In 1904, on the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase, St. Louis hosted 19 million people at the largest World’s Fair in history. From across the globe, cities sent delegations to showcase their assets, including new whiz-bang technologies like the X-ray, fax machine and something called an ice cream cone.

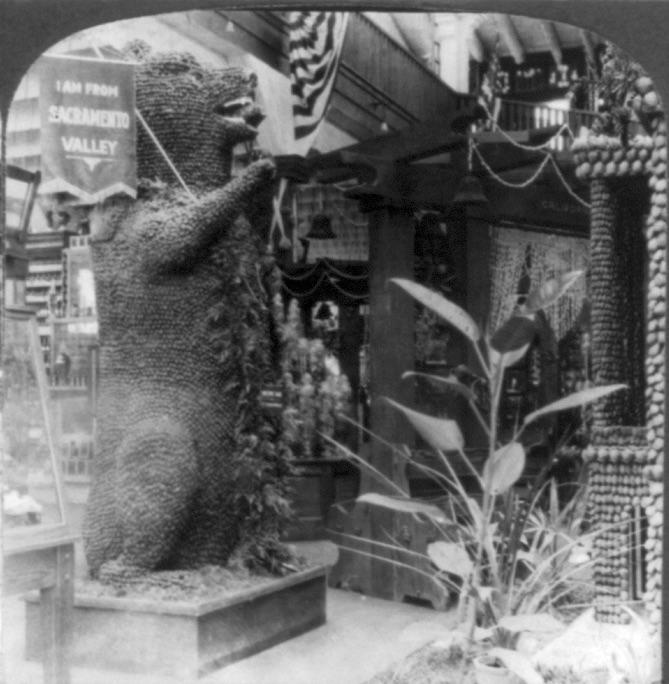

Sacramento sent a giant “Prune Bear.”

The creature was a life-size grizzly bear — made from prunes. The eyes lit up in an early use of electricity. The “Prune Bear” could roar, thanks to a gramophone hidden in its jaw.

“This was a multimedia bear,” says Sacramento historian William Burg, author of the upcoming book “Wicked Sacramento,” chuckling a bit. “It was meant to show off the brand of the region’s agriculture.” Burg says Sacramento marketing reps held a contest in which people guessed how many prunes it took to make the bear, and the winners walked away with a box of prunes. The reps passed out brochures touting the merits of prunes, Sacramento and its agricultural bounty.

Sacramento has struggled with its branding for more than a century, eager to shed the image of “near San Francisco, but cheaper.” Over the years, Sacramento has been the River City, the Indomitable City, the Emerald City, the City of Trees and the Camellia Capital. More recently, the farm-to-fork movement has raised awareness of the local food scene, but as the region also tries to highlight its growth in business, tech, art and culture, a new brand is in the pipeline — spearheaded by a yearlong effort from Visit Sacramento — suggesting that Sacramento is more than farms or food or any one thing: that Sacramento is unstoppable.

As for whether Sacramento needs another brand, that might depend on what it has to offer. Burg is skeptical that the “Prune Bear” was any sort of impetus for agriculture investment in the region. “The branding did not produce the agricultural regions of California — the agriculture drove the brand,” says Burg. Though if you ask around, agriculture just scratches the surface.

Sacramento sent a giant “Prune Bear” to the World’s Fair in St.

Louis in 1904. It was a life-size grizzly bear made from prunes.

Its eyes lit up, and it roared. “It was meant to show off the

brand of the region’s agriculture,” says historian William Burg.

(Public domain photo)

Who starts the branding process? “Typically, the drive to create a city brand will come from the city government,” says Malcolm Allan, president of the London-based branding firm Bloom Consulting, which has worked on city branding for clients such as Abu Dhabi, Stockholm, Helsinki and Madrid.

Yet the closest thing that the Sacramento city government has to a brand manager is Carlos Eliason, in the Office of the City Manager, whose working title is creative specialist. He’s responsible for, as he explains it, “the high-level storytelling and branding for the city, which involves photos, graphics, video, communications, social media — I’m pretty much a catchall.”

On a micro level, Eliason has a strong sense of the city government’s brands in terms of things like fonts and logos and color palettes. Yet on a macro level, no entity in the government gives direction on Sacramento’s larger cultural brand. “There’s no singular bit of messaging — no program — that says, ‘Here’s overall Sacramento.’ Right now everyone is working toward this big wave of, ‘Sacramento is cool. Sacramento is this new place to be,’” he says. But who spearheads the messaging? “That’s kind of up in the air,” Eliason says.

