In January 1848, six Mormon men bunked together in a small wood cabin along the South Fork of the American River in Cullumah, as the Nisenan named the land where they had lived for thousands of years, meaning “beautiful valley.”

The men, part of the U.S. Army Mormon Battalion, had traveled from Iowa to San Diego to fight in the Mexican-American War, which, fortuitously or not, was close to an end upon their arrival. The war allowed the victorious United States to acquire more than 500,000 square miles of Mexican territory from the Rio Grande to the Pacific Ocean. Undeterred, the men headed north to become laborers at John Sutter’s sawmill in Coloma, which supplied lumber for a settlement Sutter was building called New Helvetia — present-day Sacramento — after having secured a 48,800-acre land grant from the Mexican government.

The men kept journals, taking meticulous notes of the days’ events. That’s how historians know with certainty the very day, Jan. 24, 1848, that sawmill foreman James W. Marshall spotted the glisten of gold settled into the crevices of bedrock as he and his workers dug a water channel. Many years later, in a recounting of his life, Marshall said this:

(T)here, upon the rock, about six inches beneath the surface of the water, I DISCOVERED THE GOLD. I was entirely alone at the time. I picked up one or two pieces and examined them attentively. … I then collected four or five pieces and went up to Mr. Scott (who was working at the carpenter’s bench making the mill wheel) with the pieces in my hand, and said, “I have found it.”

“What is it?” inquired Scott.

“Gold,” I answered.

“Oh! no,” returned Scott, “that can’t be.”

I replied positively — “I know it to be nothing else.”

***

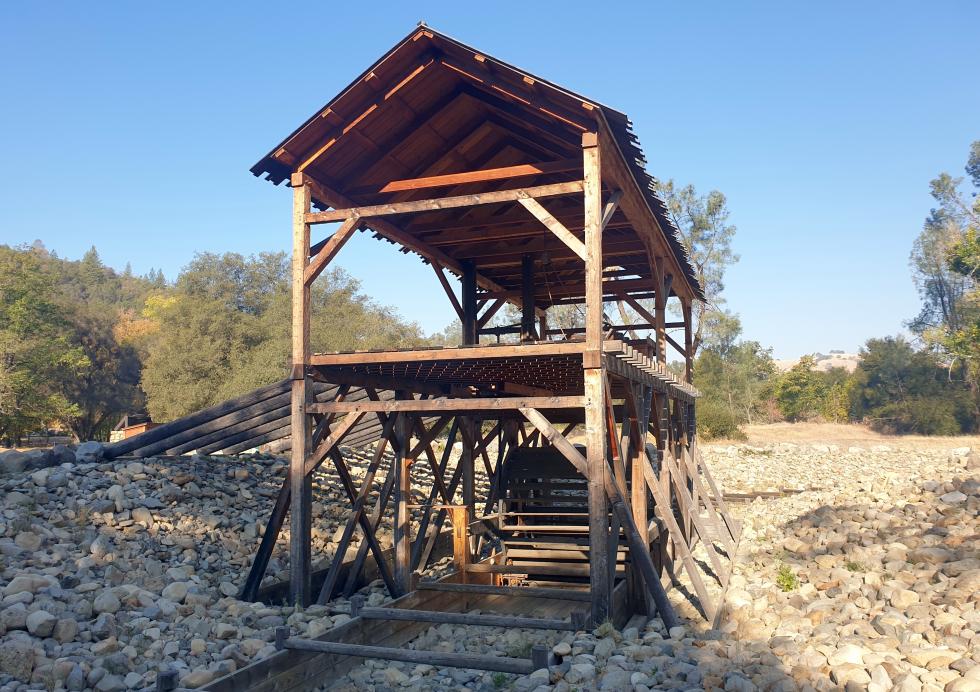

James W. Marshall was working at Sutter’s Mill, a water-powered

sawmill in Coloma, when he spotted gold in the South Fork of the

American River. A replica of the sawmill is part of Marshall Gold

Discovery State Historic Park. (Photo by Sena Christian)

Shelly Covert has loved harmony since her choir days at Nevada Union High School in Grass Valley, although her musical side was ingrained even before her teenage years by her father, a musician who played with local legends and whose bands sometimes practiced at her childhood home.

