People love to hate school lunch. But the Nutrition Services team at Sacramento City Unified School District is out to change that. In November, the district will complete construction of its 50,000-square-foot Central Kitchen. Once the district is able to reopen campuses (a timeline that remains unknown), the kitchen will open with a staff of 30-40 full-time employees to cook from scratch meals like lasagna, vegetable soup, street tacos, muffins and loaves of bread that will replace the majority of frozen and reheated processed entrees. Those meals will be delivered to 81 schools served by the district.

The Central Kitchen will feature a large bakery, a temperature-controlled meat-processing room, a produce-processing room and 15,000 square feet of office space, says Diana Flores, director of Nutrition Services for the district. It’s the next big step in locally overhauling a behemoth of a federal program with strict regulations, a tight budget and a lack of infrastructure.

The district’s efforts to transform school lunch began more than 10 years ago with a question, Flores says: Was the district serious about wanting better food for its children? That led to restructuring its operating model to accommodate greater control and better nutrition while still working within the confines of the federally funded National School Lunch Program.

The lunch program, established in 1946 under President Harry S. Truman to provide nutritious, low-cost meals to students, expanded under the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the 1960s as a means to provide farmers with a market for surplus crops they couldn’t sell. Then it grew even larger, becoming deeply rooted with big food processors like Tyson Foods and Don Lee Farms. Today, school lunch is big business, costing $13.8 billion annually, and serving nearly 30 million students a day and almost 5 billion meals annually nationwide, according to the USDA.

SCUSD’s Nutrition Services serves 43,000 meals a day during the normal school year, with 80 percent of its 47,900 students qualifying for free or reduced-price meals, says Flores. In a school district with a population that experiences high food insecurity, food deserts and obesity rates for middle schoolers nearly double the U.S. average of 18.5 percent, according to Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health. Nutrition in school matters.

Related: Keeping It in the Community

And demand for meals skyrocketed when SCUSD closed schools on March 16 in response to the coronavirus pandemic. The USDA quickly shifted to the Summer Food Service Program, which allows anyone 18 and under a free meal regardless of need or where they attend school. By mid-June, two months after schools closed, SCUSD had served 2 million meals (breakfast and lunch). For comparison, the district served 84,641 meals in the summer of 2019.

“We know all too well that these meals are some of the only meals (students are going) to get during the day,” says Kelsey Nederveld, a nutrition specialist with SCUSD.

Nationwide, serving nutritious food children liked became significantly more challenging when the USDA radically altered school nutrition programs in the 1980s, designating them as self-funded programs, cutting off direct access to a district’s general fund to cover operating expenses. Budgets for nutrition programs became dependent upon reimbursement from the USDA (and the state when funds were available) for meals served. To align with the change in funding, school kitchens shrank, modeling a heat-and-serve capacity without the space or equipment to perform basic functions, such as washing and preparing fresh produce or assembling sandwiches.

Lobbying for Funding Changes

That’s where the USDA’s federal commodity program, Foods in Schools, comes in. Each district is allotted an allowance to purchase food through the USDA’s program, based on the number of meals served the previous year, says Flores. SCUSD received a credit of $1.9 million for the 2019-20 school year, approximately 17 percent of the $8 million to $9 million it spends on food each year.

While the program offers fresh and processed proteins, grains, produce and fruits, most districts use their allowance to purchase animal proteins because they’re expensive, says Flores. Without the space to store or cook with raw ingredients, most districts are limited to purchasing processed and frozen items, like chicken nuggets and hamburger patties that can be heated and served, she explains.

“We’re building a (central) kitchen, and we don’t necessarily want processed products. We want to cook it ourselves. If we were to receive a check, we would go out and bid and get the best price for all our products. If we want to buy local, we could. If we want to buy California, we could.”

DIANA FLORES DIRECTOR OF NUTRITION SERVICES, SACRAMENTO CITY UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT

But Flores says SCUSD can purchase differently and wants cash in lieu of commodity dollars. In 2008, under Flores’ supervision, her department began converting a 50,000-square-foot district warehouse for food storage. With grant funds, she directed the installation of commercial refrigeration and freezer systems — both large enough to house several semitrucks worth of food — and she grew her fleet of refrigerated food trucks from two to 11. That meant she could cut out food distributors — and their markups, which can be as high as 25 percent of the food cost — and use cash funds in her budget to purchase directly from food manufacturers.

“We’re building a (central) kitchen, and we don’t necessarily want processed products. We want to cook it ourselves,” says Flores. “If we were to receive a check, we would go out and bid and get the best price for all our products. If we want to buy local, we could. If we want to buy California, we could.”