Visit Sacramento has tried to fill that role, leading the transition to America’s Farm-to-Fork Capital. In March 2017, Visit Sacramento painted the city’s water tower welcome, removing “City of Trees” and replacing it with “America’s Farm-to-Fork Capital.” Not everyone loved it. “People lost their minds,” says Mike Testa, the CEO of Visit Sacramento. “I had people calling me, threatening me and saying, ‘What are you doing? That’s been our identity! How can you change this?’” Testa says.

“City of Trees,” painted on the water tower in 2006, is a lovely phrase. But despite Sacramento’s tree bona fides (an MIT project called Treepedia, launched in 2016, measures cities’ canopy coverage or Green View Index and ranked Sacramento as second in the nation and seventh in the world), there remains a problem: Minneapolis; Ann Arbor, Mich.; Charlotte, N.C.; and Buenos Aires, Argentina, also call themselves the City of Trees. In fact, there are 30 cities of trees. “From a marketing standpoint, when you share an identity with 29 other cities, that doesn’t do it justice,” says Testa.

The other problem with “City of Trees” is that it didn’t consist of much beyond the slogan. “City brand strategy is not about logos and taglines,” cautions Allan. He says that for a brand to really stick, it needs larger buy-in. “Typically, a brand strategy developed without the active involvement — and financial support — from the private and community sectors will fail,” he says.

To that point, “Farm-to-Fork” was created with a partnership from the private sector, starting with the name, suggested in 2012 by Josh Nelson of the Selland Family Restaurant Group, and included both a steering committee and a culinary committee of chefs. What does Sacramento do better than anyone else? “We produce 80 percent of the nation’s caviar. We produce 99 percent of the country’s sushi rice. (And) 96 percent of the world’s processed tomatoes come from within 250 miles of Sacramento,” says Testa, rattling off the stats from memory. “When we started diving into the research, we could claim that our food production is bigger than anyone else.”

Eighty percent of Visit Sacramento’s funding comes from the private sector. It partners with Valley Vision (a regional think tank that conducts research and nudges policy) and works with local restaurants to slap the farm-to-fork logo on their menus. When the Sacramento Kings play a nationally televised game, Visit Sacramento sends gift baskets — filled with local wine and food — to the commentators’ hotel rooms. Testa says the strategy has paid off, pointing to Bill Walton’s on-air mention about “how great Sacramento is — from the weather, to the food, to the people.”

Testa works with a New York public relations company, the Lou Hammond Agency, to book national media. It sends writers and editors to Sacramento to cover foodie events like the Farm-to-Fork Festival and Tower Bridge Dinner, which led to coverage like a gushing piece in New York magazine that praises Sacramento’s “red-hot craft-beer scene” and how the city has “upped its art game in a big way” and is “brimming with a creative, DIY culture and the enterprising types who feed it.”

“People lost their minds. I had people calling me, threatening me and saying, ‘What are you doing? That’s been our identity! How can you change this?’” — Mike Testa, CEO, Visit Sacramento

Contrast farm-to-fork with a 2014 grassroots effort called the Sacramento Region Brandathon, a volunteer-led effort that brought together hundreds of marketing reps, professionals, city staff and councilmembers, and enthusiastic Sacramentans to whip up a new slogan for the city. During a series of brainstorming sessions, the teams mulled over taglines like “You belong here,” “Live. Work. Play,” “Here. We. Grow,” and the winning finalist with 46 percent of the vote: “In Season.”

The Brandathon was an inspired display of civic pride, but without any real backing from the city or private sector, the slogan died on the vine. Testa says the Brandathon brought the community together and sparked good discussion, but it lacked a lead organization to spur next steps, and “at the end of the day, it is difficult to do marketing by committee.”

‘Nothing in the Way’

At least one local economic developer wants to see Sacramento go beyond food. Barry Broome, CEO of the Greater Sacramento Economic Council (an organization with a $4.1 million budget to draw businesses and economic growth to the city), hopes to see Visit Sacramento help elevate the profile of economic assets the way it’s helped agriculture players.

“We are moving from a sleepy government town to a more sophisticated value proposition that revolves around access to highly skilled talent, a robust university system, and a region that boasts a great quality of life and cost of living,” Broome says.