As Covert grew older, one of her father’s bandmates taught her the bassline to Santana’s version of “Black Magic Woman.” “It started with me just playing a few songs, then a whole set,” she says. She had earned her place in the band.

For more than three decades, Covert has performed on stages at weddings, bars, wineries and pubs throughout Nevada County. She is the lead singer and bass player for the rock band UnderCover. Her favorite band is a toss-up between Guns N’ Roses and Heart, whose lead singer Ann Wilson is her favorite vocalist, and she will take any chance to belt out a cover of “Barracuda.” “Back in the good old days,” she says, before the coronavirus pandemic put a halt to live shows, “I used to just play music. I’m not doing much anymore, which is a very strange and interesting life arc.”

Covert now spends her days following the path of her mother and grandfather, who long advocated, unsuccessfully, for the reinstatement of federal recognition of the Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe, which had been recognized in 1913 and then terminated in 1964 as part of the California Rancheria Termination Act, several laws Congress passed in the 1950s and ’60s. Without recognition, her tribe isn’t eligible for federal programs for housing, education, health care and economic development. It also means the tribe’s voice isn’t always considered on issues of importance to its members.

“Because we’re not federally recognized, we don’t have that big voice that’s automatically at the table, with required consultation on a government-to-government level like other federal agencies, so I feel like I’ve been finding creative ways to make things happen,” says Covert, spokesperson for the Nevada City Rancheria for about the past decade and executive director of the nonprofit California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project, founded in 2015 to “preserve, protect and perpetuate Nisenan culture.”

In 2018, as the result of being at the right place at the right time and some creative thinking, CHIRP acquired 32 acres of land along Deer Creek, or what the Nisenan call Angkula Seo, not far from downtown Nevada City. The nonprofit Sierra Fund has been instrumental in the project, in part by securing a grant from the California Natural Resources Agency for the land transaction. The grant limits that the land, called the Nisenan Cultural Reclamation Corridor, only be used for open space, recreation, habitat and cultural protection, in perpetuity. A new segment of the Deer Creek Tribute Trail will go across the property, which is on the former site of the Champion-Providence Mine — adjoining mines built atop an old Nisenan town.

The tribute trail is moderately traversed, and a weekday morning will find dog walkers, trail runners, clusters of teenagers and others on the route; many are locals, but some are out-of-towners who can make an easy day trip from Sacramento or the Bay Area. Millions of visitors pay homage to the Sierra Nevada each year, coming to hike, whitewater raft, ski, boat and fish, and maybe eat in an old saloon transformed into a modern restaurant, or shop for antiques or vinyl records in a historic gold rush town. Many guests stay at mom-and-pop hotels or at campgrounds, able for those few nights to gaze into a star-studded black sky framed by dense groves of pine, sequoia, cedar and oak trees.

And pay they do, contributing about $3.6 billion in economic impact annually and supporting 36,400 tourism jobs in a place where some 600,000 people live. The region, which covers more than 25 million acres, includes about half of California’s forests and supplies most of its drinking water. It sustains many animal and plant species, supplies roughly half of the state’s annual timber yield, and produces most of its hydroelectric power. But all of this could be at risk if the environmental and humanitarian damage of the past aren’t remedied.

Today, an estimated 47,000 abandoned mine features — including underground tunnels, old support structures, shallow pits and other hazards — litter the Sierra Nevada. Most are a remnant of the gold rush that ushered in a new industry and a mass migration of more than 300,000 people from 1848 to 1855. The prospectors dreamed of riches and engaged in activities that would leave behind a 170-year (and counting) legacy of scars.

Over the past two decades, a coordinated effort focused on science and policy, education and awareness, and an entrepreneurial approach to workforce development has been underway to come to grips with this lasting legacy. These efforts might now be at a tipping point, helped, however unfortunately, by California’s recent massive wildfires and how it is once again in a drought, which show the urgency and importance of restoring the health of the Sierra Nevada.

A Divine Right

Earth is a gold miner’s paradise. Hot water and pressure beneath the planet’s surface commingled to create gold in the Earth’s crust, distributing the precious metal widely all over the globe. Treasure seekers can find gold as lodes formed in cracks in the Earth, or as placer deposits, loose gold collected in sand or the gravel of riverbeds. Gold is heavy and settles at the lowest point it can go. Untarnishable, gold can also be pressed thin and shaped into multiple forms. It’s no wonder gold has been prized throughout human civilization.