That could mean big savings too. Last year, Nederveld lobbied in Washington, D.C., for local sourcing and food procurement as part of the Sacramento Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce Capitol-to-Capitol program’s food and ag team, paid for by Nutrition Services (no district funds were used to pay for this event). She had the opportunity to show the savings cash in lieu could provide.

“I pulled six or seven items off the commodity list … strawberries, broccoli florets, baby carrots, chopped romaine. Things in our meal program now … (that) we buy direct from the manufacturer or the grower,” says Nederveld. “The savings of us procuring without USDA on cost alone is $270,000. Those aren’t even high-volume items. The commodity program is great for districts that don’t have the resources that we do in California.” The state has more than 69,000 farmers that generate $50 billion annually in sales, yielding more than 13 percent of all U.S. agriculture, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

In order to replace SCUSD’s federal commodity allowance with cash, a new law must be passed. While Nederveld has been working with various members of Congress, discussions are currently on hold due to the pandemic.

In the meantime, Flores and her team are talking with companies who provide USDA commodity foods, to discuss options to purchase more raw ingredients, like chicken, instead of processed, frozen products like nuggets. “If (we) process it ourselves, it’s going to taste better for one, I know, and it’s fresher, and it won’t have sat in a frozen box somewhere for six months, and we can control ingredients,” says Flores.

Thomas Lucero, a former corporate chef at two Sacramento

restaurants, manages the Sacramento City Unified School

District’s new Central Kitchen that will have a staff of 30-40

full-time employees.

Balanced Meals, Balanced Budgets

Staff at SCUSD middle and high schools already cook with raw ingredients like chicken (purchased through a distributor) and ground beef (available as a USDA commodity food), says Nederveld. To accommodate larger student bodies at secondary schools, kitchen facilities are larger and have sufficient staff. While facilities are aging, Nederveld says upgrades have been made to equipment to support more cooking from scratch. About 60 percent of the menu at high schools are cooked from scratch, says Flores.

Spring 2020 lunch menus from the district’s comprehensive high schools included no fewer than six lunch options each day, featuring entrees such as a Mediterranean wrap, chicken Alfredo pasta, southwest chicken salad, and a fruit and yogurt protein box. There also was chili cheese nachos, a bacon cheeseburger with Tater Tots and Wild Mike’s Ultimate Pizza.

“I visited Hiram Johnson High School, and I was just watching service at lunch, and I literally got emotional,” says Flores. “I was stunned how they just will stand in line, these huge lines for food. They love the food.” That day, students were in line for the Chipotle-style burrito bowls customized to order.

But they haven’t experienced the same success at the district’s 60 elementary schools. “We just hit a brick wall when it came to the elementary schools. We could not duplicate the same menu there,” says Flores. “They have tiny kitchens, and a school with 300 students (has) two staff members. One’s there for six hours, the other’s there for three hours.”

They have added fresh salad bars to the elementary schools, featuring selections such as fresh spinach, blueberries and mangoes, says Nederveld.

The majority of the district’s meals feature animal protein. Reimbursable meals must meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which still recommend dairy products, seafood, lean meats, poultry and eggs, even though study after study continues to show a correlation between animal protein and diseases such as cancer, obesity and heart disease. Flores says the new Central Kitchen will accommodate more vegetarian — and vegan — options.

But selling meals, whatever they are, determines the budget. Revenue from federal and state reimbursements plus income from meals purchased at full price, funds the majority of SCUSD Nutrition Services’ $30 million annual budget. The department receives $3.67 from the USDA for every free lunch served and roughly 20 cents from the state of California until funds run out, which may be as early as February or March each year, says Flores. Full price lunches bring in $2.75 at elementary schools and $3.25 at the middle and high schools.

Since it receives no support from the district’s general fund, Flores says revenue must cover labor; benefits for staff; supplies; refrigerated food trucks (each costs $130,000); repairs for the trucks; fuel; forklifts for the warehouse; equipment and repairs for school kitchens; miscellaneous operating expenses; and a fee paid back to the district that averages between $700,000 and $1 million annually to use the district’s payroll processor, human resources and accounting departments. Oh, and food.

“When everybody says, ‘Why don’t they serve better lunches?’ Out of that ($3.67), my budget for food is $1,” says Flores.

But SCUSD Nutrition Services’ budget has remained in the black for the last 16 years. Flores has maintained that since 2008, because of the way she purchases. According to a study by the USDA released in April 2019, School Nutrition and Meal Cost Study, the majority of school nutrition programs operate at a deficit.

Funds to build the Central Kitchen, managed by Thomas Lucero, the former corporate chef at local restaurants Land Ocean and Sienna, came from Measure R, approved by Sacramento voters in 2012, granting $68 million in bond funds to improve health and safety for children in SCUSD, including upgrading kitchen facilities for improved nutrition.

