In July 1995, Pamela Eibeck took one of those less-traveled roads that would lead to a career she hadn’t imagined.

A few years earlier, she’d been a tenured associate professor of engineering at UC Berkeley, and her husband, William Jeffery, was a corporate attorney. They had four children, all under age 12 — including a toddler and infant born 18 months apart.

Tired eyes? You can listen to the audio version of this article here:

One evening, Eibeck was home trying to get dinner together while Jeffery was ferrying their two older boys to soccer practice. It had been a long day at work and a tiring commute from Berkeley to Palo Alto where they lived.

Suddenly, Eibeck says it hit her: She couldn’t do it all. She slid to the floor and started crying. “This is insane,” she thought.

She picked herself up and kept moving, but she and Jeffery discussed a change to make space for a more balanced life. And in 1995, they did the almost-unthinkable, giving up prestigious jobs and Eibeck’s tenure at a major university to move to Flagstaff, Ariz. Eibeck took a position at Northern Arizona University as chair and professor in the department of mechanical engineering. Moving away from a larger city dialed down their pace and stress, and the family started spending more time together biking, skiing and exploring.

One day in her new job, a vice president told her, “You think different. You think like a president.” He encouraged her to get on a track toward a top position in administration. University leadership was not on Eibeck’s shortlist of life goals. But she took him up on it, and he sent her to leadership programs and gave her leadership assignments. She started believing she could be a good administrator.

That led in 2004 to a job as dean of engineering at Texas Tech University. It made her one of only a handful of female engineering deans in the country. Five years later, she was appointed president at the University of the Pacific, where she is today.

That experience is part of why Eibeck thinks the career paths of women and minorities are more likely to be nontraditional. In academia, they’re less likely to follow a straight line of promotions toward full professor or department chair. They often broaden their research focus by working in interdisciplinary areas outside their specialties.

She believes those alternate paths can make for more creative thinking. And it’s why today she encourages Pacific’s search committees to be open to nontraditional resumes and career trajectories as they identify job candidates.

That’s a lesson in how diversity at the top opens up the hiring pipeline to good candidates who routinely get passed over. Across the country, women are still dramatically underrepresented as university leaders. But two California systems are showing other universities how they can broaden who gets considered for top roles.

Leadership Diversity Is Good for Schools

In the last 50 years, higher education’s customer base has become decidedly more female. In 1967, 40 percent of college students were women. By 2014, it was 56 percent. The U.S. Department of Education projects that will climb to 59 percent by 2025.

But the people responsible for delivering those educations are still overwhelmingly male. A 2015 study found that just over 1 in 4 college presidents were women. Data from the 2013-2014 school year show that a little over a third of chief academic officers are women. Fewer than 1 in 3 college board members and fewer than 1 in 5 board chairs are female.

It’s not as though women in academia haven’t earned the right to leadership roles. In the 2010-2011 school year, women researchers pulled in 56 percent of the top federal research grants in education, health, humanities and science. That’s despite making up only 30 percent of tenure-track faculty, according to a 2013 report by the Colorado Women’s College at the University of Denver.

Beyond fundamental fairness, all of that matters because there’s now a body of research suggesting that leadership diversity makes for better decisions. For example, a study last December by investment consulting firm MSCI found that companies with at least three women on their corporate boards enjoyed higher returns on equity than those with fewer than three. “The real power of diversity is that you get better ideas in play, more people touch them and more people own them,” says Timothy White, chancellor of the California State University system.

There’s Another Way

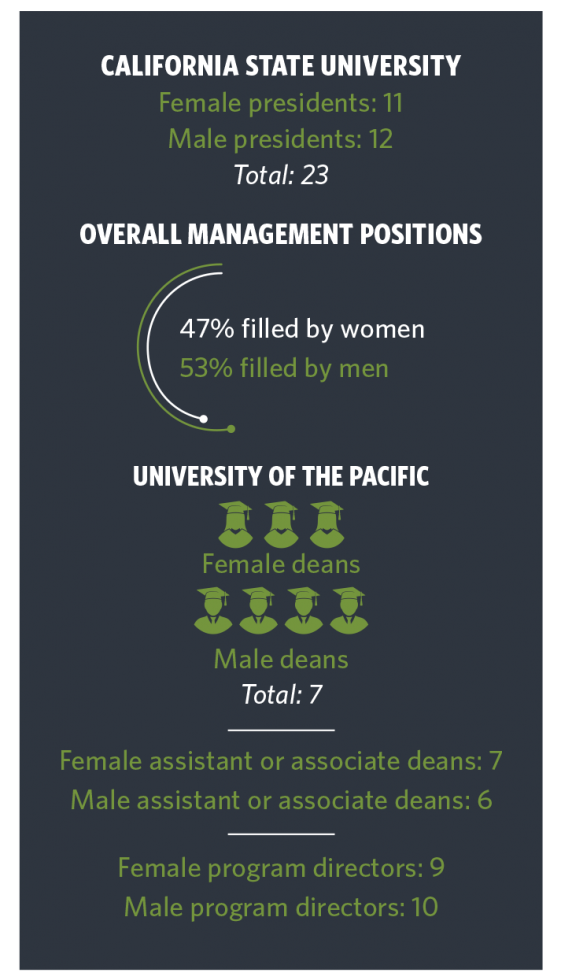

That’s not just talk — the CSU system now may well lead the nation in the proportion of women serving as campus presidents in a public university system. With new hires in the last year, 11 of 23 CSU campuses have female presidents, which has made news nationally. Overall, about 47 percent of CSU management positions are filled by women.