But the mineral carves a dirty path on its way to consumers. California’s gold rush “left scars on the surface,” says Elizabeth “Izzy” Martin, the CEO of The Sierra Fund, based in Nevada City. “Sometimes you’ll see in the middle of town just a big open field,” she says. Mining that occurred in these places was a messy and disruptive process that left behind hazardous levels of contaminants like lead, mercury, cadmium, asbestos and arsenic. “Sometimes the right thing is to take contaminated land and seal it in with a parking lot,” Martin says. “I’m a lifetime environmentalist, and sometimes the right thing to do is to put in a parking lot.”

(California’s gold rush) left scars on the surface. … I’m a lifetime environmentalist, and sometimes the right thing to do is to put in a parking lot. … (For a century and a half, we) had not really come to grips with the size, the magnitude of the problem leftover from the mining era.

ELIZABETH “IZZY” MARTIN CEO, The Sierra Fund

Although Indigenous people had, since prehistoric times, modified the landscape and caused widespread ecological change, the arrival of Europeans and Americans for the gold rush brought a much more invasive level of alterations with the construction of dams, permanent manipulation of rivers, clear-cutting of old-growth trees and an ill-advised practice of fire suppression that makes these forests ripe for wildfires, especially when compounded by climate change, which means more heat waves, decreased snowpack and drier conditions among other impacts. This was all initially done in service of the mining industry and then the railroad and timber industries that soon followed.

For a century and a half, “(We) had not really come to grips with the size, the magnitude of the problem leftover from the mining era,” says Martin, who moved to Nevada County in 1986 when she and her then-husband bought a farm in Penn Valley. She moved to downtown Grass Valley in 2005. Beneath her house is part of Empire Mine, with mine shafts that stretch 367 miles underground. Empire Mine, considered one of the largest and richest hard rock gold mines in California, produced an estimated 5.8 million ounces of gold during its operations from 1850 to 1956. The former site of Empire Mine is now a state historic park.

Mining caused irreparable damage not only to the natural environment but also to Native Americans. Throughout what is now California, there were an estimated 350,000 Indigenous people, speaking at least 64 languages, before Spanish colonizers began arriving in the 1500s. By the time gold was discovered, the Indigenous population had dwindled to about 150,000 — a population quickly decimated even further as miners raided the Indigenous people’s villages, killed, or kidnapped and enslaved them, among other things.

“The whole story of genocide with the American Indians in California really is not common knowledge,” Covert says. Her tribe, the Nisenan, historically lived in the American, Bear and Yuba river watersheds, between the Sacramento River and Sierra Nevada. Although the tribe had long managed to avoid the reach of Spanish and Mexican colonizers, European fur trappers encroached on their territory in the 1820s, and in 1833 caused an epidemic that killed at least half of the population. An estimated 13,000 Nisenan lived in what is now Nevada County prior to the gold rush. There are about 150 members of the Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe today.

At the heart of this devastation was the 19th-century American mindset of Manifest Destiny. Settlers felt a divine right and duty to expand across North America, convinced that what they encountered along the way was theirs for the taking. “There was a sense that this was their land,” says Rich Gordon, a Sierra Fund board member and retired California State Assembly member. “They disregarded the Indigenous people … who had been protecting and maintaining the land and the resources. These new immigrants came in and saw the resources as something to be used and not something that you lived with.”

“There was a sense that this was (the settlers’) land. They disregarded the Indigenous people … who had been protecting and maintaining the land and the resources. These new immigrants came in and saw the resources as something to be used and not something that you lived with.”

RICH GORDON Board member, The Sierra Fund

Hundreds of years ago, Native tribes practiced what today is called natural resource management, tending the landscape to benefit people along with the needs of the water, soil, air, plants and animals. In contrast, the immigrants used any possible technique to, as Gordon says, “extract gold from the landscape at all costs.”

And all of this happened not solely because of the “eureka!” moment of 1848, but with a discovery made years earlier, and not in the shallow edges of the American River of Cullumah, but buried underneath the Earth’s surface more than 100 miles away in the Coast Ranges that held huge deposits of another heavy metal — one that would subsist long after the treasure chest of the gold rush had been emptied.

