follow up PET scan just in those few individuals with positive blood tests might be effective to determine where that cancer is located. However, this paradigm is hypothetical at the present time. The better use of Explorer at its present stage of development, in my opinion, is to deploy it in patients where PET scans can make a difference in their treatment.

How many people have been scanned at this point? How were they selected?

We have scanned over 600 people, and over 500 of these are clinical patients at UC Davis who would have had a PET scan anyway but have received their scan on the new Explorer scanner. These are selected from the referrals we receive for PET scans and based on physicians’ requests. The other 100 or so subjects are research subjects participating in trials. They may be referred to the trial through their physician, or in some cases we advertise for volunteers to participate and recruit from the community.

Have the clinical trials begun? How will they be organized?

Yes, we have about a dozen active trials using Explorer to study a range of disease processes. These include studies of various forms of arthritis, a study of a new way to image the HIV virus in HIV patients, studies of inflammation that occurs in multiple organs after a heart attack, studies of the involvement of multiple organs in patients with liver disease, and we’re currently planning a study to study immune cells in patients recovering from COVID-19. Each of these trials are initiated by a physician or scientist and recruit from patients at UC Davis and the local community. We also have trials focused on methodological development, for example advanced image processing methods, including artificial intelligence, that get us even sharper or clearer images or that lead to more quantitatively accurate results. We also have comparison studies going on against regular PET scanners to quantify the improvements.

Any interesting findings you didn’t expect?

Some of our most interesting observations have come from extremely fast imaging, where we have been able to (capture images in as little as 100 milliseconds) across the entire body for the first time, to watch the dynamics of the injected contrast agent (which we call a radiotracer) as they distribute around the body following injection. We are expecting we will be able to extract a lot of meaningful physiological information from the first few seconds of the scans, which was inaccessible previously.

On the clinical side, we are seeing just how different the dynamics of the imaging signal can be in different tumors across the body — again, something that could not be readily studied before because one could not image tumors in different locations (for example in the lung and liver) at the same time.

–

Get all our web exclusives in your mailbox every week: Sign up for the Comstock’s newsletter today!

Recommended For You

Great Expectations at UC Davis

University announces a $2 billion fundraising campaign

A wide range of projects and initiatives on and off the Davis campus are set to be funded by the campaign, called Expect Greater: From UC Davis. For the World.

Startup of the Month: RAIVES

Medical clip helps organize hospital room equipment

As a hospital assistant at UC Davis Medical Center, Tony Braham helps nurses lift and move patients. In other words, “We’re the muscle of the hospital,” Braham says, and his startup aims to help “the muscle” be more mobile.