Yet cramming all of that in one concept is tricky. “Sacramento, like many other cities around the nation, struggles with landing on one identity,” Broome admits.

Visit Sacramento is taking a stab at this, and a new brand identity is in the pipeline. The gist of it: “Nothing in the way.” It’s a working title, what Testa calls the “internal rudder” for thinking about the city’s identity. It’s been at it for a year — collaborating with groups like GSEC, Downtown Partnership, Visit California and Midtown Association — and is working on creative visuals, copy and a specific marketing plan. Testa expects this to take a few months.

Take our poll: What brand would you pick for Sacramento?

“People in Sacramento don’t let things stop them,” Testa says. When the Kings’ relocation to Anaheim was considered a fete accompli, he points out the city rallied and saved the team. He was told Sacramento would never be featured in a Michelin Guide. This year, it is. (Visit California paid Michelin $600,000 to include regions throughout the state, although Testa insists Sacramento earned its foodie merit.) Organizers were told the Aftershock Festival could never be a major music event; this year they’re expecting a crowd of 90,000. “Sacramentans are very humble,” Testa says. “They don’t crave the attention of other cities. Instead, they say, ‘Tell us no, and we’re going to figure out how to do it.’”

This is an appealing mindset, but it’s a little fuzzy how it translates into a clear brand. Farm-to-fork is easy to visualize — a plump tomato, a juicy peach. It’s specific, it’s concrete, and it’s unique to Sacramento. Yet people in cities across America, no doubt, think that they’re good at overcoming obstacles (just as there are 30 “City of Trees”).

Testa clarifies the new brand will not replace Farm-to-Fork — “that’s here to stay” — but will be a supplement. He points to Austin, Texas, as an example of this framework. “Austin is the live-music capital of the world, but there are so many great things in Austin besides the music,” he says. “The music is a hook. Can we use food as a hook?” Come for the food, stay for the art, the tech, the innovation, the cultural diversity.

Spreading the Message

The truest test of a city’s brand is if those outside the region are aware of it. The evidence is mixed. A Google search for Sacramento and “farm-to-fork” fails to yield the city in a national publication on the first page of results. Google trends for Sacramento have hardly budged in the past 15 years. Then again, Thrillist raved, “Why Sacramento Is the Best Up-and-Coming Food City in America” and WalletHub named Sacramento one of the 16th on its list of the “best foodie cities in America.” Bon Appétit featured Sacramento’s food scene in 2017.

Sacramento food is creeping onto the national radar, but what about the idea that it’s a great place to do business? In 2018, GSEC conducted a national survey of “site selectors” — the crucial advisers who help decide where companies should locate their offices — and asked them if, in the last three years, Sacramento even made their list of top 10 destinations for companies. Less than half (47 percent) said yes. Of those who even considered Sacramento in their top 10, only 12 percent actually chose the region. There’s work to be done.

Here’s one final perspective: This is tough to define with sharp edges, but Eliason observes that cities like Denver, Seattle, and Portland, Ore., have what he calls a “specific flavor.” (Denver, for example: “ruggedly laid back with roots in confidence,” “powerful but light and open,” “kinetic but calm.”) And now, thanks to a decade of what many in the region feel to be a renaissance of business and culture, Sacramento is developing its own specific flavor.

Eliason pauses to think before trying to describe it.

“If I can take off the government suit for a second, it would almost be like you wake up, and you smell the fresh morning air, and there’s dew in the grass,” he says. “There’s a freshness. It hits your senses. Sacramento is doing that lately. We’ve been hitting a lot of people’s senses, whether it’s sight, sound or taste. We’re activating those stimuli. People are rediscovering their senses here.”

And if that fails, there’s always prunes.

Recommended For You

To Build Authentic Brand Equity, You Must First Build The Culture You Want

Change your brand from the inside out

Your brand is an extension of your corporate culture

From Pond to Fork

Passmore Ranch serves locally-raised seafood to some of the Capital Region’s finest chefs

Passmore Ranch invites local chefs to swim for their fish.

Capital Region Schools Get Their Own Farmers Markets

In San Joaquin County, elementary and middle school students are running farmers markets at 10 after-school sites. In Yolo County, the Yolo Food Bank runs each market held at local schools, but hundreds of students get to shop weekly for fresh produce. And in Sacramento County, a hybrid approach currently serves five schools.