Quicksilver Abounds

Once a farmer, James W. Marshall lost his livestock when he left his ranch for a year to fight in the Mexican-American War and returned to a job at Sutter’s Mill in 1847. Upon Marshall’s discovery of gold the following year, he and his boss agreed to keep it secret. But it wasn’t long before Sutter was bragging about the discovery. Sam Brannan, a Mormon elder and newspaper man who ran a general store at Sutter’s Fort, couldn’t keep quiet either once he saw the precious metal himself. While in San Francisco in May 1848, he reportedly “paraded the streets waving a quinine bottle full of gold, shouting, ‘Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!’”

Aspiring miners arrived by the thousands, setting up settlements and digging for riches, which rarely panned out for the individual prospector. Major mining conglomerates soon pushed them out and took over the increasingly harder search for gold. “After about six months, all of the easy-to-find gold that was on the surface and in the riverbed had been picked up,” Martin says, “so the miners started to have to be much more aggressive to get to the gold. … They started to develop new mining techniques, a very destructive technique that was really invented here in California called hydraulic mining.”

Miner Edward E. Matteson is considered the method’s inventor, first using it near Nevada City in 1853. This method used high-pressure jets or cannons to shoot a powerful stream of water to dislodge rock material and remove trees, rocks, turf and dirt, anything that stood in the way of the gold; the soil, sand and gravel washed down a series of sluices, which caught the heavier materials that contained the gold (the muddy waste tailings were washed into waterways). Hydraulic mining required lots of water. Trees were cut down, rivers dammed, streams and creeks rerouted to mining sites to feed the hydraulic-mining beast. This method was “incredibly disturbing to the landscape,” Martin says.

Hydraulic gold mining also required mercury, then commonly known as quicksilver, and there was plenty of it to be found not too far away, because before the discovery of gold came another important discovery: mercury mines in the Santa Cruz Mountains. California’s Coast Ranges had massive deposits of the heavy metal, an area the U.S. Geological Survey describes as “among the most productive mercury districts in the world.”

Mercury was used in the separation of gold from rock: Gold dissolves in mercury, and then the solution is boiled, vaporizing the mercury and leaving the gold behind. Mercury was especially prevalent with hydraulic mining. According to the USGS, “Mercury was used to enhance gold recovery in all the various types of mining operations; historical records indicate that more mercury was used and lost at hydraulic mines than at other types of mines.” Court injunctions began restricting hydraulic mining in 1884, with North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company at the center of lawsuits against excessive debris and damage to farmland. (The site of North Bloomfield’s largest mine, Malakoff Diggins, is now a state historic park.)

Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park in Nevada County was the

site of one of the largest hydraulic mines in California. (Photo

by Carly Cornejo)

By 1852, the gold rush had peaked, although mining continued. These operations had become highly industrialized, the majority of individual miners lived in squatter conditions and failed to strike it rich, and the price of gold had dropped significantly. “When the price of gold, which had been fixed by our government at a very low level, was just too low, the miners basically walked away from their haul without doing anything to reclaim them, leaving behind these mines-scarred lands,” Martin says. In addition to the physical hazards of old mines, contaminants like mercury seep out of these sites and wash down hillsides and in waterways.

The dangers of mercury exposure weren’t really understood until a century after the gold rush, when in 1956, a 5-year-old girl in Minamata, a coastal city in Japan, had trouble walking and speaking and suffered convulsions. This girl became the first official case of Minamata disease, a neurological syndrome caused by severe mercury poisoning.

The Chisso Corporation’s chemical factory had been releasing methylmercury in its industrial wastewater, which emptied into Minamata Bay. The discharged toxin accumulated in the fish and shellfish consumed by villagers. The poisoning affected children most, but fetuses exposed in utero had horrific birth defects. “I remember seeing pictures as a child and believing that they were victims of the nuclear bomb in Hiroshima,” Martin says of the sick children. Mercury is now understood to be one of the most toxic metals found in the environment and linked to “toxic effects on the nervous, digestive and immune systems, and on lungs, kidneys, skin and eyes” in humans, according to the World Health Organization.