Locally Grown — and Healthier

While the Central Kitchen marks significant progress toward improved school nutrition, success is also a measure of whether the students enjoy and consume the food. That’s where the National Farm to School Network, run by the California Department of Food and Agriculture, comes in.

While the program ensures farmers have access to the school market, it also expands children’s access to fresh food, says Nicholas Anicich, the lead for the California Farm to School Program. “People just think of (farm to school) as … purchasing local, but it’s also about access and education,” says Anicich. “You have to buy it local, you have to educate the kids and let them experience it in order to get them to eat it regularly.”

That’s the vision the program is working to broaden, he says, and SCUSD models that vision well. Through a long-term partnership with local nonprofits Food Literacy Center and Soil Born Farms, students in select elementary schools are immersed in healthy-eating programs that link classroom education to the cafeteria and experiential learning.

“We partner on a vegetable of the month, and we cook with it in food-literacy class (with the students), Soil Born is either planting (or) harvesting it (in school gardens), the Health Education Council is talking to parents about it and at those particular schools, they’re putting it on the salad bar,” says Amber Stott, founder and CEO of the Sacramento-based Food Literacy Center. “Most of the kids we (work with) in schools have a very narrow experience of fruits and vegetables. It might be apples, oranges and lettuce. We get kids who’ve never seen broccoli or pears before.”

But after years of working with students, the culture of healthy, fresh food is baked into these schools, and children become huge food adventurers, she says. “The kids really understand more about their health and how their food affects their health,” Stott says.

SCUSD sources fresh ingredients from more than 35 farms throughout California and plans to work with the National Farm to School Network to identify additional farmers to meet their growing needs. “(At least) half of our product comes from local farmers (those within 250 miles) in season,” says Flores. That figure is expected to increase to as much as 80-90 percent when the Central Kitchen opens.

While many small farms can’t meet the volume of produce needed by school districts like SCUSD, Nederveld says the district hopes to work with local growers to scale production to meet the majority of its need for in-season local produce like tomatoes.

California’s rebalanced budget, necessitated by the recession caused by the coronavirus pandemic, includes $10 million to expand California’s Farm to School Program. “Some of our kids are eating four meals a day with us,” says Nederveld. “If that’s the case, then we need to make sure they’re well-nourished. … (But) if they’re not going to eat it, what have we done?”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Keeping It in the Community

Grassroots efforts feed some of SCUSD’s most vulnerable families during the pandemic

After the closing of smaller food distribution centers that couldn’t meet COVID-19 required regulations, a grassroots program formed to serve people in need.

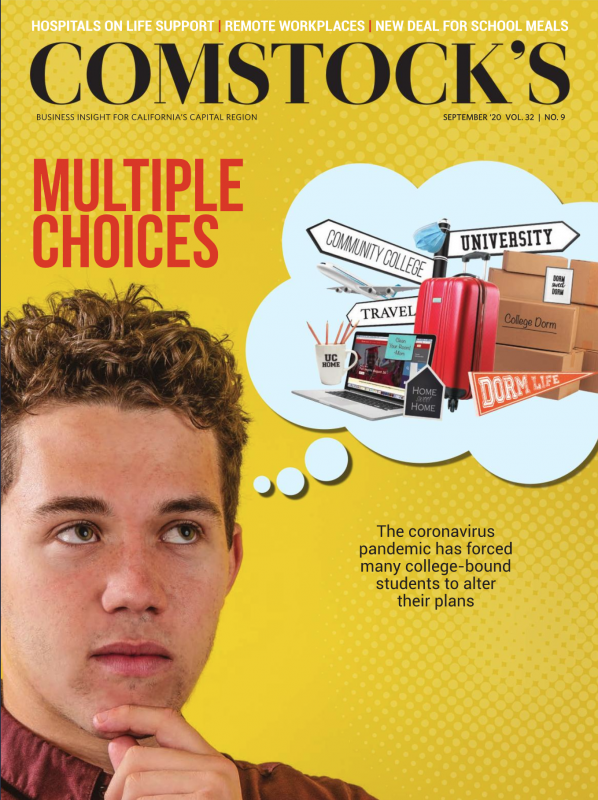

Virtual Variations

With the coronavirus pandemic forcing most college classes online, recent high school graduates are finding their choices have changed

Students are weighing all the options, including attending community college, learning online or postponing college altogether.

Appetite for Equity

Black-owned restaurants rely on community support to endure the pandemic and racial inequity

The community has begun to increase its support of Black-owned restaurants due to the heightened awareness of the inequities Black businesses face, but will it last?

A Double-Edged Service

Third-party delivery services help — and hinder — restaurants during COVID-19

The commission delivery companies take per order, a range between 20-40 percent, has many wondering if these services are taking advantage of an unfortunate situation.