Locally, the University of the Pacific has done something similar — its leadership reflects its student population, which is 52 percent female. In 2009, the university hired Eibeck as its 24th president, but there’s gender parity up and down the organizational chart. Among their deans are three women and four men. Seven women and six men hold assistant or associate dean positions, and the program directors comprise nine women and 10 men. The board of regents is composed of 40 percent women (10 percent higher than the national average), and the board is chaired by a woman.

Those numbers aren’t accidental. Both systems deliberately aimed to diversify and set up processes to make it happen. Neither school says openly that they’ve made a shift toward more gender parity in recent years. But the gender gains among CSU system presidents have all happened since 2010, when only 4 of 23 presidents were women. And a Pacific spokesperson says the school has a “long tradition of valuing gender parity” but calls Eibeck’s 2009 hiring perhaps the school’s “most recent and significant” move toward equal representation in leadership.

So at both CSU and Pacific, they’ve shaken up their search committees. Schools can talk about diversity, but it’s these committees, usually composed of faculty, that make it happen. That group usually helps identify sources of recruitment, writes job ads and whittles a pile of resumes down to a manageable number.

The makeup of those committees can drive who gets hired. “You bring in a bunch of folks who are all of the same gender, the same race and ethnicity, the same set of experiences, they’re going to identify some great candidates, but they’re going to look like that search committee,” White says. So diversity is a key criteria that CSU departments use in picking members for those committees.

The classic study showing that demographics matter in hiring is what’s happened to U.S. symphony orchestras. When orchestras began using blind auditions in the 1970s, with applicants playing behind a screen, the percentage of female players jumped from less than 5 percent to about 25 percent.

Both schools also require search committees to recruit for diversity. At Pacific, search committee members undergo bias awareness training arranged by the school’s assistant provost for diversity. At the beginning of the search process, committees also create a diversity recruitment plan that they use to guide where to advertise, how to use personal networks to publicize the position and which professional organizations to contact about the job.

On CSU campuses, dedicated equity and diversity offices or diversity officers work with search committees and human resources departments to ensure a representative hiring pool. For example, they review job announcements and recruitment plans and offer suggestions for broadening the candidate makeup. White says CSU’s recruitment process has been “intentional and purposeful, and the process was designed to lead to a diverse pool of finalists. And then you let everything go and pick the best person. That’s how you do it.”

White says the CSUs also seed the job pipeline — lower-level positions like assistant department chair — with qualified women and minorities. Some people blossom in those leadership roles and work their way up the academic leadership ladder.

Take Ellen Junn, one of the 11 female CSU presidents and now head of Stanislaus State. She started as an assistant psychology professor at San Bernardino State in 1991. While teaching, she was asked to coordinate an educational equity and faculty mentoring program, then became acting head of a department. She’s since moved steadily up the ranks at five CSU campuses: director of a faculty development center, associate dean, associate provost, chief academic officer, provost and now president, launching new campus initiatives in every role. At Stanislaus, she’s shattered what she’s called the “bamboo ceiling” as a Korean-American female university president.

Branching Out Gets Easier

Schools that broaden their leadership hires appear to create a kind of snowball effect. Eibeck says that once there were women in Pacific’s president, board chair and provost positions, more women started applying for leadership roles. She believes women are more apt to apply for leadership roles when they see other women in management positions. “I think it gives them more confidence that they’ll be treated with respect and as an equal player,” she says.

A fair bit of research actually backs up that insight. A study last year by the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute concluded that a female university president who stays in her job for 10 years may increase the share of female full-time tenured and tenure-track faculty in the humanities by 36 percentage points. Similarly, a 2009 study found that institutions with female presidents, female provosts or academic vice presidents, and a larger share of women on their board of trustees had larger increases than other schools in their share of female faculty members during the study period of 1984 to 2007. And a 2009 National Research Council study found that more women applied for positions in a science, technology, engineering and math department if the head of the search committee was a woman or there were more women on the search committee.

There’s another practical way that having more women as academic leaders could help younger colleagues: They may be more open to flexible work arrangements -— because they’re more often denied it than their male colleagues. A 2013 Journal of Social Issues study reported that women were less likely than men to get flex-time when they asked for it.

“I think we’re still structuring work in very antiquated ways during a time when the technology gives us the capacity for flexibility,” says Lynn Gangone of the American Council on Education. Her organization runs Moving the Needle, an initiative whose goal is to have half of college presidencies held by women by 2030. “I think you’ve got a lot of younger faculty looking to move up the ranks and still have families,” she says. “It doesn’t have to be either/or.”

More broadly, female academic leaders may help redefine what leadership means. We now have more examples of women who are tough, direct, strategic leaders who also have a warm interpersonal style, says Junn. “Having 11 women presidents,” adds Chico State president Gayle Hutchinson, “is a signal to young girls that they can be a president too.”