More than 26 million pounds of mercury were used in hard rock and hydraulic mining during the gold rush, and much of it remains in the region’s upper watersheds. Mercury is a stubborn little bugger. The neurotoxin, scientists say, will linger in the environment for 10,000 years.

Cleaning a Dirty Past

The time had finally come to address these lasting implications. In 1975, the California Legislature passed the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act to curtail the environmental harm caused by the industry. The Sierra Fund worked with then-Gov. Jerry Brown to pass two bills in 2016 reforming the SMARA. Brown had signed the original bill into law during his first tenure as governor, but “it’s not been enforced, and it’s like 30 years later, and he’s just livid, and he’s like, ‘We’re reforming this thing from top to bottom,’” Martin says.

Martin had joined The Sierra Fund in 2003, two years after its launch, with a mission to “restore ecosystem resiliency and build community capacity.” In 2004, as an outgrowth of the nonprofit’s advocacy, the Legislature established the Sierra Nevada Conservancy. Headquartered in Auburn, SNC covers 22 counties (it does not service the Tahoe basin, which has its own California Tahoe Conservancy, established in 1985) and is divided into six subregions with staff in each area involved in more than 30 collaboratives. “In that way, those members of our team really are able to sort of live and breathe, if you will, the work, the needs, the issues and the opportunities that are locally based,” says Executive Officer Angela Avery.

By mandate, SNC focuses on issues including land conservation and restoration, water and air quality, wildfire risk, economic development, and recreation and tourism. The funding-based agency partners with other government agencies, private-sector companies and nonprofits to address shared goals. It is this coordinated and collaborative approach that has proven effective at tackling the Sierra Nevada’s complex, interconnected challenges, Avery says. In other words, as Martin describes it, these are not “random acts of conservation.”

One example of this collaborative approach is the $8 million water-quality cleanup of Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park in Nevada County, “the mother of all hydraulic mines,” Martin says. A 2-mile-by-1-mile mine pit discharges mercury-laden sediment, concentrating in water bodies downstream, specifically the Yuba River. The Sierra Fund began working on the project in 2011 with a grant from SNC, and later Patagonia, Teichert Foundation and Department of Water Resources funded project research.The Sierra Fund handles the water assessment and maintains the gauge that measures discharge at the site every 15 minutes.

Many old mines are problematic because they contain toxic waste materials that run off and collect in reservoirs, harming water quality, accumulating in fish and entering the food chain. Not insignificantly, they also impact water storage capacity. California’s nearly 1,500 reservoirs have lost an estimated 1.7 million acre-feet of storage to sediment, according to a 2009 report. “The state keeps talking about, ‘Oh, we need more dams, we need to build more dams to hold water,’” Martin says. “Well, that’s great. ‘My house is really dirty. Forget it. I’m not cleaning it. I’m just gonna go build myself a new house.’ So we started to say, ‘Hang on, before we keep building new houses, how about we go and see if we can restore some of this capacity?’”

California Water Resources Control Board identifies more than 130 reservoirs as mercury impaired. One of those is Combie Reservoir in Meadow Vista in Placer County. In 2018, Nevada Irrigation District began a pilot project to remove mercury and sediment in the lake, which supplies water for irrigation, drinking, recreation, and hydroelectric power for consumers in Placer and Nevada counties.

The Nevada Irrigation District worked with several partners on a

project to remove mercury and sediment in Combie Reservoir in

Meadow Vista. (Photo courtesy of NV5)

The project used a unique suction dredge and centrifuge process to move sediment into a holding tank and separate the clean sediment from the mercury. The removed sediment must be free of mercury and beneficial for other applications, possibly as a road base for construction. “We had to come up with an innovative way to not only extract the sediment from the reservoir but to monitor and ensure that our systems were not degradating the water quality and the invertebrates and the aquatic systems at the same time,” says Greg Jones, NID’s interim general manager.

The team figured out a cost-effective and environmentally friendly process. “(We) can tell where the mercury is, and we can ensure that the sediment we remove is free of mercury and is actually just as good and can go out in your backyard garden,” Jones says. NID’s project is helping establish best practices for other water purveyors.

In terms of how humans are exposed to mercury, contaminated fish is the main way this can happen. Mercury settled in dirt isn’t very dangerous — “you can grow tomatoes in it,” Martin says — but upon entering water, it gets into the bottom of the food chain and biomagnifies. “So, 10,000 little sulfur-reducing bacteria get eaten by one bug, and that one bug gets eaten by a bigger bug, by bigger fish, and pretty soon you get to a … bass or a rainbow trout, there’s so much methylmercury in that fish’s body that it’s actually dangerous for humans to consume,” Martin says. “That’s the situation we’re in here in the gold country.”

On one side, Martin says, people argued that “nobody in the Sierra fishes. Those are just a bunch of catch-and-release Sierra Clubbers.” But between 2009 and 2016, her organization surveyed 374 anglers at 14 mercury-impaired water bodies and found that 43 percent planned to eat their catch and of those, 68 percent planned to also feed it to their families, says Alexandria Keeble-Toll, administrative director of The Sierra Fund.

In 2015, the organization launched an annual volunteer Post It Day event to post fish consumption advisories. They have posted advisory flyers at more than 125 locations at 25 water bodies in five watersheds. Keeble-Toll says sharing information about safe fish consumption has become even more critical during the pandemic. “We have noticed, and heard anecdotal reports from others working on this issue, that there has been an uptick in subsistence fishing since last March (2020). … As COVID has encouraged outdoor recreation as a safe diversion, there just seem to be more families interested in fishing.”

Besides eating fish, dust exposure to toxins is another concern. During the gold rush, gold may have been king, but miners also dug up silver, zinc, chromite, clay and stone, and brought up giant rocks loaded with naturally occurring lead, arsenic and asbestos that had been safely buried beneath the surface. Utilizing these materials for mining resulted in leftover waste later repurposed for things such as trail material, road base or rock base for play yards.

The Sierra Fund has tested trails on public lands built from abandoned mine materials — some had good systems and others were very dangerous. Martin gives the example of popular bike trails in Foresthill laden with asbestos fibers; while walking on these trails doesn’t pose a significant threat to human health, stirring dust up with recreational activities like mountain bikes or all-terrain vehicles can increase the possibility of exposure.

The organization has also become a trail builder, as shown by its role in the Deer Creek Tribute Trail in Nevada City. Dating back to 2005, this $2.6 million multiphase effort to create what will be a 9-mile route really gained traction in 2010 when The Sierra Fund came onboard as project manager. Martin’s group acquired a grant of nearly $740,000 in 2012; $600,000 went to the seller of the 32 acres in 2018 and the rest paid for parcel surveying, assessment and lab testing results, among other tasks.

Along the tribute trail, there are two bridges. One honors the Nisenan who once lived in the area, and another recognizes the Chinese immigrants who labored in the mines and later on the railroads that helped build California to what it is today.

Thinking Holistically

Many of the millions of visitors to the Sierra Nevada each year may not realize how the region, for all its beauty, is suffering. But that recognition is growing — California’s massive wildfires of recent years have made it impossible to ignore.

In 2018, voters passed Proposition 68, which authorized $4.1 billion in bonds to fund environmental restoration and conservation and outdoor recreation investments, and includes projects to mitigate the impacts of natural disasters such as wildfires. With a record fire year of more than 10.3 million acres burned in 2020, “it was sort of impossible for the administration now to escape the urgency of addressing California’s forest health problems,” Avery says. “We’re seeing broad-based consensus that California really needs to act decisively in protecting rural communities and the state, generally, from these fires and the impacts of these fires.” In January, Gov. Gavin Newsom proposed a $1 billion forest health package. In April, Newsom signed a $536 million wildfire package.

Embracing tribal ecological knowledge has proven critical in efforts to reduce wildfire risk. This approach includes guidance on things such as meadow restoration (damaged by mining and, later, farming and ranching), prescribed fire and selective thinning of overgrown areas — as opposed to the act of fire suppression instituted by the arrival of Europeans and Americans. “With suppressing fire, we changed its nature, and we can learn now from the Indigenous people who did prescribed burning. And they would go in and use fire to clear out the underbrush, clear out the smaller trees, allow the larger trees to grow stronger and taller,” says Gordon, who also is president of the Sacramento-based California Forestry Association. “The big learning for me has been the history lesson that we need to listen to the Indigenous people who understood that you live with your natural resources, not that you use them.”

Martin says the wildfire-oriented projects present an opportunity for also addressing the legacy of mining simultaneously. “How about while we’re out in the forest — because now everybody realizes the forest is really, really screwed up in this era of clear-cutting and followed by an era of fire suppression — you’re out in that forest anyway, and you see that there’s an abandoned mine. You can (remediate it),” she says. “You can take the mine tailings and reroute the creeks around them instead of through the middle of them. You can chip the trees and brush (and) put it on these denuded soils, which were very erodible because they were power-washed away 100 years ago.”

Avery agrees with the need for a holistic approach. She says the focus is also on resolving policy impediments to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration and an entrepreneurial approach to dealing with the biomass that results from wildfire-reduction projects. “We need to figure out how to increase the amount of wood processing infrastructure that allows us to deal with the small woody biomass that we know needs to come out of the forest,” Avery says. One of the organizations SNC partners with, Calaveras Healthy Impact Product Solutions, is working on precisely that.

Administrative staff of Calaveras Healthy Impact Product

Solutions meets with a U.S. Forest Service biologist for an aspen

stand regeneration project. (Photo by Thurman Roberts)

Meanwhile, the grappling of issues in rural communities, beyond wildfires, has entered the national spotlight. In March, President Joe Biden announced his $2.3 trillion plan to transform America’s infrastructure that includes $16 billion to clean up abandoned coal, hard rock and uranium mines, and plug old oil and gas wells. According to the administration, “Many of these old wells and mines are located in rural communities that have suffered from years of disinvestment,” and these efforts will put hundreds of thousands of people to work.

A New Economy

In 2004, as Martin was taking the helm of The Sierra Fund and Covert was playing in her band, Steve Wilensky had just been elected Calaveras County supervisor on a platform of environmental restoration and economic development as symbiotic. “This was, at the time, somewhat novel,” says Wilensky, who held the seat through 2012. “The ‘timber wars’ around here were quite fierce.” The interests of environmentalists and logging companies were intensely pitted against each other.

Most of the area’s lumber mills had shut down by the early aughts. While environmentalists at first celebrated their legal wins, unforeseen consequences soon surfaced. “We went from a relatively prosperous but resource extraction-based economy to a devastated mess that was an environmental disaster,” Wilensky says. “When you log heavily and then do nothing for decades, you wind up with a forest that is not a natural forest.” New tree growth was young and evenly aged, and the forest became overgrown with fuel, both factors that increase wildfire risk.

“Despite that environmental groups had been successful at stopping bad stuff, they were not successful at getting good things to happen because it was primarily defensive,” Wilensky says. Meanwhile, former loggers and mill workers wanted their jobs back, but there were none. “Around here, there were communities that had been completely devastated — the social mayhem index was off the charts,” he says. “Meth and our children were our biggest exports.”

Sam Simmons (in white helmet) and Craig Christensen (in orange

helmet) are two of the Washoe crew leads of Calaveras Healthy

Impact Product Solutions. (Photo by Thurman Roberts)

Out of those conversations came Calaveras Healthy Impact Product Solutions in 2004, a nonprofit based in Calaveras and Amador counties, led by Wilensky, which hires and trains people to do field restoration work, such as tree thinning, invasive plant removal and prescribed burns. The group secures contracts with landowners to do this work. Sixty percent of California’s 33 million acres of forest land is publicly owned; private landowners such as families, tribes and timber companies make up 40 percent. CHIPS employs 50 people from Yosemite in the south up to Chico in the north. The majority are Native Americans from eight tribal groups.

“It’s a pretty comprehensive program that is doing really amazing work connecting tribal knowledge and tribal cultural practices but also working in today’s world where they’re creating long-term sustainable work,” Avery says. Efforts are underway to establish at least five similar groups throughout the Sierra Nevada by later this year.

Additionally, CHIPS bought an old mill site and has a power purchase agreement to produce renewable energy from wood waste. The organization is exploring other value-added products that can be derived from the biomass material. “And that sort of completes the cycle,” Wilensky says.

By 2020, CHIPS had secured $5.5 million in grants and was preparing for its big expansion year when the pandemic hit and caused delays, which it is just now coming out of. A much deeper challenge remains, though — pandemic or not. “Recovering forests and watersheds has clear prescriptions and good science,” Wilensky says. “Recovering communities that have been left for dead for two generations is a much harder thing. How do you gear up a workforce? How do you get people off their addictions? How do you get people who are in poverty transported to work sites far away from where they live?”

But it can be done, and he points to the success stories, including work with the Paiute community in Mariposa Grove in Yosemite Valley who had been removed from their ancestral homeland. CHIPS employs four women as a crew there to help reroute trails around sacred and cultural sites, collect native seeds, remove invasive plants, and do prescribed burns.

Thurman Roberts, CHIPS program facilitator, agrees that engaging tribal communities can be a heavy lift. “There’s always going to be bumps and growing pains with anything that’s going into a community that’s been long devastated with high unemployment rates, drug and alcohol abuse,” says Roberts, who was hired by CHIPS in 2018 as a field crew worker.

Roberts is of the Washoe people from the Hung A Lei Tí reservation on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, south of Tahoe. He attended Humboldt State, staying for 15 years in the North Coast before a yearning to be closer to his aging parents and a desire to help his community pulled him back home. His job now involves outreach, project management, coordinating with government agencies and workforce development.

CHIPS — with its triple-bottom line framework — can be the meeting point for those working on the legacy of mining, forest health, rural economic development, and efforts to restore tribes to their ancestral lands, or erase the pain of the past. Roberts talks about West Point, a place in Calaveras County ravaged by methamphetamine. “Once all the mills shut down, a lot of people reverted to drug use,” Roberts says. “When I explain my situation with Native communities, they say, ‘Yeah, we have the same thing going on within disadvantaged non-Native communities.’” This is where he sees common ground.

“I think about family lines and generations, and having a story of a place that they can tie to of being home or being grounded and connected — that just goes beyond any ethnic group experience,” he says. “That needs to be preserved, not only to keep those stories and the connection to the Earth, but also to show that we’re part of something bigger.”

Ties That Bind

Covert and Martin can’t wait until the day the pandemic eases and they can safely sit down together in Nevada City — the town where they both have their offices — to catch up over drinks. They always have plenty to talk about, what with their work on the Deer Creek Tribute Trail and their love of music. Martin is a “classical-musician-turned-Irish-musician” who sings and plays piano, harp, pennywhistle and Irish flute in Nevada County Kitchen Sessions, a Celtic band.

For now, though, they’re focused on the next phase of the tribute trail, specifically building the segment on the acreage along Angkula Seo. Through it all, this work must remain tribally centered, Martin says, whether building a trail on Nisenan ancestral land or talking to the public about the genocide during the gold rush.

“It’s our people’s job to say, ‘This really happened,’” she says. And it’s the responsibility of groups such as hers to do the legwork on projects like the trail, but the tribe “gets to decide what goes on it.” She sees her organization’s job as “the red-tape cutters. That’s an easier mission statement than, ‘I’m going to save the Indians.’ Because we save each other.”

As for Covert, she continues to pursue reinstatement of federal recognition for her tribe, more than five decades after it was snatched away. Although UnderCover’s live shows have stopped for now, she still sings and writes songs, often in her Nisenan language, with lyrics inspired by the landscape to which her culture is intrinsically tied:

Yo yo yo

(Flower, flower, flower)

Payo u’koype

(Let’s all go dance)

Yomenim k’aw hededi

(Springtime is here)

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Fighting for Recognition

Nevada City Rancheria spokesperson Shelly Covert on recovering land and federal status for the Nisenan Tribe

Comstock’s spoke to Covert — who was born and raised in Grass Valley — about her work with the Nisenan Tribe and why it matters.

How Cornish Pasties Got to California

Grass Valley’s Cornish pasties are a remnant of the town’s mining history

Cornish pasties are an edible trace of the gold rush, connecting

Grass Valley to a global history of migration and

extraction.

Laying the Groundwork

A widespread effort to achieve environmental justice in Sacramento is gaining momentum

Proponents say environmental justice efforts will only be successful if they are inclusive and equitable.

Shouldering the Burden

Progressive-minded farmers in the Capital Region undertake steps to battle and adapt to climate change

A growing movement of farmers is focused on agricultural practices that can mitigate or adapt to an uncertain future brought by climate change.

Part of this month’s Innovation issue

Comments

Wow...very thorough article, great information, good stories and a little mantra to think of. Bless you all for your work.